It sounds like a fable, but the protagonist is real: a pinhead-sized jellyfish capable of turning back its biological clock. Scientists call it Turritopsis dohrnii, better known as the so‑called immortal jellyfish, and it can revert from adulthood to its juvenile state when life gets rough. That trick doesn’t just dodge death; it rewrites what we thought an animal body could do. For decades, the mystery lingered in scattered lab notes and quiet aquarium tanks while biologists tried to catch the creature in the act. Now, detailed studies are illuminating how this jelly resets itself – cell by cell – and what that might mean for aging, medicine, and our changing oceans.

The Hidden Clues

Imagine an adult animal slamming the brakes on death and becoming a baby again – no eggs, no embryos, just a clean restart. That’s the headline move Turritopsis dohrnii pulls when injury, starvation, or sudden temperature swings hit. The adult medusa shrinks, sheds its tentacles, and collapses into a floating speck that anchors to a surface. From that unassuming dot, a new colony of polyps sprouts, which later bud new medusae, genetically identical to the original. In a world where most creatures march one way down life’s timeline, this jellyfish finds the side door.

The first time I saw one under a microscope, it looked like a fragile glass button with eyelashes for tentacles – hardly a rule-breaker. But the clues were there in its resilience, the way its tissues didn’t just heal; they reconfigured. It felt less like bandaging a wound and more like rebooting a computer. Every reversal seemed to say: the end isn’t the end if your cells remember how to start over. It’s a plot twist hidden in plain sight.

From Tidepool to Lab Bench

Turritopsis dohrnii likely began its reputation in the Mediterranean, but ships, currents, and time have helped it turn up in distant ports. In aquaria, researchers learned to trigger reversals by stressing the medusae, then watched the process unfold over days. Early accounts were easy to dismiss – jellyfish can be notoriously tricky to keep and identify – but repeated experiments slowly built a persuasive record. The same adult, over and over, could loop back to youth without spawning. Against the standard arc of birth, growth, reproduction, and death, the jellyfish offered a circular plot.

As lab techniques improved, keeping stable cultures got easier, and observations grew more systematic. Scientists began cataloging each stage: the fading medusa, the cyst-like blob, the creeping stolons, the budding polyps. The sequence wasn’t random improvisation; it was choreography. What looked like mush was actually a careful stepwise program. That realization nudged the story from curiosity to biology lesson.

How the Reversal Works

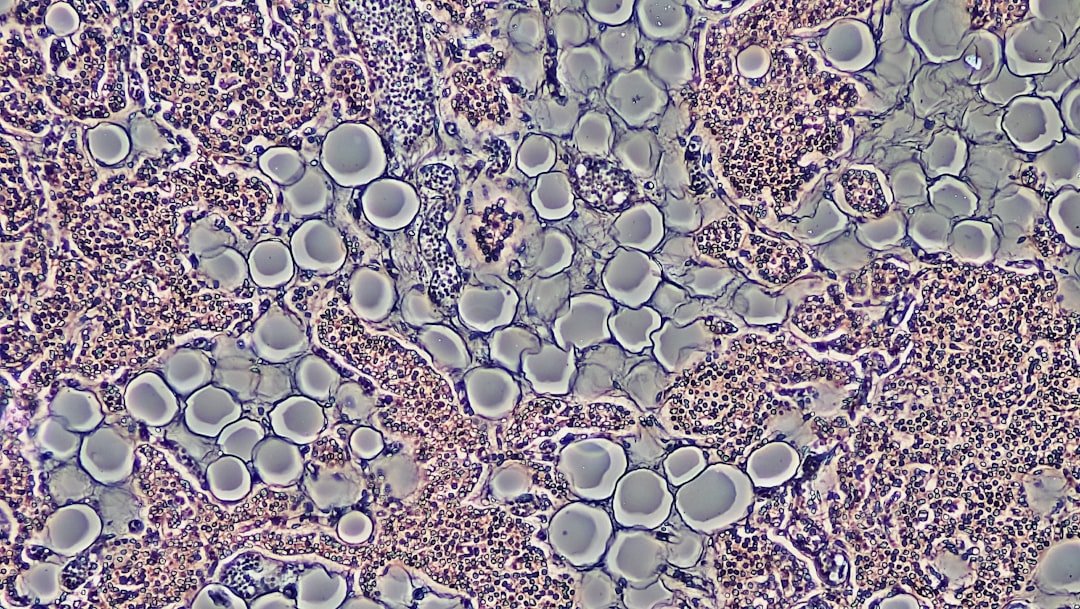

In its normal life cycle, a free-swimming medusa is the showy, bell-shaped stage, while the polyp is a tiny, plant-like colony anchored to rock or shell. When crisis hits, the medusa effectively calls time-out and melts into a compact mass of cells. Those cells reorganize, attach, and grow into a polyp stage capable of cloning new medusae. It’s not merely healing; it’s re-specifying identity, a process biologists call transdifferentiation. Different adult cells seem to take on new fates without passing through a classic embryonic phase.

- Typical triggers include physical injury, food scarcity, and abrupt temperature changes.

- The reversal can produce multiple polyps, meaning one stressed medusa may seed a whole mini-colony.

- The vast majority of jellyfish cannot do this; they die after reproduction or injury.

Genes That Bend Time

Comparative genomic studies suggest this species carries a toolkit tuned for resilience: genes tied to DNA repair, telomere maintenance, and stem-like plasticity appear emphasized. Some gene families linked to maintaining genome stability and controlling cell identity show expanded copy numbers or unique variants. Researchers also report adjustments in pathways that balance cell survival and programmed cell death, hinting at careful control rather than reckless immortality. When the medusa reverses, genes toggle like switches in a reprogramming panel, steering tissues back to polyp architecture. It’s a molecular dialect of the same language that lets our own cells reset in the lab under the right cues.

I think of it like a library with extra copies of the manuals for fixing broken pages and rebinding old books. Most animals have some repair manuals on the shelf; this jellyfish seems to stock the premium editions. During reversal, the librarians don’t just mend; they re-shelve entire sections. The result isn’t a patched-up adult – it’s a coherent juvenile system rebuilt from the ground up. That’s a different kind of mastery.

Why It Matters

In aging research, we usually compare genomes, count damaged molecules, and test how diet or drugs tweak lifespan in model species like worms, flies, and mice. Turritopsis dohrnii doesn’t just slow the clock; it flips it, offering a fundamentally different perspective on plasticity. Instead of asking how to delay decline, it asks how an adult identity can be safely taken apart and reassembled. That reframes debates about regenerative medicine, where the challenge is resetting cells without inviting chaos like tumors. The jellyfish’s controlled reversal hints at a blueprint for stability during profound change.

Compared with traditional anti-aging strategies – calorie restriction, stress-response tuning, senescence clearing – this approach is radical yet instructive. It suggests longevity isn’t only about resisting damage but about retaining the option to reboot systems when damage accumulates. The trade-offs matter: animals that reprogram too loosely risk cancer; those that never reprogram get brittle. This species appears to walk the narrow ridge between flexibility and control. If we can map that ridge, we might build safer cellular therapies.

Global Perspectives

Turritopsis dohrnii is tiny, easily overlooked, and not an obvious threat to people, but its story travels with global shipping and warming seas. Ports and marinas become accidental research stations as polyps hitch rides on hulls and docks. Jellyfish blooms already challenge fisheries and tourism in many regions, and while this species isn’t the usual culprit, its stealthy presence reminds us how marine life can spread. Understanding its biology helps us spot lookalikes and avoid overhyping risk. Not every jellyfish swarm is a crisis, and not every newcomer is invasive.

At the same time, globalization makes laboratory access easier: small field teams can collect specimens, while international groups share protocols and gene data. This cross-border flow turns a local curiosity into a global case study in resilience. For coastal communities, the lesson is that tiny species can carry outsized scientific value. For young scientists, it’s a gateway organism – simple enough to handle, deep enough to surprise. The ocean keeps handing us puzzles; this one just happens to reset itself.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Marine biologists once relied on hand lenses, sketchbooks, and patience to track life histories in tidepools. Today they add single-cell sequencing, high-resolution imaging, and computational models to see which cells change fate and when. Old questions – what triggers the switch, which tissues go first – now meet new datasets that clarify timing and gene networks. Classic experiments of stressing medusae sit beside heat maps of gene expression, giving the narrative both a plot and a script. The combination tightens the evidence from anecdote to mechanism.

There’s a pleasing symmetry here: centuries-old natural history still matters, yet advanced tools unlock the hidden steps. Watching a medusa thin and curl is still step one; decoding the molecular levers is step two. Each confirms the other, preventing our imagination from running ahead of the facts. That’s how a headline-grabbing idea becomes a robust story. The jellyfish remains humble, the technology ambitious, and the science better for both.

The Future Landscape

Next-generation studies will likely map every cell type through a full reversal, building atlases that show who becomes what and in which order. CRISPR and related tools can test the role of candidate genes that safeguard reprogramming without derailing tissue control. Expect more comparative work with species that age differently – hydra, planarians, and long-lived bivalves – to separate universal rules from jellyfish quirks. The toughest challenge may be translating circular life cycles into therapies for linear bodies like ours. We don’t need to become polyps; we need to reset safely inside one body plan.

There are also ecological and ethical questions: what happens if we engineer super-resilient cells beyond medical need, or release modified organisms unintentionally? Laboratory containment, data transparency, and careful oversight will matter as much as experimental brilliance. Still, the practical payoffs are compelling – better tissue repair, gentler rejuvenation, and drugs that nudge cells toward recovery rather than endless division. I’m cautiously optimistic, the way you are when a map finally shows the hidden path you suspected. It’s not a shortcut, but it might be a smarter route.

What You Can Do

Stay curious about the quiet corners of the sea – support local aquariums, read marine research newsletters, and share responsible coverage when this jellyfish pops into the news. If you live near the coast, join community science projects that document small invertebrates; better records make better science. Reducing plastic and runoff helps the habitats where polyps settle, improving water quality for everything from corals to copepods. If you have the means, donate to labs that study regeneration and aging; the basic science you fund today becomes tomorrow’s therapy. I keep a small notebook for unanswered questions I find on beaches and in papers; most breakthroughs begin as scribbles like those.

Above all, resist the myth that nature’s marvels are magic. They’re mechanisms waiting to be understood, and understanding is something everyone can help advance. Even a jellyfish the size of a pinkie nail can teach us how to heal. The next clue might come from a harbor piling you’ve walked past a hundred times. What might you notice the hundred and first?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.