Some forms of life laugh in the face of what we call “impossible.” While we worry about sunscreen and seatbelts, there are tiny creatures chilling near boiling acid, floating between ice crystals, or silently feeding on radiation in old nuclear reactors. Their existence doesn’t just stretch our imagination; it forces us to rewrite the rules of biology itself.

These extreme organisms, known as extremophiles, are like nature’s daredevils. They survive where everything else dies, from scalding volcanic vents to deep frozen deserts and even outer space. Learning how they manage this doesn’t just satisfy curiosity – it shapes medicine, space exploration, energy, and even how we think life might look on other worlds.

Heat Lovers: Life in Boiling Water

Can you imagine a creature that feels most comfortable in water hot enough to cook your dinner? Thermophiles and hyperthermophiles thrive in temperatures that would destroy most cells in seconds, sometimes close to the boiling point of water. They live in hot springs, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, and even inside industrial machinery where scalding fluids are pumped around.

Their secret is tough, highly stable proteins and cell membranes that don’t fall apart when heated. Enzymes from these organisms are now used in everyday lab tests and DNA technology because they stay active at high temperatures where normal enzymes fail. I still remember the first time I saw a photo of bacteria happily living in a bright blue-yellow Yellowstone hot spring – it felt like a slap in the face to everything I thought I understood about “too hot to live.”

Cold Survivors: Thriving in Deep Freeze

At the other extreme, psychrophiles call freezing temperatures home, flourishing in polar oceans, subglacial lakes in Antarctica, and deep sea environments where sunlight never reaches. Instead of being killed by ice, they’ve learned to work around it, using proteins that act like natural antifreeze and flexible cell membranes that stay soft instead of turning brittle. If heat lovers are fiery daredevils, cold lovers are patient survivors, quietly getting on with life in slow motion.

These organisms grow slowly, but they never truly stop, even just below the freezing point of water. Their tricks are inspiring better food preservation methods, enzymes that work in cold-water detergents, and even ideas about what life might look like under the icy shells of moons like Europa or Enceladus. It’s wild to think that a slime of cold-loving microbes sitting under Antarctic ice right now might resemble something living under an alien ocean light-years away.

Radiation Eaters: When Nuclear Waste Becomes Habitat

Radiation is one of the most destructive forces for living cells, shredding DNA and causing deadly mutations. Yet some microorganisms, especially the famous radiation-resistant bacteria like those in the genus Deinococcus, can survive doses of radiation that would obliterate humans many thousands of times over. They don’t just endure it; they repair the damage with astonishing efficiency, stitching their shattered DNA back together like a microscopic mechanic fixing a wrecked car.

Some of these organisms have been found in places touched by nuclear accidents, thriving in areas we consider dangerously contaminated. Their supercharged DNA repair systems and protective molecules are inspiring research in cancer treatment, radiation protection for astronauts, and long-term storage of nuclear waste. When you realize something can happily live in what we label “uninhabitable,” it makes our old maps of safe versus deadly environments feel embarrassingly naive.

Salt Addicts: Life in Toxic Brine

Most living things shrivel up and die in very salty environments because salt drags water out of their cells. Halophiles flip that script and treat concentrated salt as home sweet home. You’ll find them in places like the Dead Sea, salt flats, brine pools, and salt-saturated ponds that look more like pickling jars than ecosystems. To them, what we’d consider a toxic brine is more like a cozy warm bath.

These organisms adjust by stockpiling compatible salts and protective molecules inside their cells, carefully balancing the crushing osmotic pressure. Some even contain pigments that give salt lakes a stunning pink or red color, turning entire landscapes into surreal watercolor paintings. Their unique biochemistry is being explored for food preservation, stable enzymes that work in salty industrial processes, and even colorants and sunscreens that can handle serious environmental stress.

Pressure Defiers: Life in the Crushing Deep

In the deep ocean trenches, the weight of the water above creates pressures hundreds of times greater than what we experience at the surface. For us, that kind of pressure would cause catastrophic damage, but for barophiles (also called piezophiles), it’s just normal daily life. These microbes and sometimes even small animals live in the quiet, pitch-black world of the deep sea, where sunlight never arrives and the pressure could crush a submarine like a soda can.

They survive with ultra-flexible cell membranes, specially adapted proteins, and pressure-tuned metabolisms that fall apart if you try to bring them to the surface. Studying them is hard because the moment you haul them up, you remove the very conditions they need to stay alive. Still, what we’ve learned from them is changing how we think about the limits of life on ocean worlds and driving new ideas for high-pressure chemistry, food sterilization, and long-term storage technologies.

Tardigrades: The Tiny Tanks of the Micro World

No list of extreme organisms is complete without mentioning tardigrades, the famously tough “water bears.” These microscopic animals have become pop-culture icons of resilience because they can survive extreme heat, deep cold, intense radiation, high pressure, and even the vacuum of outer space for limited periods. When conditions get too harsh, they enter a dried-out, almost glass-like state called a tun, shutting down nearly all activity and waiting, sometimes for years, until things improve.

In this suspended state, their DNA and proteins are protected by unique sugars and structural molecules that act like a biological bubble wrap. When water returns, they rehydrate and wake back up, often as if nothing happened. Seeing something so tiny shrug off environments that would kill us instantly is humbling and a bit unsettling, like realizing the toughest survivor in the room is a speck you need a microscope to see. Researchers are racing to copy their tricks to improve vaccines, dry storage of biological materials, and maybe even long-distance space travel tech.

Alien Clues: What Extremophiles Tell Us About Life in the Universe

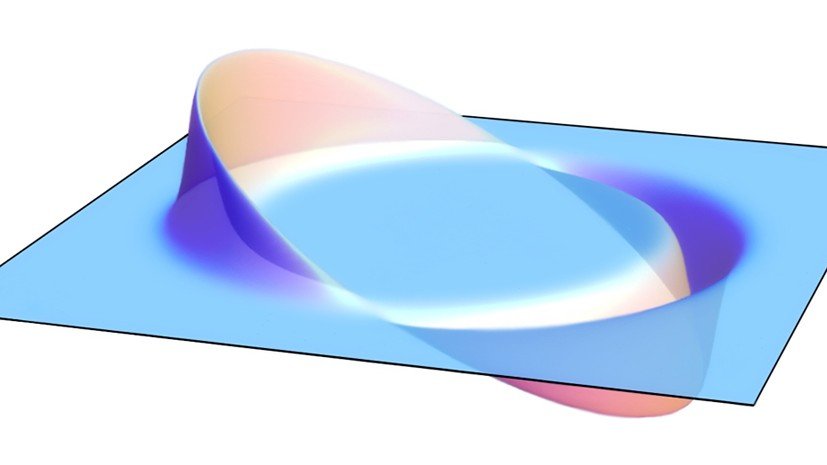

For a long time, we assumed life needed mild, Earth-like conditions: moderate temperatures, gentle radiation, and chemistry that looked a lot like ours on the surface. Extremophiles have wrecked that comfortable assumption. If life can thrive in boiling acid, frozen oceans, toxic brines, and radiation-soaked ruins here on Earth, then planets and moons we once dismissed as barren suddenly look far more promising.

Astrobiologists now actively use extremophiles as guides, asking where on Mars salty brines might briefly appear, or how a deep ocean under Europa’s ice could support chemosynthetic microbes like those at Earth’s hydrothermal vents. Even the idea of dormant or hidden life clinging on in apparently dead environments seems less far-fetched when you think of tardigrades quietly waiting out disaster in tiny cryptobiotic capsules. By studying these extraordinary organisms, we’re not just learning how life bends the rules; we’re expanding our sense of where, and how, life could exist beyond our planet.

Conclusion: Redefining What “Alive” Can Mean

Extreme organisms force us to confront a simple but uncomfortable idea: our everyday experience is not the standard for life, it is just one narrow slice of what’s possible. From heat-loving microbes in volcanic vents to water bears sleeping through cosmic-level stress, these beings show that life is both tougher and stranger than most of us were ever taught. Their resilience is not just a curiosity; it drives new technologies, new medical ideas, and a new map of where we might search for life beyond Earth.

In a way, extremophiles hold up a mirror and ask whether we’ve been too quick to label places, situations, or even ideas as hopeless. If a microbe can learn to call a nuclear waste pool home, maybe our sense of what’s “unlivable” – literally and metaphorically – needs updating. The real question lingering after meeting these organisms is simple and unsettling: if life can exist there, where else might it already be hiding?