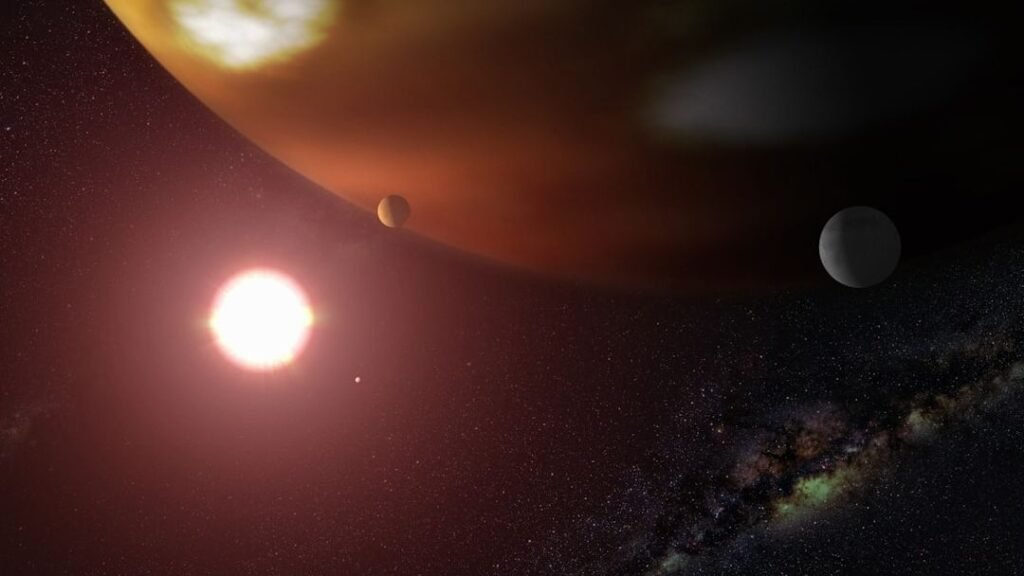

Look up at the night sky and it feels calm, timeless, almost frozen. But the story of our solar system is anything but calm. It’s a history of chaos and collisions, worlds being built and destroyed, and orbits shifting like musical chairs. The planets we see today are the survivors of a much wilder, messier past than most of us were ever taught in school.

Over the last few decades, astronomers have quietly rewritten almost everything we thought we knew about how our cosmic neighborhood formed. New space missions, supercomputer simulations, and discoveries of thousands of planets around other stars have revealed a stunning picture: our solar system is not a simple, clockwork model but the result of lucky breaks, violent impacts, and delicate balancing acts that could easily have gone another way.

A Cloud of Gas, Dust, and Trouble: The Birthplace of the Solar System

At the very beginning, there were no planets, no Sun, just a cold, giant cloud of gas and dust drifting in the Milky Way. Something disturbed that cloud – likely the shockwave of a nearby exploding star – and caused it to start collapsing under its own gravity. As it fell inward, the material began to spin faster, flattening into a rotating disk with a growing, hot ball of gas in the center that would become the Sun.

Most of the material in this disk was hydrogen and helium, but a small fraction was heavier elements like carbon, oxygen, silicon, and iron – recycled from earlier generations of stars that had lived and died. Those tiny grains and ice-coated particles started sticking together, first by static forces and then by gravity, forming clumps that grew from dust to pebbles to boulders. It sounds slow and gentle, but in reality the young solar system was a noisy construction site where collisions, shattering, and mergers were happening all the time.

From Dust to Planets: How Worlds Slowly Assembled

Once chunks of rock and ice grew large enough – many kilometers across – they became what scientists call planetesimals, the building blocks of planets. These objects pulled in smaller debris with their gravity and occasionally collided with one another, sometimes merging, sometimes fragmenting into rubble. Over millions of years, the biggest bodies in each region slowly dominated, sweeping up material and carving out clearer orbits around the Sun.

Closer to the Sun, where temperatures were higher, only metal and rock could survive, so the inner planets like Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars turned out small and dense. Farther out, beyond what’s called the snow line, water and other ices could stay solid, giving rise to huge planetary cores that could quickly grab gas and become giants like Jupiter and Saturn. This inside‑out contrast is one of the reasons our solar system has both small rocky worlds and massive gas and ice giants, rather than a random mix.

The Giants on the Move: Jupiter, Saturn, and the Great Planetary Migration

For a long time, textbooks quietly assumed the planets formed more or less where we see them now. That idea has basically fallen apart. Computer models and the study of planets around other stars show that giant planets often migrate, drifting inward or outward as they interact with the gas disk and with each other. Our own Jupiter and Saturn almost certainly did not stay put; they likely moved substantial distances before settling into their current orbits.

One influential idea suggests that Jupiter may have originally moved inward, scattering material and reshaping the inner solar system, before reversing course when it interacted with Saturn and moving outward again. This kind of migration would help explain why the inner planets are relatively small and why Mars is oddly tiny compared with Earth and Venus. The wandering of these giants also helps account for the structure of the asteroid belt, which looks less like a failed planet and more like a scar from repeated gravitational stirring.

The Cataclysm Years: Impacts, Moons, and a Violent Young Earth

The early solar system was crowded and unforgiving, and big collisions were not rare accidents but part of the normal process of building planets. Earth itself likely owes its Moon to a catastrophic impact with a Mars‑sized object in the first hundred million years or so. That collision would have melted and vaporized huge amounts of rock, flinging debris into orbit that eventually clumped together to form the Moon we see today. The chemistry of lunar rocks, so similar to Earth’s outer layers, is one of the key clues pointing to this dramatic origin.

Around the same general era, many worlds were being battered by leftover planetesimals and fragments, in an extended period of heavy bombardment. The pockmarked surfaces of the Moon and Mercury are like fossil records of that violent time, still preserving impact scars billions of years later. On Earth, plate tectonics, erosion, and weather have erased almost all of those oldest craters, but traces remain in ancient minerals and in the odd compositions of some meteorites that still fall from space today.

Water, Atmospheres, and the Making of Habitable Worlds

One of the most haunting questions in this whole story is how a once‑molten Earth ended up with oceans, clouds, and a breathable atmosphere. Water likely arrived from a mix of sources: some embedded in the materials that built Earth, some delivered by icy objects from farther out, such as certain types of asteroids and possibly a smaller contribution from comets. Studies of hydrogen and other isotopes in Earth’s water and in meteorites have helped connect these dots and show that space rocks played a huge role in seeding our planet with the ingredients for life.

At the same time, early atmospheres were being built, stripped, and rebuilt by volcanic eruptions, impacts, and the harsh radiation of the young Sun. Venus may once have been more Earth‑like before a runaway greenhouse effect cooked its surface and thickened its atmosphere to crushing levels. Mars seems to have lost much of its air and water over time, likely due to its smaller size and a weaker magnetic field that left it exposed to the solar wind. The very different fates of these three neighbors show how delicate the balance is between a sterile rock and a living world.

The Outer Frontier: Kuiper Belt, Oort Cloud, and the Frozen Archives

Beyond Neptune lies a realm that used to be little more than a blank space in diagrams, but it’s actually one of the most revealing parts of the solar system’s history. The Kuiper Belt is a wide, icy region filled with small worlds and dwarf planets like Pluto and Eris, relics from the era of planet formation that were never incorporated into larger planets. Their odd orbits and varied compositions are like puzzle pieces, hinting at how the giant planets moved and how material was scattered outward.

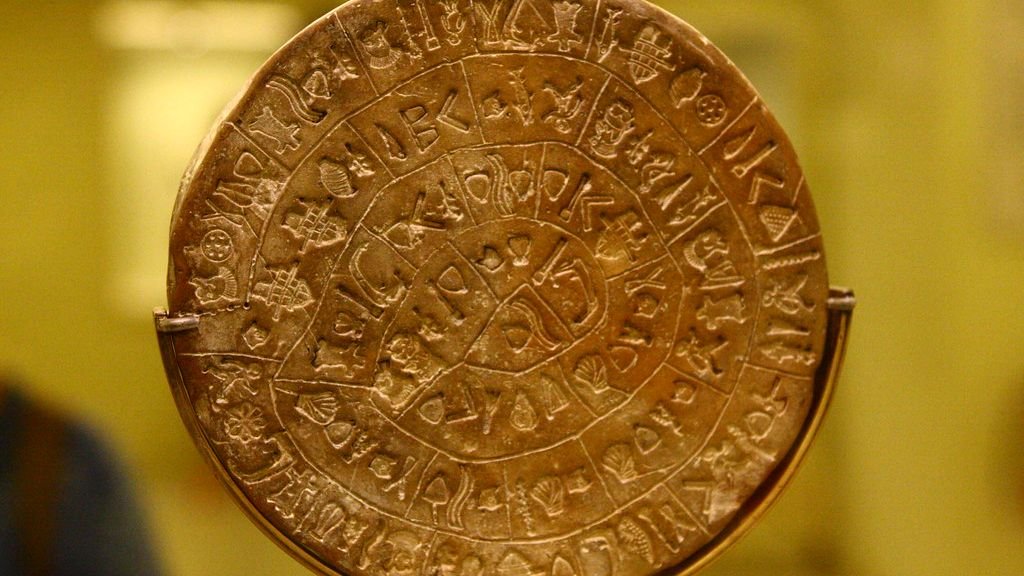

Even farther away, in a sphere extending far beyond what we can directly see, lies the hypothetical Oort Cloud, a vast reservoir of icy bodies that occasionally send comets plunging toward the inner solar system. These deep‑freeze regions act like time capsules, preserving the conditions of the early solar nebula in ways that rocky planets cannot. Every comet we study, every flyby of a distant icy world, adds another line to the hidden diary of how and where our system was assembled.

A Living System: Ongoing Change and the Future of the Solar Neighborhood

It’s tempting to think the solar system finished forming billions of years ago and has been mostly static ever since, but that’s not really true. Orbits still slowly shift under the influence of gravity, small bodies still collide and fragment, and the Sun itself is changing as it burns through its fuel. Space missions have watched active processes in real time, like geysers on Saturn’s moon Enceladus or changing ice caps on Mars, reminding us that this is not a museum exhibit but a living system.

Far in the future, the story will take another dramatic turn when the Sun swells into a red giant, likely swallowing Mercury and Venus and severely altering Earth. The outer planets and distant icy bodies will experience their own changes as the Sun sheds mass and its gravitational hold weakens. The solar system’s hidden history is still being written, just on timescales so long that we only see tiny snapshots. Knowing that, it’s hard not to look up and wonder what chapter we’re in right now.