If you could see Earth’s magnetic field with your own eyes, our planet would look like a glowing blue comet, wrapped in invisible lines of force stretching far into space. It silently deflects deadly solar radiation and high‑energy particles every second of every day, yet most of us go through life barely knowing it’s there. The truly unsettling part is that scientists, with all our satellites and supercomputers, still don’t fully understand how stable this shield really is or how it will behave in the future.

I remember the first time I saw an animation of the magnetic field wobbling and rippling as a solar storm hit it; it felt less like watching a solid wall and more like watching a living, breathing jellyfish trying to hold its shape in rough seas. That’s when it hit me: we’re depending on something we can’t touch, can’t see, and still can’t predict with full confidence. For a planet‑scale life support system, that’s both awe‑inspiring and just a little terrifying.

The Invisible Armor Wrapped Around Our Planet

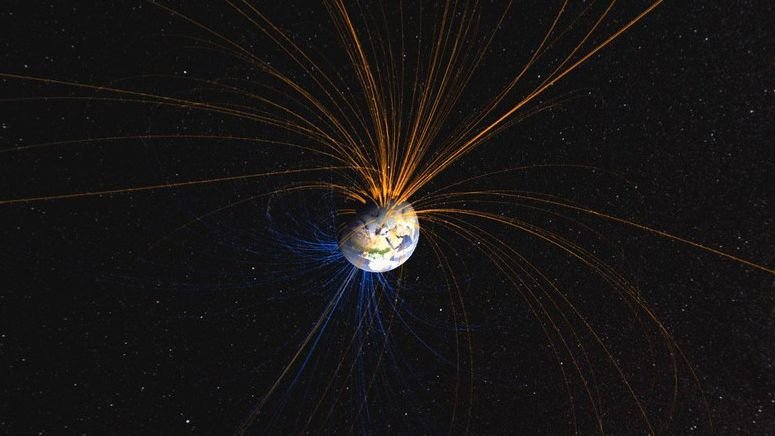

Picture Earth floating in a constant storm of charged particles streaming from the Sun at astonishing speeds; without protection, our atmosphere would slowly erode away, and life as we know it would be in serious trouble. Earth’s magnetic field acts like an invisible armor, redirecting many of these particles around our planet and trapping others in vast donut‑shaped zones known as the Van Allen radiation belts. It’s not a perfect shield, more like a flexible forcefield that takes the hit so our air, oceans, and DNA are not constantly battered.

From space, instruments detect the magnetic field forming a bubble called the magnetosphere, which extends tens of thousands of kilometers outward on the day side and stretches into a huge tail on the night side. That tail can reach far beyond the orbit of the Moon during calmer conditions. Inside this magnetic cocoon, satellites, astronauts, and all life on the surface exist in a kind of protected pocket. We don’t feel the field like we feel gravity, but it’s quietly shaping the space environment around us every moment.

A Churning Metal Ocean Deep Below Your Feet

For something so massive, the source of Earth’s magnetic field is hidden in a place we will likely never visit: the outer core, roughly three thousand kilometers below the surface. There, an ocean of molten iron and nickel swirls and flows, conducting electricity and generating magnetic fields in a process known as the geodynamo. You can imagine it a bit like a colossal, self‑sustaining electric generator, except instead of well‑machined coils and magnets, we have super‑hot liquid metal moving under intense pressure and rotation.

Convection in this metallic ocean is driven by heat escaping from the deeper core and the slow crystallization of the solid inner core, which releases lighter elements upward. As Earth spins, these flows twist and align, creating large‑scale magnetic structures, but the details are maddeningly complex. Supercomputer models can reproduce broad features of the field, yet small changes in the flow can lead to very different outcomes over long timescales. That’s one reason predicting future behavior of the magnetic field is a bit like trying to forecast the weather a thousand years from now.

A Magnetic Field That’s Constantly Moving and Changing

Many people grow up thinking Earth’s magnetic field is stable, like a bar magnet frozen in rock, but in reality it’s restless and always shifting. The magnetic north pole is not fixed at the top of the planet; it wanders, and in recent decades it has been racing from northern Canada toward Siberia at a surprisingly fast pace. That motion has forced aviation authorities and navigational mapmakers to update magnetic reference models more frequently, because runways and navigation systems actually depend on an accurate magnetic north.

On shorter timescales, there are also smaller magnetic “eddies” and patches that drift and evolve around the globe, some strengthening while others weaken. Satellites such as the European Space Agency’s Swarm trio have mapped these changes in remarkable detail, revealing fine‑scale anomalies and fast, wave‑like disturbances rippling through the field. Over centuries and millennia, these patterns add up to big transformations. When scientists compare current measurements to old ship logs and archaeological records, they see a magnetic field that has been anything but calm over Earth’s long history.

The Mystery of Magnetic Reversals and What They Mean

One of the most dramatic, and frankly unsettling, discoveries about Earth’s magnetism is that the field has flipped many times in the past. Polarity reversals mean that if you could hold a compass during those eras, the needle would point roughly toward what we now call south instead of north. These reversals are recorded like magnetic fingerprints in volcanic rocks and seafloor crust, which lock in the direction of the local field as they cool and solidify. By reading these patterns, scientists have reconstructed a history of many switches over tens of millions of years.

These flips do not happen overnight; they likely take hundreds to thousands of years, and the field can become weaker and more chaotic during the transition. Some researchers wonder if the present‑day weakening of parts of the field, especially in regions like the South Atlantic Anomaly, could be an early sign of a larger reorganization. But the timing of reversals appears irregular, and models still can’t predict if another flip is “due.” That uncertainty leaves a big question mark over how such a transition would affect satellites, power grids, and radiation exposure for people at high altitudes.

The South Atlantic Anomaly: A Weak Spot in the Shield

If Earth’s magnetic field is our armor, then the South Atlantic Anomaly is the dent that engineers and space agencies keep worrying about. This region, stretching roughly from South America into the South Atlantic, is where the inner Van Allen belt dips unusually close to the planet. As a result, satellites passing overhead encounter higher levels of energetic particles, which can cause electronic glitches, degraded instruments, or in extreme cases permanent damage. Operators often shut down or harden sensitive equipment when spacecraft cross that zone.

Measurements show that this anomaly has been growing and shifting over the last century or so, and that trend has continued with modern satellite observations. Some scientists think it’s linked to complex structures in the core, where patches of reversed or weakened magnetization deep below Africa may be tugging at the overall field. Others caution that we still don’t fully grasp how these core features evolve. For people on the ground, the anomaly doesn’t cause dramatic everyday effects, but for the growing population of satellites and crewed missions, it’s like a persistent pothole on a very busy orbital highway.

Space Weather, Solar Storms, and a Vulnerable Civilization

The magnetic field doesn’t just passively sit there; it wrestles with the solar wind, and that struggle creates what scientists call space weather. When powerful bursts of particles and magnetic fields blast out of the Sun and slam into Earth’s magnetosphere, they can compress, twist, and reconnect our field lines. That process injects energy into near‑Earth space, triggering auroras at high latitudes that paint the sky with eerie curtains of green and red light. It’s beautiful from the ground, but from a technological standpoint, it can be risky.

Strong geomagnetic storms can induce electrical currents in long conductors like power lines, pipelines, and undersea cables, stressing transformers and other infrastructure. Historical events have already demonstrated that such storms can knock out regional power grids and disrupt radio, GPS, and satellite operations. As our modern world leans ever more heavily on space‑based systems and long‑distance electrical networks, our dependence on the magnetic field’s buffering effect becomes more obvious. We’re learning to monitor and forecast space weather better, but our understanding of how extreme events couple into the core magnetic processes is still incomplete.

Animals, Compasses, and How Life Uses the Field

Long before humans built compasses, other creatures were already using Earth’s magnetic field as a natural GPS. Many migratory birds, sea turtles, some fish, and even certain insects appear to sense the field and use it to navigate across vast distances. Experiments suggest they can detect not only the direction of magnetic north, but also subtle changes in field intensity and angle, giving them a kind of built‑in map. The actual biological “hardware” that does this sensing remains an active area of research, involving ideas from tiny magnetic particles in tissues to quantum effects in specialized proteins.

Humans harnessed the field in a more obvious way with the invention of the magnetic compass, which transformed navigation and trade by allowing sailors to cross oceans with much more confidence. Today, digital compasses in phones, airplanes, and ships still depend on accurate models of the magnetic field to work properly. Changes in the field force periodic updates to those models and even to aviation charts that label runway headings. It’s a quiet reminder that, even in a GPS world, we’re still fundamentally tied to that invisible planetary magnetism humming beneath our feet.

What We Still Don’t Know – and Why It Matters

For all the satellites, observatories, and simulations, we’re still in the early chapters of truly understanding Earth’s magnetic shield. We don’t yet know exactly when or how the next major reversal or major reconfiguration will happen, or how extreme it might be. Our models of the core are limited by the fact that we can’t directly sample it, and lab experiments can only approximate the scorching temperatures and crushing pressures found there. The field we measure at the surface is the end result of a chain of processes extending from the core outward through the mantle, crust, and space environment, and unpacking all of that is a long‑term scientific puzzle.

At the same time, there’s a growing recognition that understanding the magnetic field isn’t some abstract academic exercise. It shapes radiation hazards for astronauts, reliability of satellites and power grids, and even how we design infrastructure for a more space‑dependent civilization. In a way, studying the field forces us to confront how fragile our comfortable technological bubble might be when set against the raw forces of the Sun and Earth’s interior. The magnetic shield has protected life on this planet for billions of years, but we’re only just starting to grasp how dynamic, complex, and unpredictable it really is.