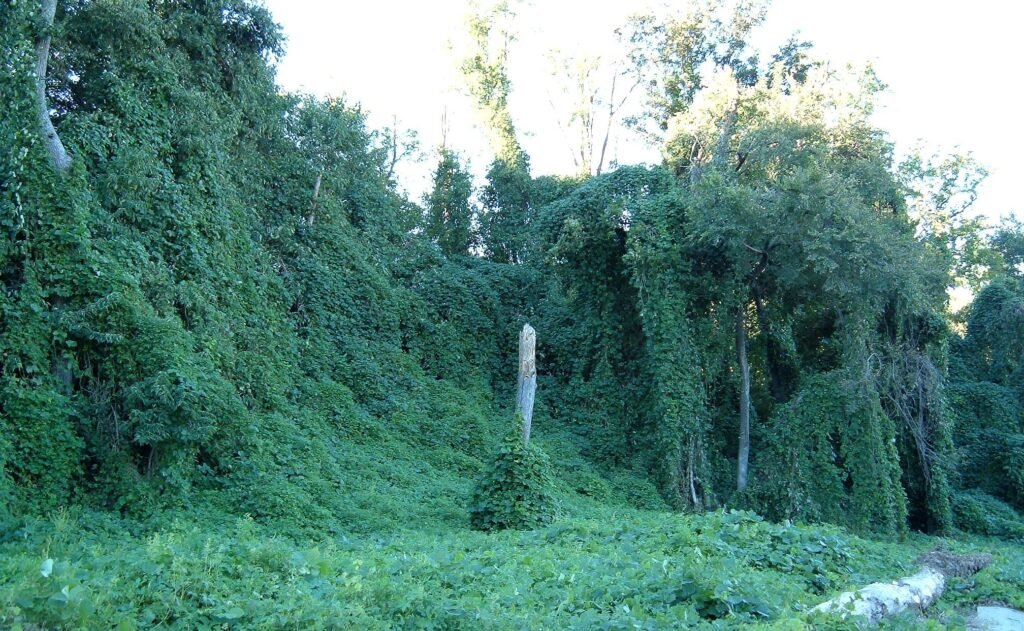

There’s a green curtain draped across the American South, an unstoppable wave of leaves and tendrils that has swallowed barns, telephone poles, and even entire hillsides. What started as an ambitious plan to save the land became one of the most enduring ecological dramas in U.S. history. Kudzu, once praised as a miracle plant, now evokes sighs and groans from farmers, scientists, and anyone who’s tried to fight its relentless grip. How did a single vine, imported with the best intentions, transform into the notorious “vine that ate the South”? This is the wild and twisting tale of kudzu—a story of hope, hubris, and the unyielding power of nature.

The Humble Beginnings: Kudzu’s Origins in East Asia

Long before kudzu tangled itself across the South, it thrived quietly in the forests and mountains of East Asia. In places like Japan and China, kudzu was just another native plant, a familiar sight along roadsides and hills. Here, it wasn’t a menace but a resource—locals used its strong fibers for weaving, its roots for medicine, and its leaves for animal feed. Kudzu had natural predators and environmental checks that kept it in line. No one in those temperate regions could have predicted the plant’s explosive future across the ocean.

World’s Fair Debut: Kudzu Arrives in America

The United States first met kudzu at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, a world’s fair celebrating America’s 100th birthday. Visitors marveled at the lush, fast-growing vine with its sweet-smelling purple flowers. American gardeners and horticulturists were enchanted, taking home seeds and saplings. Kudzu was soon seen as a beautiful addition to Southern porches and arbors, its broad leaves providing cool shade in the sticky summer heat. No one seemed to worry about its potential for mischief back then.

Government Endorsement: The Solution to Southern Erosion

After the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, erosion became a national crisis. The bare, eroded hills of the South looked like open wounds on the landscape. Federal agencies searched desperately for a quick fix, and kudzu seemed to be the answer. The Civilian Conservation Corps and Soil Conservation Service distributed millions of seedlings, paying farmers up to eight dollars an acre to plant them. Kudzu’s rapid growth was hailed as a miracle—within a single season, barren hills burst into green. The government even ran radio jingles praising the plant: “Kudzu covers Dixie like the dew!”

The Science of Kudzu: What Makes It Grow So Fast?

Kudzu is a master of survival, with a growth rate that can top a foot per day in the right conditions. Its secret weapon is nitrogen fixation, a process where the plant’s roots host special bacteria that pull nitrogen from the air, fertilizing the soil. Kudzu’s leaves are broad and efficient, soaking up sunlight and sending energy racing underground to tuberous roots as big as bowling balls. The vine’s tendrils twist and climb, grabbing onto anything in their path and smothering competitors. In the warm, humid South, where winters are mild and growing seasons are long, kudzu found paradise.

From Friend to Foe: Kudzu’s Unchecked Spread

By the 1950s, the honeymoon was over. Kudzu began to outgrow its welcome, swallowing fields, forests, and even abandoned cars. Without its native pests and diseases, nothing seemed to stop its march. The very qualities that made kudzu a hero—its speed, resilience, and hardiness—now made it a villain. Farmers watched in disbelief as their crops disappeared under waves of green. Telephone companies groaned at the cost of clearing vines from poles and lines. Entire communities realized they had unleashed a botanical juggernaut.

Kudzu’s Ecological Impact: Smothering the South

Kudzu doesn’t just cover the landscape; it changes it. As the vine crawls over trees, it blocks sunlight, slowly starving and killing the native plants underneath. Forests that once teemed with birds and wildflowers become dark, quiet thickets of kudzu. The loss of native vegetation ripples through the ecosystem—songbirds lose nesting sites, pollinators lose flowers, and the natural balance shifts. In some places, kudzu has even altered soil chemistry, making it harder for native species to recover.

The Human Toll: Farmers, Homeowners, and the Fight Against Kudzu

For many Southerners, battling kudzu became a way of life. Farmers spent countless hours and dollars mowing, burning, and spraying herbicides. Homeowners watched helplessly as their yards, fences, and even homes disappeared beneath the vines. Community groups organized “kudzu festivals” with contests to see who could clear the most. Despite these efforts, the plant often came back stronger, sprouting from roots deep underground. The frustration was palpable—fighting kudzu felt like a never-ending battle.

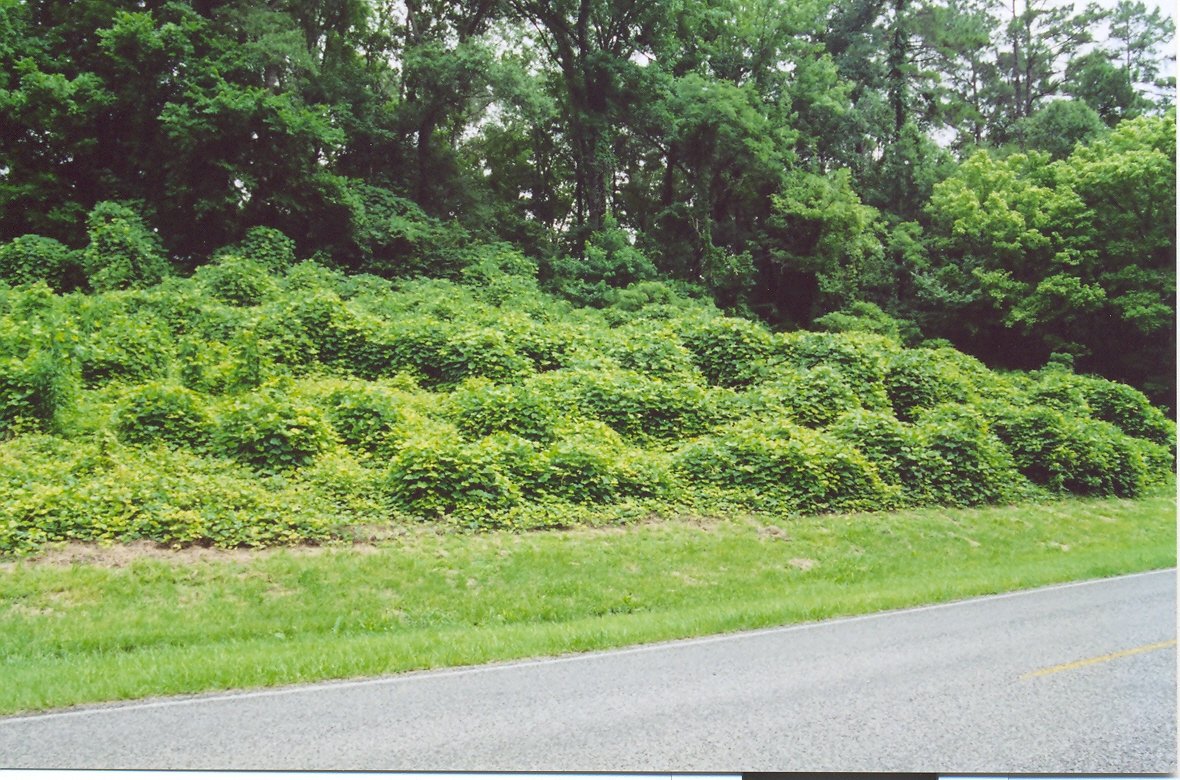

The Economics of Invasion: Kudzu’s Cost to the South

The financial burden of kudzu is staggering. Utility companies spend millions each year clearing vines from power lines and substations. Transportation departments must regularly cut back kudzu along highways, where it can obscure signs and create hazards. Farmers lose valuable pasture and cropland, sometimes giving up entire fields to the relentless invader. According to recent studies, the total economic impact of kudzu in the U.S. approaches hundreds of millions of dollars annually. It’s a silent tax on the Southern way of life.

Kudzu and Wildlife: Winners and Losers

Kudzu’s impact on wildlife is a mixed bag. Some animals, like deer, find the leaves tasty and nutritious, and a few birds nest in the dense foliage. But for most native species, kudzu is bad news. The thick cover can drive out ground-nesting birds, reduce habitat for small mammals, and eliminate the wildflowers and shrubs that many animals depend on. In forests, the death of native trees due to kudzu’s smothering can lead to long-term changes in the composition of plant and animal communities.

A Changing Climate: Is Kudzu Marching North?

As winters become milder and growing seasons stretch longer, kudzu’s range is creeping northward. Reports of kudzu infestations now come from as far north as Illinois, Pennsylvania, and even parts of Canada. Scientists worry that, given the right conditions, kudzu could colonize much larger swaths of the United States. Climate change is tilting the playing field, and plants like kudzu are poised to take advantage. The vine that once seemed like a Southern curiosity could soon become a national concern.

Creative Uses: Turning Kudzu into an Ally?

Not all stories about kudzu are grim. Some enterprising folks have found ways to make the best of a bad situation. Kudzu’s strong fibers can be woven into baskets and crafts. Its roots contain starch that can be used in cooking, and some herbalists tout the plant’s medicinal properties. Artists use kudzu as a natural dye, and chefs have experimented with recipes from kudzu jelly to fritters. While these creative uses won’t get rid of kudzu, they show that humans can adapt and innovate—even in the face of a relentless invader.

The Science of Control: Can We Beat Kudzu?

Scientists have tried everything to contain kudzu—herbicides, controlled burns, grazing goats, and even biological agents. Each approach has its pros and cons. Herbicides can be effective but may harm other plants and pollute the soil. Goats love kudzu, but they can’t reach every vine and may eat desirable plants, too. Some researchers are studying fungi and insects from kudzu’s native range that might help control it. While total eradication seems unlikely, integrated management offers hope for keeping kudzu in check.

Kudzu in Popular Culture: From Folklore to Fear

Kudzu has slithered its way into books, songs, and even horror films. Southern writers use it as a symbol of unstoppable change—sometimes funny, sometimes terrifying. In comics and cartoons, kudzu is the punchline to jokes about Southern life. The phrase “the vine that ate the South” has become part of American folklore, capturing both the humor and the frustration of living with this tenacious plant. Kudzu’s story has become a metaphor for unintended consequences and the unpredictable power of nature.

Scientific Curiosity: What Kudzu Teaches Us About Invasives

The saga of kudzu offers powerful lessons for scientists and policymakers. It shows how introducing a species without fully understanding its potential impact can lead to disaster. Kudzu’s success is a case study in ecological imbalance—a reminder that nature rarely reacts the way we expect. Researchers now use kudzu as a model to study invasive species, learning how plants adapt and spread in new environments. These insights help guide modern approaches to preventing and managing biological invasions.

Global Perspective: Kudzu and the Invasive Species Crisis

Kudzu isn’t alone—globally, invasive species are a leading cause of biodiversity loss. From zebra mussels in the Great Lakes to cane toads in Australia, the world is grappling with the fallout from species introduced beyond their native range. Kudzu’s story resonates far beyond the South, serving as a cautionary tale about the risks of moving plants and animals around the globe. It’s a reminder that well-meaning actions can have unintended, far-reaching effects.

A Personal Connection: Living with Kudzu

If you’ve spent any time in the South, chances are you’ve seen kudzu’s emerald waves rolling over hillsides and highways. For many, it’s a backdrop to childhood memories—summer road trips, picnics under leafy arbors, or the endless chore of clearing the yard. Some people feel a strange fondness for its lush beauty, while others see only frustration and loss. Either way, kudzu is woven into the fabric of Southern life, a living reminder of both human ingenuity and folly.

The Future of Kudzu: Lessons for Tomorrow

Looking ahead, the story of kudzu is far from over. Scientists, land managers, and ordinary citizens continue to search for smarter, more sustainable ways to manage invasive plants. There’s hope in new research, community action, and a deeper understanding of how ecosystems work. The vine that once promised salvation now demands respect—and caution. As we face new environmental challenges, kudzu’s legacy remains a powerful lesson in humility and the unpredictable dance between people and nature.