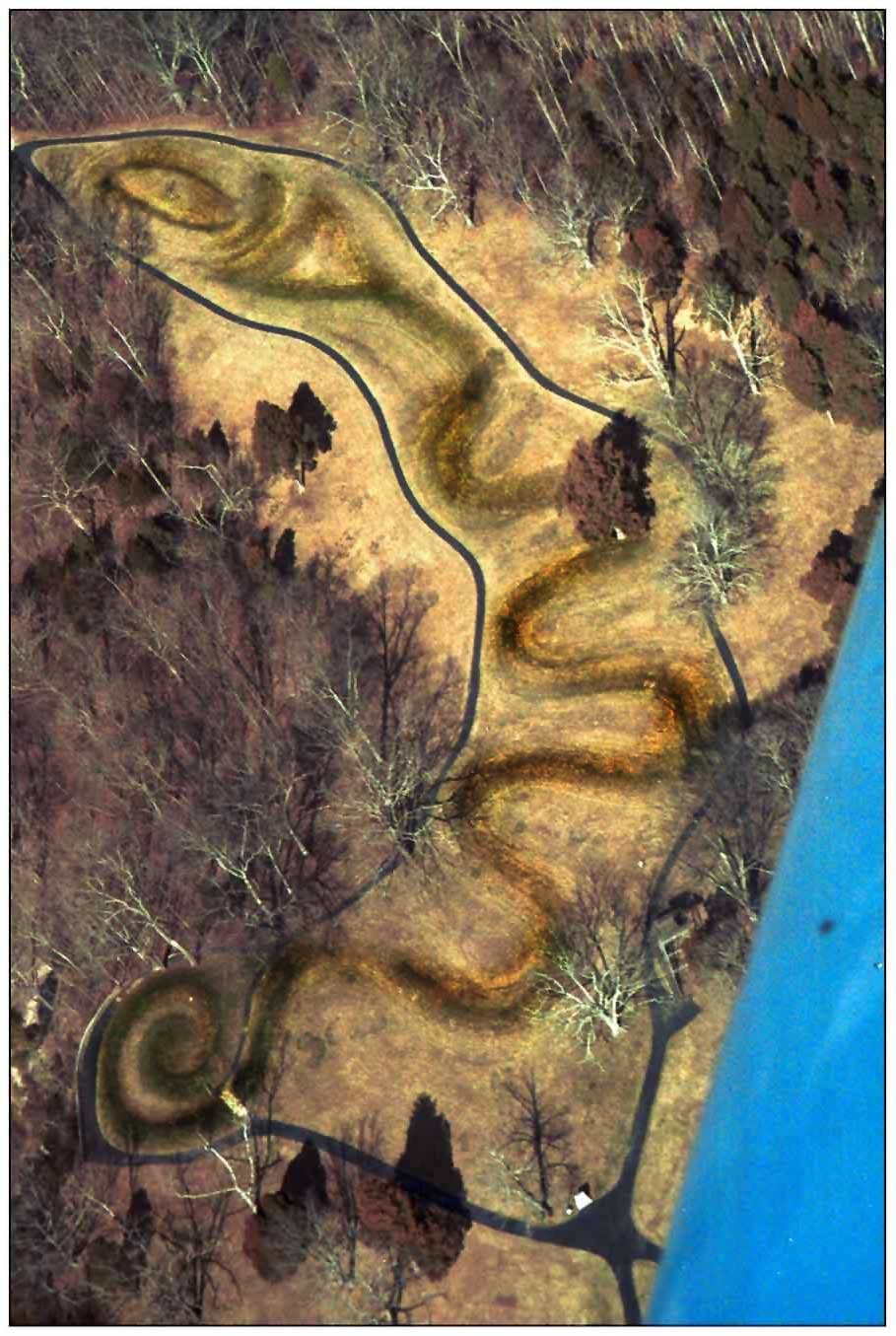

Deep in the rolling hills of Adams County, Ohio, something extraordinary coils across the landscape like a massive creature frozen in time. Stretching over 1,300 feet in length and rising three feet from the earth, the Great Serpent Mound has captivated visitors, scientists, and mystery-seekers for centuries. This ancient earthwork – the largest serpent effigy in the world – sits perched on the edge of a 300-million-year-old meteor crater, its undulating form winding across the plateau like a giant snake caught in eternal motion. But what exactly were the ancient builders trying to tell us? Was this magnificent creation simply a work of art, or does it serve as one of humanity’s oldest astronomical calendars?

The Puzzle That Refuses to Solve Itself

The Great Serpent Mound represents one of archaeology’s most enduring mysteries, with radiocarbon dating yielding conflicting results that place its construction anywhere from 300 BC to 1100 AD. Harvard University archaeologist Frederic Ward Putnam excavated Serpent Mound in the late 19th century, but he found no artifacts in the Serpent that might allow archaeologists to assign it to a particular culture. This absence of cultural markers has left scientists in the dark about who built this massive earthwork and why. Unlike typical burial mounds that contain artifacts, pottery, or human remains, the Serpent stubbornly keeps its secrets buried beneath tons of carefully placed earth. Because it’s just made out of earth – with some repairs over the years – precise dating is tricky. Archaeologists agree that the ancestors of American Indians built the mound, but disagree about which particular ancestors. This uncertainty has turned the Serpent into a kind of archaeological Rorschach test, where different experts see different truths in its ancient curves.

A Serpent Born from Cosmic Violence

The Serpent Mound sits on what’s known as the Serpent Mound crater, an eroded meteorite impact crater that’s estimated to be 8 kilometers wide and less than 320 million years old. The placing of the head of the snake is around a promontory over a creek in part created by a meteorite that hit somewhere around 300 million years ago. This cosmic connection isn’t just geological coincidence – it may have been precisely why ancient peoples chose this spot for their monumental creation. There are documented anomalies in the geomagnetic fields inside the crater and the immediate environs of the Serpent Mound protected effigy mound site, which may explain why the original mound builders and subsequent indigenous tribes were attracted to the site. The ancient builders somehow recognized that this place was special, different from the surrounding landscape in ways that modern science is only beginning to understand. Whoever built it “certainly knew that this place was unique” based on the geology, even if they didn’t know the meteorite was a meteorite.

The Summer Solstice Revelation

In 1987, Clark and Marjorie Hardman published their finding that the oval-to-head area of the serpent is aligned to the summer solstice sunset. This discovery transformed how archaeologists viewed the Serpent, shifting focus from pure artistry to astronomical function. If you visit Serpent Mound near Peebles, Ohio on June 20th/21st, this time at sunset, you will see the wide-open mouth of the serpent effigy on the ground appear to swallow the sun as it sets over a hill in the distance known as Solstice Ridge. Serpent Mound is open on the Summer Solstice, June 20th 2025, until 9:30 p.m. This celestial alignment isn’t merely coincidental – it represents sophisticated astronomical knowledge that required careful planning and precise construction. The builders had to understand not just where the sun sets on the longest day of the year, but how to position a massive earthwork to capture that moment perfectly. The mound’s design ingeniously places the head to perfectly coincide with this solstice moment, while the tail points towards the winter solstice sunrise.

Beyond the Solstice: Multiple Astronomical Alignments

Some think the three main curves of the serpent’s body point to the Summer Solstice sunrise, the Equinox sunrise and the Winter Solstice sunrise, while others believe they are aligned to the Minimum Northern Moonrise and the Maximum Southern Moonrise. The complexity of these potential alignments suggests something far more sophisticated than simple sun-watching. What researchers discovered when looking at the deviations from the average full moon rise positions was that the spread of actual moon rises around the average rise positions matched the widths of the eastward-bowing curves of the serpent’s body – the centerlines of the pointers mark the average full moon rises nearest the solstices and equinoxes and the widths of the curves indicate the range of variation. This suggests the ancient builders understood not just solar cycles, but the complex 18.6-year lunar cycle as well. Many of the earthworks created by the ancestors of contemporary American Indians are aligned to points on the horizon marking key rise and set points for the sun and moon, and it may have been a way of linking these sacred sites to the rhythms of the cosmos or it may have allowed the sites to serve as calendars.

The Precision Problem That Baffles Scientists

The head of the serpent actually points about 1.2° south of the true summer solstice sunset point, a misalignment that has troubled other researchers since the apparent size of the sun in the sky is about 1/2°, so a misalignment of over two solar diameters would be very noticeable to anyone. This “error” puzzled scientists for decades until some researchers proposed a different interpretation. What they found was that the serpent’s head does not mark the summer solstice but marks out an interval 15 days either side of the solstice, a one-month interval overall – the moon is not necessarily full on the solstice itself, but it would be full at some point in this interval, identifying a special full moon: the full moon closest to the summer solstice. This suggests the builders weren’t aiming for surgical precision in solar alignment, but rather creating a window for lunar observations. Whatever group had the technical sophistication to construct Serpent Mound would have been able to pinpoint the summer solstice sunset to far greater precision. The “imprecision” might actually be intentional astronomical sophistication.

A Calendar Carved in Earth

If the three main curves of the serpent’s body point to the Solstices, Equinoxes, or lunar phases, it’s possible the mounds acted as a seasonal “calendar,” perhaps helping the natives keep up with their crops. This practical function would have been crucial for agricultural societies that needed to know precisely when to plant, tend, and harvest their crops. This snake has rested here for nearly 1,000 years, the solstice alignment suggesting that one of the effigy’s purposes was to mark the turning of the year so that planting and gathering and hunting could be planned. The Serpent would have served as a massive, permanent timepiece visible from considerable distances, allowing entire communities to coordinate their activities with celestial cycles. Unlike portable calendars, this earthen calendar couldn’t be lost, stolen, or destroyed by weather. It was built to last millennia, and it has. Solar and lunar alignments tell us that people all around the world have been looking to the heavens for a long time because they know that life comes from the sun, ultimately.

The Adena Culture: Early Candidates for the Builders

Based largely on the nearby presence of Adena burial mounds, later archaeologists attributed the effigy to the Adena culture that flourished from 800 B.C. to A.D. 100. Like other peoples of the Woodland period, the Adena culture were hunter-gatherers, with women domesticating and cultivating various crops such as squash, sunflower, sumpweed, goosefoot, knotweed, maygrass, and tobacco, often living in small villages with surrounding gardens but moving frequently to follow animal herds. The Adena were sophisticated mound builders who created burial complexes throughout the Ohio Valley, making them logical candidates for the Serpent’s construction. The Adena were known for their burial practices, burying their dead in prominent mounds throughout the midwest, with many archaeologists believing that these structures served as territorial markers, often accompanied by small circular earthen enclosures that many archaeologists believe were once used for rituals. Their cultural practices and geographical presence make them prime suspects in the Serpent’s creation, though definitive proof remains elusive.

The Fort Ancient Alternative: A Later Construction Theory

A 1991 site excavation used radiocarbon dating to determine that the mound was approximately 900 years old, suggesting that the builders of the Serpent belonged to the Fort Ancient culture (A.D. 1000–1500). The Adena culture is not known to have built effigy mounds or to have used serpent symbolism in their art, whereas the Fort Ancient culture built the Ohio Alligator Mound and frequently depicted serpents in their art, leading to assessments that conclude the best available data indicate that Serpent Mound was built by the Fort Ancient culture. This evidence shifts the timeline considerably, placing the Serpent’s construction closer to the medieval period rather than ancient times. The Fort Ancient people were accomplished astronomers and engineers who built complex earthworks throughout the region. Two Late Precontact stone serpent effigies in the valley below the Fort Ancient Earthworks also have alignments to the sun, which supports a Late Precontact age for the sun-aligned Serpent Mound. Their documented use of serpent imagery and astronomical alignments makes them equally plausible candidates for the Serpent’s construction.

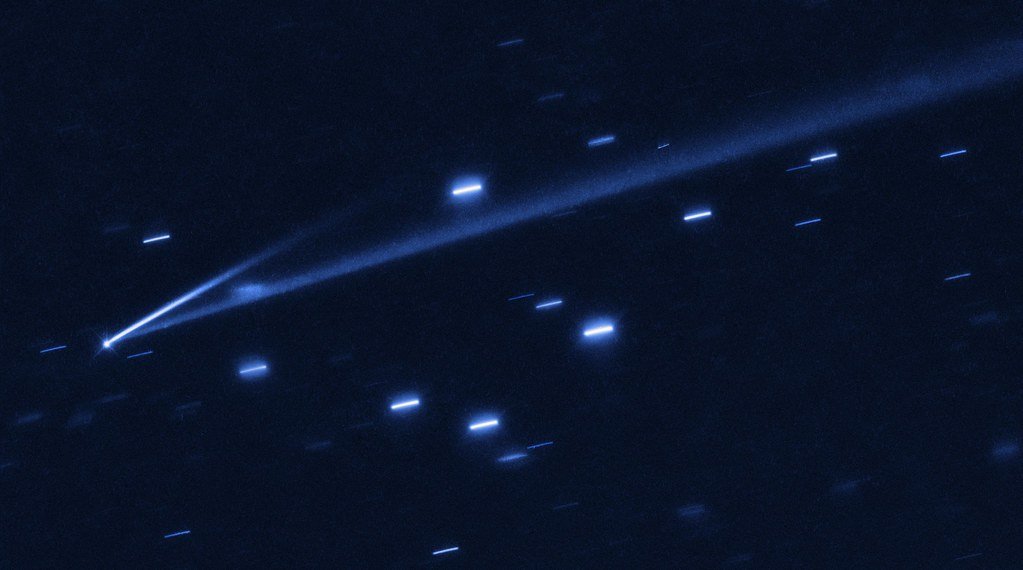

Cosmic Influences: Supernovas and Comets as Inspiration

The primary theory is that the light from a supernova may have prompted its construction – the one that created the Crab Nebula occurred in the year 1054 CE, and the light of the supernova would have been visible for two weeks after it first reached earth and was visible in broad daylight. Imagine the impact such a celestial event would have had on ancient peoples: a new star suddenly blazing in the sky, bright enough to see during daylight hours. Some archaeologists suggest the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1066 CE could have been the influence and that the tail of Halley’s Comet could have influenced the shape of the mound; however, the tail of the comet has always appeared as a long, straight line that does not resemble the curves of the Serpent Mound. These cosmic events would have been interpreted as profound spiritual messages, possibly inspiring the construction of monuments designed to capture and commemorate such divine communications. The timing aligns roughly with the Fort Ancient construction theory, suggesting these astronomical phenomena may have directly influenced the decision to build the Serpent.

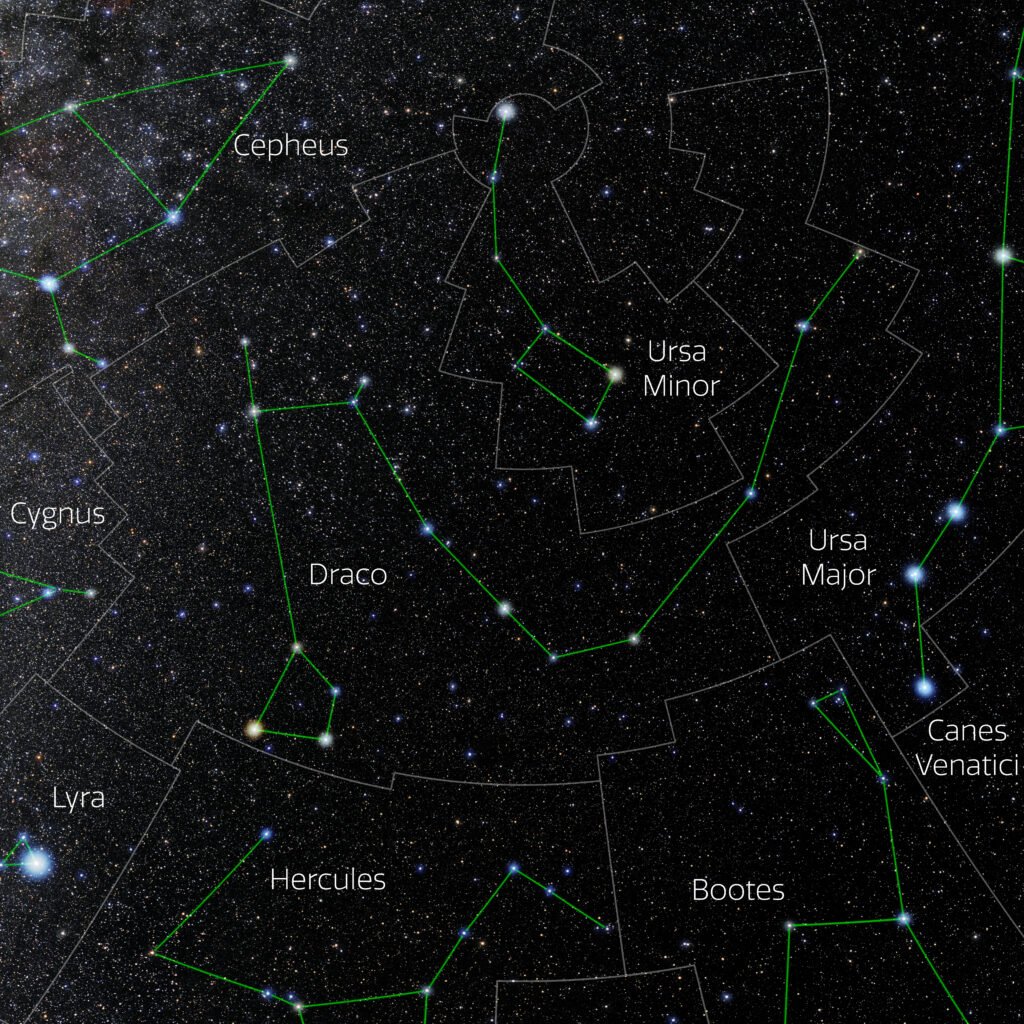

The Constellation Connection: Draco in the Sky

There’s another interpretation that believes the mound was designed to align with the constellation Draco, which would be a type of celestial calendar – the star Thuban, also known as α-Draconis, is positioned precisely at the center of the first serpentine fold of the body just below the head. This connection to the dragon constellation adds another layer of astronomical sophistication to the Serpent’s design. Thuban was the pole star around 3000 BC, though this would predate all current theories about the Serpent’s construction. However, the star would still have been visible and significant to later astronomers. This stellar alignment suggests the builders possessed knowledge not just of solar and lunar cycles, but of stellar positions and movements across centuries. These astronomical alignments put Great Serpent Mound with other fascinating ancient works like Stonehenge and the Moai in Easter Island. The precision required to align an earthwork with specific stars demonstrates a level of astronomical knowledge that rivals any ancient civilization.

Sacred Geography: Why This Spot Matters

Serpent Mound sits on the edge of a meteorite impact crater, and the serpent itself is between 19 and 25 feet wide and rises around 3 feet from the surrounding landscape, with its head formed by a rock cliff overhanging a nearby creek. The builders didn’t just randomly choose this location – they selected it for its unique geological and astronomical properties. Serpent Mound lies on a plateau overlooking the valley of Brush Creek, with the mouth of the serpent opening onto a prominent oval-shaped mound, which is believed to have religious or ceremonial significance. The elevated position provides clear sightlines to the horizon in all directions, essential for astronomical observations. Along the drive to Serpent Mound, the leading edge of the Appalachian Plateau brings fundamental changes in geology, ecology, flora, and fauna – many of Ancient Ohio’s greatest earthen monuments are clustered along this ecological seam, where the abundance of multiple landscapes could be combined and celebrated. This geographical transition zone may have held special spiritual significance, representing a boundary between different worlds or states of being.

Engineering Marvel: Construction Without Modern Tools

Like the mound in Cahokia, the Serpent Mound would have been built by hand basket by basket without the aid of metal digging tools. Yellowish clay and ash make up the main constituents of the mound, with a layer of rocks and soil reinforcing the outer layer. The logistics of moving thousands of tons of earth by hand represents an extraordinary community effort that would have required hundreds of workers and careful planning. It took a lot of effort to build, likely being done one bucket of earth at a time, and there was certainly something significant about positioning the snake to meet the sun. The design was laid out all at once, with a layer of clay and ash, and reinforced with stones – the genius of its designers remains apparent: this blend of beauty, familiarity, abstraction, power, precision, and mystery make Ohio’s Serpent Mound one of the great, iconic images for all of human antiquity. This wasn’t just physical labor – it required sophisticated surveying techniques to ensure astronomical alignments remained accurate across the entire 1,300-foot length.

Indigenous Voices: Reclaiming the Narrative

The Shawnee have a tradition of a female creator with many of the characteristics of First Woman and still have amongst their traditional, religious community a Snake Clan, which speaks powerfully to the importance and durability of the serpent in at least one modern-era Shawnee traditional community. The Shawnee people were removed in eighteen thirty during the Indian Removal Act and moved to Oklahoma. This is the first time they’ve been officially invited to Serpent Mound by any of the entities that have managed it – recently, the Ohio History Connection took over direct management and extended this official invitation to the Shawnee tribe to come back and talk about their connection to that place. For the Shawnee, the Serpent represents more than archaeological curiosity – it’s a connection to ancestral homelands and spiritual traditions. Across different tribes, serpents are largely connected to the creation of the world. As one speaker said during recent solstice presentations: “Let’s be absolutely clear. At the heart of these myths and fantastic stories is the racist notion that American Indians were too stupid to have built something so wonderful.”

Fighting Fringe Theories: Aliens, Giants, and Other Nonsense

There is absolutely no evidence aliens have been involved in Serpent Mound – it was built by American Indian people. Despite overwhelming archaeological evidence, the Serpent has attracted numerous fringe theories that diminish the achievements of indigenous peoples. Some people believe that somehow prehistoric giants created the mounds, while others have forwarded the narrative that it was aliens from another planet that came to the area to seek fuel that was available nearby.