You’ve probably heard about the icy chunks floating around beyond Mars. That’s the asteroid belt. However, there’s something far more intriguing lurking in the shadows of our solar system’s outer reaches. The Kuiper Belt is a circumstellar disc in the outer Solar System, extending from the orbit of Neptune at 30 astronomical units (AU) to approximately 50 AU from the Sun. This frozen frontier holds secrets that could reshape our understanding of how planets formed and what lies in the darkness beyond.

Imagine a region twenty times wider than the asteroid belt and up to two hundred times more massive. Objects in the Kuiper Belt are presumed to be remnants from the formation of the solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. Unlike the rocky debris between Mars and Jupiter, these ancient wanderers carry the frozen memories of our cosmic birth. So let’s explore this mysterious realm where dwarf planets dance in eternal twilight and where humanity has only just begun to peek behind the curtain of deep space.

A Discovery Decades in the Making

The story of the Kuiper Belt reads like a cosmic detective novel spanning nearly a century. The first astronomer to suggest the existence of a trans-Neptunian population was Frederick C. Leonard. Soon after Pluto’s discovery by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930, Leonard pondered whether it was “likely that in Pluto there has come to light the first of a series of ultra-Neptunian bodies”

Astronomer Kenneth Edgeworth suggests that a reservoir of comets and larger bodies resides beyond the planets in 1943. Astronomer Gerard Kuiper predicts the existence of a belt of icy objects just beyond the orbit of Neptune in 1951. After five years of searching, astronomers David Jewitt and Jane Luu discover the first KBO, 1992QB1 in 1992. However, the hunt for actual proof took another four decades of patient searching with increasingly powerful telescopes.

Experimental evidence of the Kuiper Belt came with the 1992 discovery by Jane Luu and David Jewitt of object 1992 QB1. This tiny, distant world became the smoking gun that confirmed what theorists had long suspected. The discovery unleashed a flood of similar finds, revealing that Pluto wasn’t alone in its distant orbit after all.

The Frozen Chemistry of Deep Space

Step into the Kuiper Belt and you enter a realm where the Sun’s warmth barely registers. While many asteroids are composed primarily of rock and metal, most Kuiper belt objects are composed largely of frozen volatiles (termed “ices”), such as methane, ammonia, and water. These aren’t the familiar ices from your freezer though. They’re exotic chemical cocktails that tell the story of our solar system’s earliest days.

KBOs must be largely water ice along with ice, carbon monoxide ice, methane ice, methanol ice, ammonia ice, amorphous (noncrystalline) carbon, silicates and other stony materials, sodium, carbonates, simple hydrocarbons, and clays. The larger objects harbor the most volatile materials on their surfaces. The largest KBOs, such as Pluto and Quaoar, have surfaces rich in volatile compounds such as methane, nitrogen and carbon monoxide

Think of these worlds as cosmic time capsules. These icy bodies are believed to be remnants from the early solar system and have remained relatively unchanged since their formation billions of years ago. Each contains pristine samples of the materials that swirled around our young Sun when Earth was nothing more than colliding dust particles.

A Population Beyond Imagination

The numbers alone are staggering. NASA says there may be trillions of icy objects in the Kuiper Belt, with hundreds of thousands of these objects having diameters larger than 62 miles (100 km). Yet what we’ve catalogued represents only the tiniest fraction of what’s actually out there. Since its discovery, the number of known KBOs has increased to thousands, and more than 100000 KBOs over 100 km (62 mi) in diameter are thought to exist.

So far, more than 2,000 trans-Neptunian objects have been cataloged by observers, representing only a tiny fraction of the total number of objects scientists think are out there. In fact, astronomers estimate there are hundreds of thousands of objects in the region that are larger than 60 miles (100 kilometers) wide or larger. These distant worlds come in all shapes and sizes, from tiny pebbles to dwarf planets larger than some of our solar system’s moons.

Many of these objects aren’t traveling alone either. Around 80 KBOs have been discovered to have binary companions of similar sizes meaning it can’t be accurately determined which is the main body and which is the moon, these are referred to as “binary KBOs.” It’s like a cosmic dance happening in slow motion across billions of miles.

The Dwarf Planet Kingdom

The Kuiper Belt is home to several objects that astronomers generally accept as dwarf planets: Orcus, Pluto, Haumea, Quaoar, and Makemake. These aren’t quite planets, but they’re far more than simple chunks of ice and rock. Each has its own personality, mysteries, and sometimes even their own moons.

Pluto, once considered our ninth planet, now reigns as the most famous resident of this distant realm. Originally considered a planet, Pluto’s status as part of the Kuiper Belt caused it to be reclassified as a dwarf planet in 2006. The discovery of similar-sized objects like Eris forced astronomers to reconsider what actually qualifies as a planet.

It is home to at least four known dwarf planets: Haumea, Makemake, Quaoar, and of course Pluto, with Orcus also considered a likely dwarf planet. Many of these dwarf planets have their own moons and even their own faint ring systems, with scientists recently spotting a ring around Quaoar which also has its own moon Weywot. Each world tells a unique story of formation, collision, and survival in the outer darkness.

Orbital Families and Hidden Structures

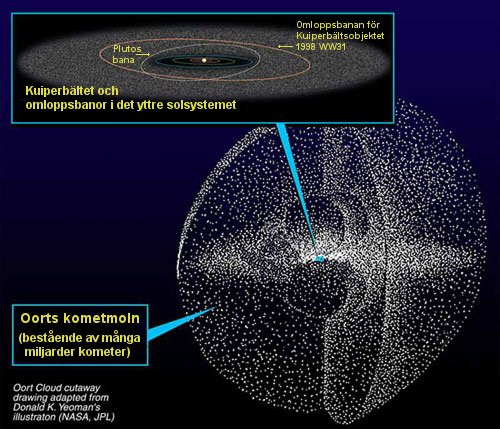

The Kuiper Belt isn’t just a random collection of icy debris scattered through space. The classification of KBOs includes three main types based on their orbital characteristics: classical (further divided into “cold” and “hot”), resonance, and scattered KBOs. Cold classical KBOs have stable, circular orbits, while hot classical KBOs exhibit more eccentric orbits. Resonance KBOs, like Pluto, maintain specific orbital relationships with Neptune. Scattered KBOs possess highly eccentric orbits that can take them far from the Kuiper Belt.

Recently, astronomers have discovered something even more intriguing. Back in 2011, a team of astronomers noticed a denser region of the objects located within the Kuiper Belt at around 44 AU. The team dubbed this region the “kernel” and found that the objects within it had low ecliptic inclinations and eccentricities compared to other KPOs.

Their algorithm found, not only the kernel, but also another distinct structure right next to it, at about 43 AU, which they simply refer to as the inner kernel. The inner kernel sticks out as potentially separate due to its eccentricity distribution being narrower than the kernel’s, suggesting a distinct population. They say the inner kernel contains 7-10% of the classical KBOs. These clustering patterns hint at complex gravitational interactions that shaped the belt over billions of years.

The Great Migration and Neptune’s Influence

The Kuiper Belt’s current structure tells a tale of cosmic upheaval. Current theories have the Kuiper Belt forming along with the rest of the Solar System, though it is still a matter of debate whether it formed in place or was pushed out to its present position as Neptune migrated outwards. The evidence suggests that our outer solar system looked very different in its youth.

This suggests that there is a distinct outer edge to the Kuiper Belt at 50 AU, an unexpected observation based on theories of how the Kuiper Belt formed. It is currently thought that this abrupt truncation of the Kuiper Belt at 50 AU marks the maximum distance that objects were transported by Neptune’s migration. As Neptune wandered outward from the Sun, it swept up countless objects and scattered them into new orbits.

The discovery could allow us to better understand how Neptune migrated from the inner solar system to its current location billions of years ago. Experts believe the planet’s outward movement caused Kuiper belt objects to temporarily be caught by Neptune’s gravitational pull, causing them to clump together. This migration explains why the belt has such a sharp outer edge and why certain orbital patterns exist today.

Our First Robotic Ambassador

For decades, the Kuiper Belt remained a realm of theoretical speculation and telescopic dots. Then came New Horizons. The first spacecraft to explore Pluto up close, flying by the dwarf planet and its moons in 2015. After a nine-year journey, New Horizons also passed its second major science target, reaching the Kuiper Belt object Arrokoth in 2019, the most distant object ever explored up close.

The Pluto flyby revealed a world far more complex than anyone had imagined. During its July 2015 flyby, New Horizons revealed Pluto to be a surprisingly varied world with craters, crevasses, glaciers, and a frozen “heart” of solid nitrogen ice. Mountains of water ice rose from plains of frozen nitrogen, while a surprisingly thick atmosphere created blue hazes reminiscent of Earth’s sky.

In early 2019, New Horizons flew past its second major science target – Arrokoth (2014 MU69), the most distant object ever explored up close. New Horizons approached Arrokoth (nicknamed “Ultima Thule” at the time) about 3.5 times closer than it came to Pluto, resulting in even more detailed pictures and other kinds of data. The spacecraft obtained the first high-resolution geological and compositional maps of a small Kuiper Belt object (KBO), while conducting sensitive searches for atmospheric activity, satellites and rings. Arrokoth turned out to be a contact binary, looking like a cosmic snowman formed when two objects gently collided and stuck together.

The Quest for Hidden Treasures

After the spacecraft passed Arrokoth, the instruments continue to have enough power to be operational until the 2030s. Team leader Alan Stern stated there is potential for a third flyby in the 2020s at the outer edges of the Kuiper belt. The hunt for New Horizons’ next target has become a race against time and distance, with astronomers scouring the sky for reachable objects.

Together, these results have ignited renewed interest in the possibility of finding a distant KBO that New Horizons could fly past in the late 2020s or even 2030s. Toward that end, our team has proposed a multiyear KBO flyby target search to NASA. If approved by NASA, that effort would initially continue the deep, groundbased KBO searches with the Japanese Subaru Telescope we’ve been using, but with more search time and a deeper search enabled by a new, high-throughput filter.

The search has revealed tantalizing hints of structure beyond the traditional belt boundaries. He said New Horizons has found evidence for a 2nd Kuiper Belt. This potential discovery could revolutionize our understanding of the outer solar system’s architecture. However, the team at the observatory expects to identify about 40,000 objects beyond Neptune in the years to come. “Forthcoming observations, including those by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time may provide further evidence for the existence of this [inner kernel] structure, and perhaps resolve the question of whether there are two distinct structures,” Siraj and his colleagues wrote in their paper.

The Kuiper Belt represents humanity’s first glimpse into the vast wilderness beyond the planets. The Kuiper Belt is truly a frontier in space – it’s a place we’re still just beginning to explore and our understanding is still evolving. Whatever your preferred term is, the belt occupies an enormous volume in our solar system, and the small worlds that inhabit it have a lot to tell us about early history. Every new discovery in this frozen realm brings us closer to understanding how our cosmic neighborhood formed and what other treasures might be waiting in the darkness beyond. The icy frontier beckons with promises of revelation that could reshape everything we think we know about planetary formation and the early history of our solar system.

What secrets do you think these ancient ice worlds might still be hiding in the depths of space? The journey of discovery has only just begun.

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.