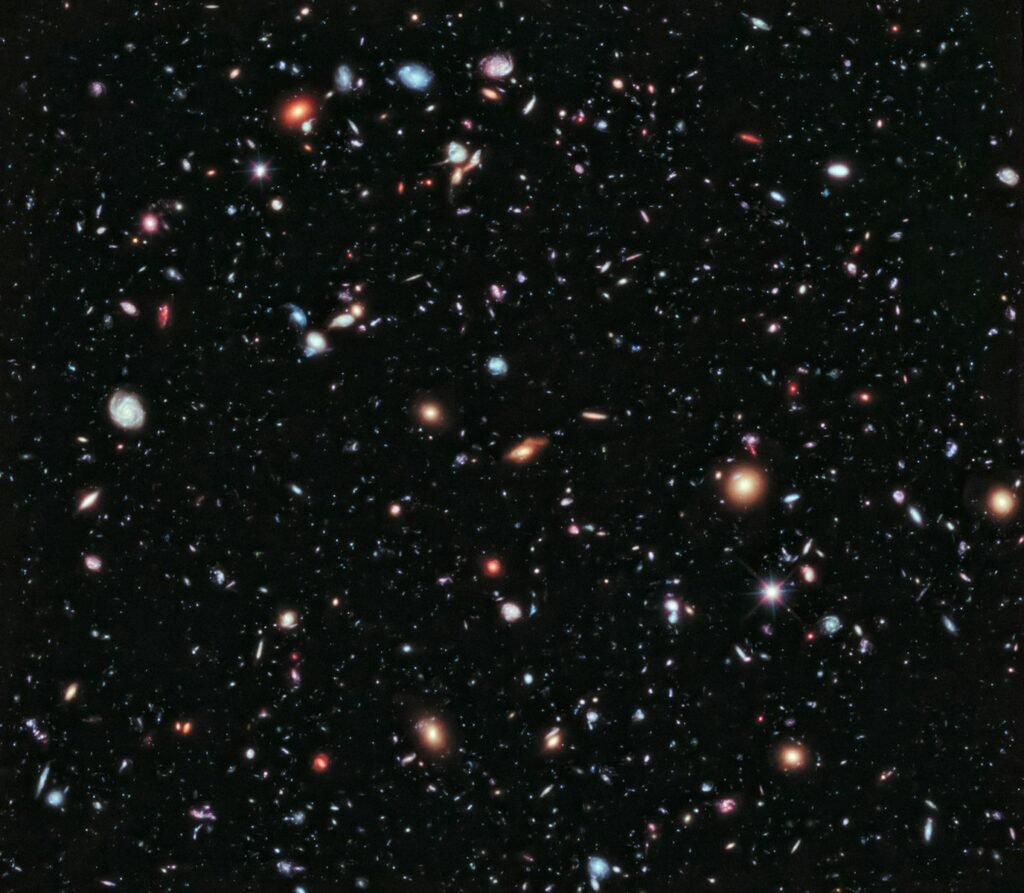

Somewhere between the galaxies we can see and the void we can’t quite grasp lies a missing ingredient that refuses to reveal itself. Astronomers call it dark matter, and without it, the universe as we know it simply does not add up. Galaxies spin too fast, clusters of galaxies cling together too tightly, and the cosmic web looks far too structured for visible matter alone. Yet after decades of searching, no one has directly seen or touched this elusive substance. As new telescopes, detectors, and data-driven tools come online, scientists are starting to feel that the universe’s invisible scaffolding might finally be within reach.

The Hidden Clues in a Turbulent Cosmos

It sounds almost like a cosmic prank: roughly about five sixths of all matter in the universe appears to be invisible. Astronomers infer its presence not by what it shines, but by how it tugs. When they measure how fast stars orbit in the outer regions of galaxies, they find those stars moving so quickly that, if only visible matter were present, the galaxies should fly apart. Instead, they hold together, as if embedded in vast, unseen halos of extra mass. The mismatch between what telescopes see and what gravity demands is the first smoking gun for dark matter.

Beyond individual galaxies, the pattern continues on grander scales. Massive clusters of galaxies bend and distort the light of more distant objects behind them, acting like giant natural lenses in space. By mapping these warped arcs of light, astronomers can reconstruct where mass must be hiding, and the resulting maps reveal far more matter than any census of stars and gas can explain. Even the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, the cosmic microwave background, carries subtle ripples that encode how much dark matter must have been present in the early universe. Taken together, these clues form a remarkably consistent story: something invisible shaped the cosmos from its earliest moments, and it is still quietly steering its evolution today.

From Ancient Skies to Precision Cosmology

Humans have stared at the night sky for tens of thousands of years, but the idea that most of the universe is invisible is surprisingly recent. Early astronomers assumed that the stars they saw were the main ingredients of the cosmos, a kind of sparkling shell wrapped around Earth. Even as telescopes grew more powerful and astronomers realized that the Milky Way was just one galaxy among many, the working assumption stayed the same: what you see is mostly what you get. It was only in the twentieth century that hints of something more began to creep into the data.

By the 1930s, measurements of galaxy clusters suggested that visible galaxies did not provide nearly enough mass to keep those clusters bound, but the idea was too radical to fully take hold. Decades later, astronomer Vera Rubin’s careful observations of spiral galaxies pushed the field past the point of denial. She found that stars far from galactic centers were orbiting almost as fast as those closer in, defying expectations based on visible mass alone. Fast-forward to the present, and dark matter is now woven into what cosmologists call the standard model of cosmology, a framework that explains how the universe expanded, cooled, and clumped into today’s rich tapestry of galaxies and clusters.

What Dark Matter Might Be Made Of

Knowing that dark matter exists and knowing what it is are very different challenges. The leading idea for many years has been that dark matter consists of unfamiliar particles, different from the protons and electrons that build ordinary matter. These hypothetical particles would interact very weakly with light and normal matter, which is why we do not see or feel them directly. Physicists have proposed entire families of such particles, from so-called weakly interacting massive particles to ultra-light axions that behave more like a field than a swarm of distinct particles. The zoo of possibilities is vast, and nature has been slow to reveal which, if any, of these guesses is correct.

To narrow things down, scientists have built exquisitely sensitive detectors in deep underground laboratories, hoping to catch the rare collision between a dark matter particle and an atomic nucleus. Other teams look to powerful particle accelerators to see whether high-energy collisions can momentarily create dark matter that slips away from detectors, leaving missing energy as a telltale sign. Meanwhile, astronomers use space and ground-based telescopes to search for faint signals that might arise if dark matter particles occasionally interact with each other. The fact that no single approach has yet delivered a clear, definitive detection has forced the community to refine, expand, and sometimes abandon long-cherished models.

The Universe as an Invisible Web

If you could somehow turn off the stars and only see gravity, the universe would look like a giant three-dimensional spiderweb. Dark matter forms the thick strands and knots of that web, while galaxies are like dewdrops that gather where the strands intersect. Computer simulations of cosmic evolution, fed with the right amount of dark matter, reproduce this structure with striking accuracy. Where dark matter is dense, ordinary gas falls in, cools, and eventually forms stars and galaxies. Where dark matter is sparse, cosmic voids open up like vast deserts of almost nothingness.

Modern sky surveys are now mapping this web in unprecedented detail. Instruments that measure the subtle distortions in the shapes of millions of distant galaxies can infer how dark matter is distributed along the line of sight, a technique known as weak gravitational lensing. New telescopes, including those dedicated to the so-called dark energy and dark matter missions, are generating petabytes of data that can be compared to simulations. These comparisons help test different dark matter scenarios; for example, whether dark matter is perfectly cold and collisionless or slightly warm and self-interacting. Every mismatch between simulation and observation is a potential clue, a nudge toward a better understanding of what the invisible scaffolding is actually made of.

Why It Matters: The Stakes of the Invisible

It is fair to ask why this matters to anyone who is not a cosmologist staring at simulation plots. One answer is that dark matter is not just a cosmic curiosity; it is a missing piece in our broader understanding of what reality is made of. Our best theory of particle physics, the Standard Model, has been enormously successful in predicting and explaining known particles and forces, yet it has no slot for dark matter. That suggests there is a deeper layer to nature’s rulebook that we have not yet uncovered. Whenever physics has bumped against such a limit before, new discoveries have eventually reshaped technology and everyday life in ways that were impossible to predict at the time.

There is also a philosophical charge to the whole enterprise. The idea that the vast majority of matter in the universe is something entirely different from the matter that makes our bodies, our cities, and our planet is humbling. It challenges our intuition that what we see is all there is and that human-scale experience captures the essence of reality. Understanding dark matter could help settle long-running questions about how galaxies like the Milky Way formed and why our local cosmic environment looks the way it does. In that sense, dark matter research is a kind of cosmic genealogy, tracing the hidden branches of our universe’s family tree.

Global Teams, Deep Mines, and Sky-Spanning Surveys

The hunt for dark matter is surprisingly down to Earth. Some of the most sensitive experiments sit in old mines or beneath mountains, shielded from the constant drizzle of cosmic rays that rain down through the atmosphere. In these underground labs, tanks of liquid xenon or arrays of cryogenic crystals wait in the dark, hoping for the faintest nudge from a passing dark matter particle. Scientists from many countries collaborate on these projects, pooling expertise in engineering, particle physics, and data analysis. For all their complexity, these detectors are, at heart, carefully tuned ears pressed against the fabric of space, listening for whispers.

On the other side of the hunt are giant telescopes and survey missions that scan huge swaths of sky night after night. Facilities in Chile, Hawaii, South Africa, the Canary Islands, and beyond are all contributing pieces to this global puzzle. Space-based observatories add another vantage point, free from atmospheric distortion, especially in wavelengths that do not reach the ground. Data from all these instruments are shared widely, and teams often compete and cooperate at the same time, racing to interpret subtle patterns. This international, multi-pronged approach is a reminder that cracking the dark matter mystery is not the work of a lone genius, but of a worldwide scientific community slowly tightening the net around an invisible quarry.

Controversies, Alternatives, and the Value of Doubt

Not everyone is convinced that dark matter is made of new particles waiting to be discovered. A vocal minority of physicists argues that the problem lies not in missing matter but in our understanding of gravity itself. According to these researchers, the laws that describe how gravity behaves on Earth and in the solar system might need to be modified on galactic and cosmic scales. Ideas like modified Newtonian dynamics and other alternative gravity theories attempt to explain galaxy rotations and other phenomena without invoking an invisible substance. So far, these approaches struggle to match the full range of cosmological observations, but they continue to spark vigorous debate.

This tension is healthy, if sometimes messy. Science advances not just through confirming ideas, but by confronting stubborn anomalies and listening seriously to dissenting voices. Personally, I find it oddly reassuring that dark matter has not yet been cleanly detected; it means we are still in the thick of discovery, not just tidying up details. In my own work following these developments, it sometimes feels like watching a detective show where every new clue deepens the mystery rather than resolves it. That sense of open-endedness is frustrating for those craving closure, but it is also a sign that something genuinely profound is at stake.

The Future Landscape: New Eyes and Bolder Experiments

The next decade is poised to be a stress test for dark matter theories. New observatories designed to map billions of galaxies will track how cosmic structures grow over time with unprecedented precision. If dark matter behaves even slightly differently from the simplest models, those differences could show up in how galaxy clusters form, merge, and bend light. At the same time, upgraded underground detectors will be sensitive to much rarer and fainter interactions than ever before. Even the absence of a signal in these experiments will not be a failure; it will slash away whole swaths of theoretical possibilities and push physicists toward new ideas.

On the theoretical side, some researchers are exploring more exotic scenarios, from mixtures of different dark matter species to models where dark matter has its own hidden forces. Others are looking for ways to connect dark matter with puzzles in other areas of physics, such as the nature of neutrinos or the origin of cosmic inflation. Computational advances mean that simulations of the universe can now track ever more detail, letting scientists test how tiny tweaks in dark matter properties would ripple across billions of years. There is a real possibility that the decisive breakthrough will come not from a single dramatic detection, but from a convergence of hints across many methods. If that happens, we might look back on this period as the last stretch of darkness before the outline of the invisible cosmos finally came into focus.

How Readers Can Engage With the Invisible Universe

Even if you never set foot in an underground lab or operate a telescope, you can still be part of the story unfolding around dark matter. One simple step is to stay curious and seek out reliable science reporting rather than settling for sensational headlines. Many dark matter experiments and observatories maintain public outreach pages, where you can follow live data releases, watch talks, or explore interactive visualizations of the cosmic web. Supporting science literacy in your community, whether by visiting local planetariums, attending public lectures, or encouraging kids’ questions about space, helps create the social environment in which ambitious research can thrive. Curiosity is contagious, and in a field built on almost invisible clues, an engaged public is more important than it might seem.

There are also more concrete ways to contribute. Some projects open portions of their data to citizen scientists, who help classify galaxies or spot unusual patterns that algorithms might miss. Public funding and philanthropic support for basic research, often influenced by voter priorities and cultural attitudes toward science, shape which big bets society is willing to take. Even conversations about what mysteries we choose to pursue can nudge policy makers toward sustained investment in fundamental physics. The universe’s invisible scaffolding may feel remote from daily life, but the decision to search for it is a very human one, grounded in collective choices about what kinds of knowledge we value.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.