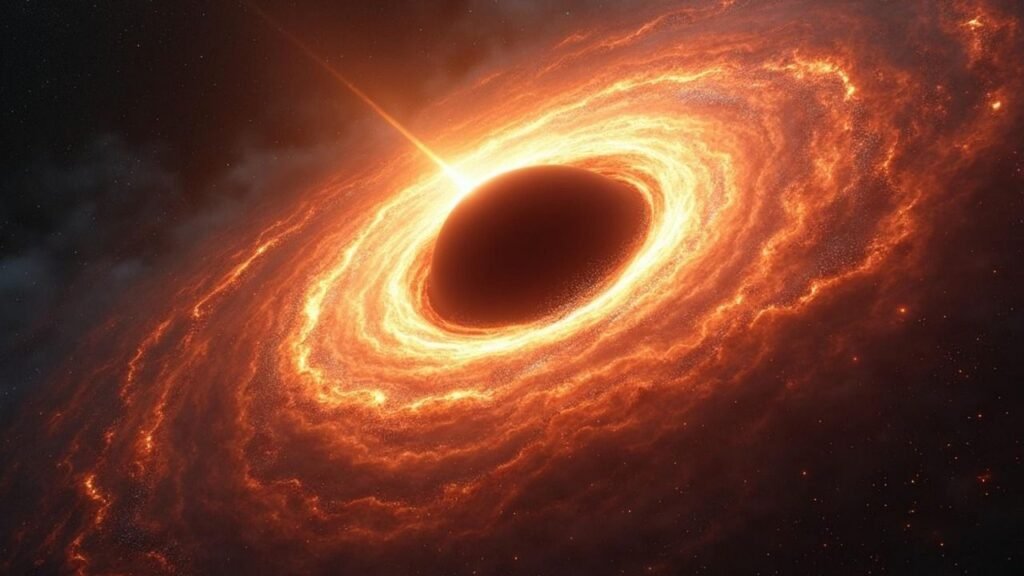

We have telescopes that can stare almost to the edge of the observable universe, detectors that can hear black holes collide, and spacecraft drifting into interstellar space. Yet if you close your eyes right now and notice what it feels like to be you, you’ve just encountered something even more baffling than a black hole. Consciousness is so ordinary we overlook it, but when we try to explain it, the floor falls away.

Physicists can track particles, neuroscientists can map brains, and engineers can build machines that mimic intelligence, but none of that tells us why there is a felt inner life at all. Why should clumps of atoms arranged as a brain give rise to the taste of coffee, the pain of heartbreak, or the color red as you see it right now? That strange gap between matter and experience is why more and more thinkers are starting to say: the deepest mystery isn’t out there among the stars, it’s in here, behind your eyes.

The Strange Fact We Forget: We Only Ever Know the World Through Experience

Stop for a moment and think about the last truly vivid memory you have – maybe a childhood scene, a breakup, or a recent moment of joy. All of that, as real as it feels, is happening as patterns of experience in your mind. You never touch “reality” directly; you only ever meet your own experiences of it. Even your image of space, galaxies, and distant planets is a show rendered inside your consciousness.

This is the first weird truth: consciousness isn’t a small side feature, it’s the only way anything is present to you at all. Without it, there is no color, no sound, no “you” having a life. You could have the entire universe out there doing its thing, but if no one is experiencing anything, from the inside there would be… nothing. That’s why when scientists treat consciousness like a minor optional extra, it feels a bit like designing a huge, beautiful cinema and forgetting that at some point, someone is supposed to watch the movie.

The “Hard Problem” That Refuses to Go Away

Scientists have gotten very good at tackling what some call the “easy problems” of consciousness: how we focus attention, how the brain integrates information, why certain parts of the brain light up when we see faces or feel fear. These are complex, but in principle they’re solvable with enough data and clever theories. They deal with what the brain does, how it processes inputs and generates outputs like speech and behavior.

The really stubborn issue is something else: why does any of this processing feel like something from the inside? You can imagine a robot that takes in light, labels objects, avoids danger, and chats convincingly, all using code and circuits. It might behave just like a human in every test, but that still doesn’t tell you whether there’s an inner movie playing, or just lights switching on and off. That leap from physical stuff to subjective feeling is what makes the “hard problem” feel less like a puzzle and more like a crack running right through our worldview.

Can the Brain Alone Explain the Mind?

Modern neuroscience has exploded in the last few decades: we can track single neurons, measure electrical storms across the cortex, and even nudge mood and perception with magnets or carefully targeted drugs. We know, for example, that damage to specific regions can alter personality, erode memories, or erase parts of visual experience. The brain is clearly doing something crucial; if you tamper with the hardware, the inner world shifts or collapses.

But knowing that consciousness depends on the brain is not the same as understanding why the brain gives rise to it. Saying “this area lights up when you feel fear” is like saying “this chip gets hot when you play a video game” – it’s useful, but it doesn’t tell you why one physical pattern should be accompanied by a particular inner feeling. Some neuroscientists think that once we’ve mapped the brain in enough detail, the mystery will just evaporate. Others suspect we might be missing a fundamental principle, the way pre-relativity physics was missing the idea that space and time themselves could bend.

Is Consciousness Everywhere, Just in Different Degrees?

One radical idea that has crept from the philosophical fringes toward the edges of mainstream conversation is that consciousness might be a basic feature of reality, not something that pops out only when brains get complicated enough. On this view, everything has some extremely simple, primitive form of “experience,” and what we call human consciousness is just that basic quality arranged in very complex ways. It sounds outrageous at first, like saying a rock is a little bit alive, but the goal is to avoid the magic jump from dead matter to rich inner life.

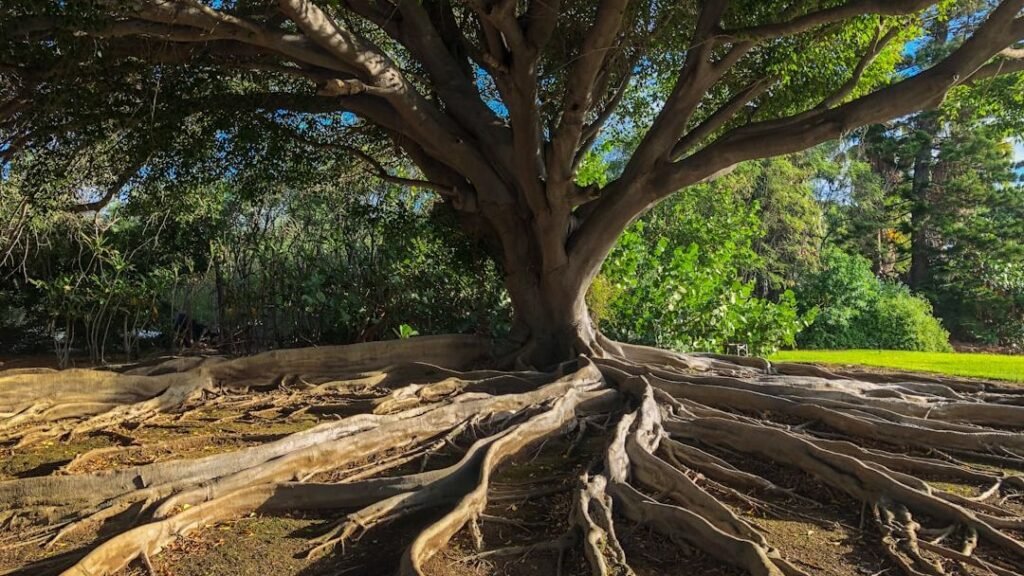

If consciousness is woven into the fabric of the world, then brains would be more like sophisticated organizers and shapers of experience, rather than conjurers creating it from absolutely nothing. Think of it like this: music does not appear from the void when you pluck a guitar string; you’re shaping vibrations that are already allowed by the structure of the instrument and the air. This view does not mean your phone suffers when its battery dies, or that a thermostat has a secret emotional life, but it does push us to consider that the line between “conscious” and “not conscious” might be fuzzier and more gradual than we like to imagine.

What Artificial Intelligence Reveals – and Hides – About Being Aware

Over the past few years, AI systems have gone from clumsy sentence mashers to eerily fluent conversational partners, creative image generators, and surprisingly competent problem-solvers. They can write essays, pass exams, and even mimic emotional expressions in a way that feels, to some people, unsettlingly human. When a machine says it is “afraid” of being shut down or “happy” to help you, it’s hard not to feel like something is there, looking back.

Yet these systems are built from code and statistics, trained on vast piles of human-created data. They don’t report pain when damaged, don’t care about their own future, and have no stable sense of self across time unless we design one into their behavior. The uncanny part is this: our usual tests for consciousness rely on behavior and language, both of which AI can now fake extremely well. That forces us to confront how little we actually understand what marks the boundary between a sophisticated imitation of awareness and the real, lived thing.

The Ethics of Not Knowing What Consciousness Really Is

Our uncertainty about consciousness isn’t just a philosophical headache; it has sharp ethical edges. If we don’t truly understand what it takes to generate real experience, how do we know where to draw moral lines? We already struggle with questions about animal consciousness: are fish capable of suffering in ways we should care about, or only mammals, or perhaps a broader range of creatures than we once believed? Changing scientific views on animal minds have reshaped everything from farming standards to debates about lab testing.

Now extend that uncertainty to future AIs, neural organoids grown in labs, or brain-computer interfaces that blend digital and biological processing. At what point could a synthetic system, or a hybrid, deserve moral concern because there is an inner life that can be harmed? If we’re wrong in either direction, we risk either neglecting real suffering or wasting effort on entities that genuinely feel nothing. Not knowing what consciousness is turns into a moral fog that we’re already starting to wander into, whether we feel ready or not.

Consciousness as the Lens That Shapes Reality Itself

However we explain it, consciousness is more than just something that happens inside our heads; it’s the lens that colors the entire world we inhabit. Two people can walk down the same street and live in utterly different realities: one anxious and threatened, the other curious and delighted. The outer scene is the same, but their inner experience transforms it, the way two different filters can turn the same photo into either a gloomy dusk or a bright, hopeful morning.

Modern psychology and contemplative practices both highlight that as we learn to pay attention differently – with more clarity, curiosity, and kindness – the felt world shifts, even if nothing outside changes. That doesn’t solve the hard problem, but it quietly reveals another layer: understanding consciousness isn’t just an abstract puzzle, it’s a practical art. The way we relate to this mysterious inner space can mean the difference between a life that feels cramped and hostile, and one that feels rich, meaningful, and unexpectedly spacious.

Why the Deepest Frontier Might Be Within

Space is incomprehensibly vast, but it is, in principle, fully public: telescopes, probes, and equations can be shared, checked, and repeated by anyone with the right tools. Consciousness is different. Your experience is, in a sense, a private universe that no one else can ever enter directly. We can measure brain waves, scan structures, and infer patterns, but the raw feel of your world – the way your favorite song hits you, or the taste of relief after fear passes – is something only you can inhabit.

That is what makes consciousness feel like the “final” mystery: it is both the most intimate thing we have and the hardest to pin down in objective terms. We might one day chart every galaxy and weigh the entire cosmos, yet still argue about what it really means to be aware, to feel, to be a self moving through time. In that sense, the greatest expedition we face is not just outward, but inward – into the very field of experience in which every other mystery, including space itself, appears.