Imagine opening a time capsule buried for over half a billion years, only to find creatures so bizarre, so utterly alien, that you question everything you ever thought you knew about life on Earth. That’s exactly what happened when scientists first cracked open the Burgess Shale—an extraordinary fossil bed hidden high in the Canadian Rockies. The discoveries here didn’t just rewrite the textbooks; they flipped the whole story of evolution on its head and gave us a front-row seat to the moment when nature’s imagination truly ran wild.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

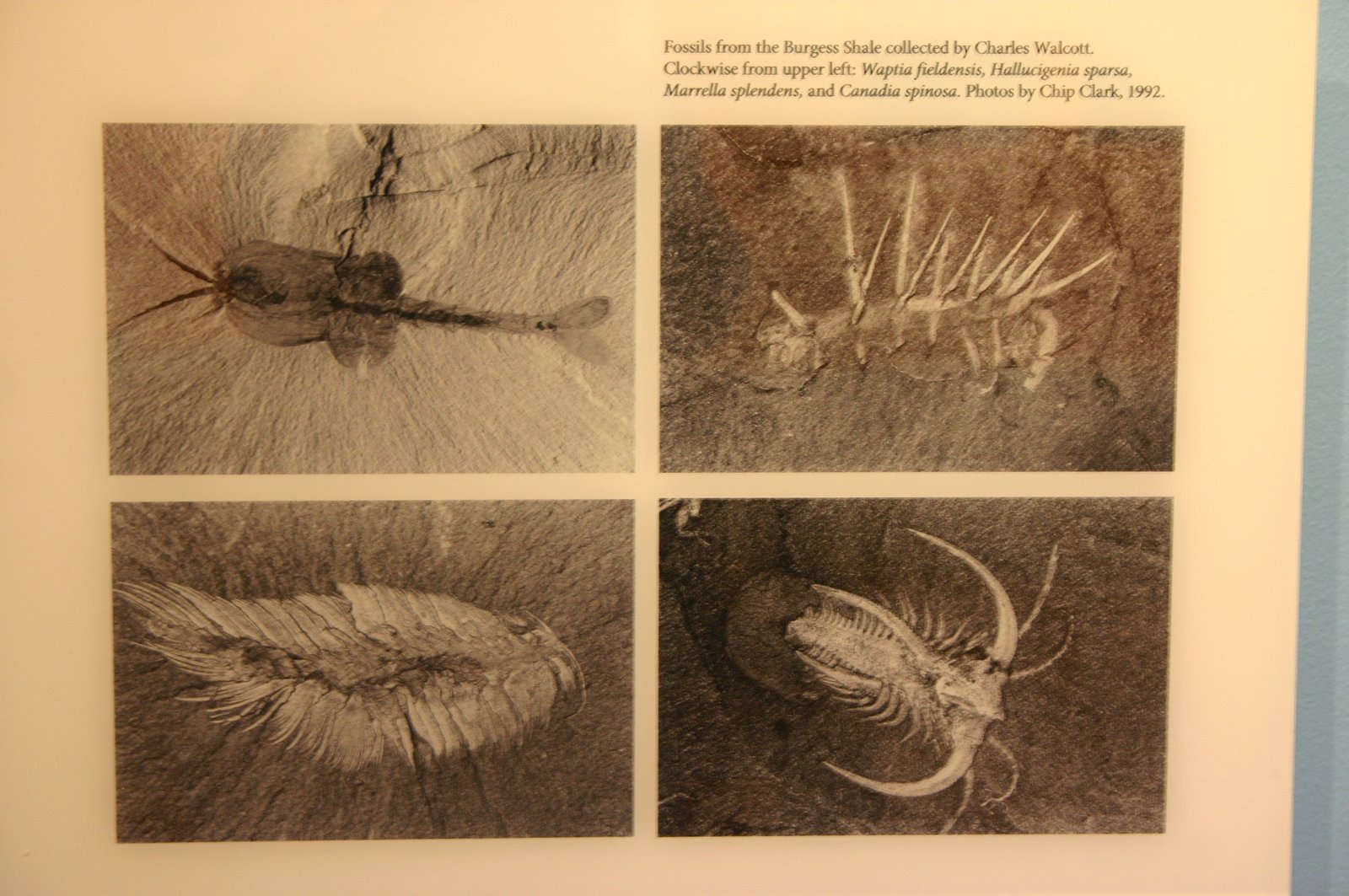

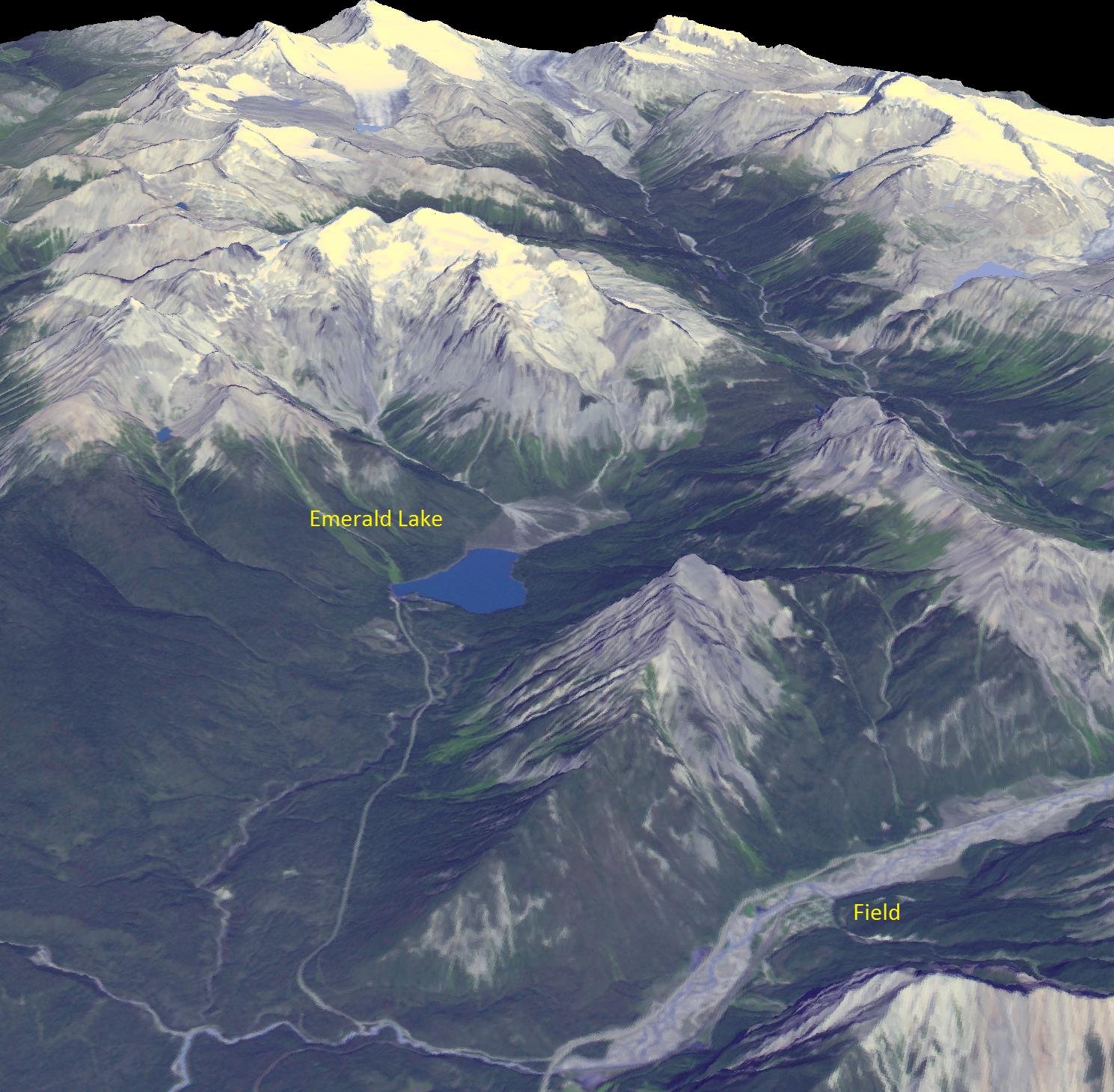

The Burgess Shale was first discovered in 1909 by Charles Doolittle Walcott, a paleontologist with a knack for unearthing the unknown. He stumbled upon this treasure trove of fossils during a hike in the Yoho National Park, British Columbia. What he found was astonishing: layer upon layer of exquisitely preserved ancient sea creatures dating back to the middle Cambrian period, around 508 million years ago. Unlike most fossil sites, the Burgess Shale didn’t just capture bones or shells—it preserved the soft, squishy bits of animals rarely fossilized elsewhere. This meant that even the strangest and most delicate life forms were frozen in time, offering an unprecedented window into the dawn of complex life.

The Cambrian Explosion: Life’s Big Bang

The creatures of the Burgess Shale emerged during one of the most mind-blowing periods in Earth’s history: the Cambrian Explosion. This was a time when life suddenly diversified at a speed that seems almost impossible, with countless new body plans popping up in the blink of a geological eye. Before this era, most life forms were simple and soft-bodied, but the Cambrian marked the rise of animals with hard parts, specialized organs, and complex behaviors. The Burgess Shale captures this evolutionary burst in vivid detail, showing us not only what survived, but also many evolutionary experiments that vanished without a trace.

Walcott’s Legacy and the Forgotten Decades

After Walcott’s initial discovery, he spent years collecting and cataloging thousands of fossils, filling drawers at the Smithsonian with his findings. Yet, for decades, many of the Burgess Shale’s weirdest residents sat largely misunderstood, often forced into familiar modern categories. It wasn’t until the 1970s that a new generation of scientists, armed with fresh ideas and better technology, began to truly appreciate the strangeness and significance of these fossils. Their work revealed a hidden menagerie of creatures that defied classification—and sometimes even logic.

Hallucigenia: The Walking Pipe Cleaner

Among the cast of characters preserved in the Burgess Shale, few are as famous—or as confounding—as Hallucigenia. This spiky, worm-like creature looks like it crawled out of a fever dream, with a row of stilt-like spines on its back and tentacle-like appendages below. For years, scientists couldn’t even agree which way was up, literally reconstructing it upside down in museum displays. Eventually, careful study revealed its true orientation, but Hallucigenia remains a symbol of just how unpredictable and experimental early animal evolution could be.

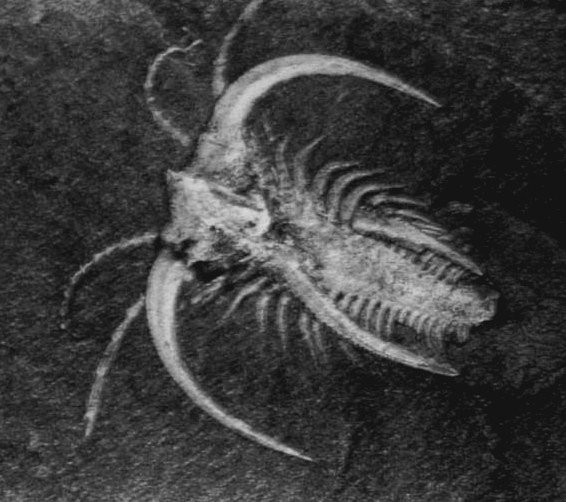

Anomalocaris: The Apex Predator of Its Time

If you could travel back to Cambrian seas, you’d want to watch your fingers around Anomalocaris. This ancient predator was a meter long—enormous for its time—with a segmented body, bizarre compound eyes, and a pair of fearsome, grasping appendages. It sliced through trilobites and other prey with a circular, pineapple-slice mouth that looks more like a sci-fi gadget than anything alive today. Anomalocaris was once thought to be several different animals before scientists pieced together its parts, revealing a top predator that kept the Cambrian ocean’s food web in check.

Opabinia: Five Eyes and a Vacuum Hose Nose

Opabinia is the creature that makes you do a double take. With five eyes perched on stalks and a long, flexible proboscis ending in a claw, it looks like it was designed by a committee with a sense of humor. Despite its strange appearance, Opabinia was a successful hunter, using its “hose” to probe the seafloor for prey. Its unique body plan is unlike anything before or since, a testament to the wild experimentation that characterized Cambrian life. When Opabinia was first unveiled, the scientific audience reportedly burst out laughing—proof that nature’s creativity can still surprise the experts.

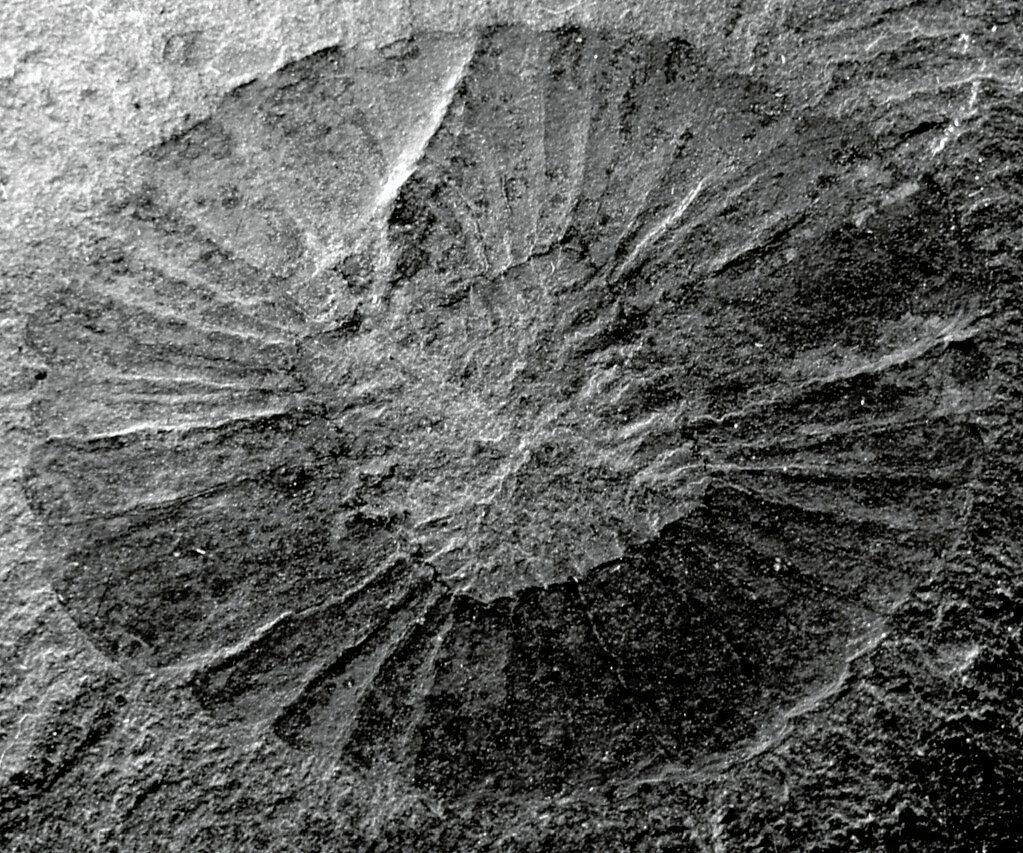

Marrella: The Lace Crab That Wasn’t

Marrella is often called the “lace crab,” although it’s neither a crab nor lace-like upon closer inspection. Instead, it’s a small, delicate arthropod with a shield-like head and long spines trailing behind. It’s the most common fossil in the Burgess Shale, yet it doesn’t fit neatly into any modern group. Marrella shows us that evolutionary “dead ends” can be just as fascinating as today’s success stories. Its intricate body reminds us how even the smallest creatures played a role in shaping ancient ecosystems.

Wiwaxia: The Armored Slug

Wiwaxia looks a bit like a cross between a slug and a medieval weapon—covered in rows of overlapping scales and bristling with long spines. Nobody’s quite sure where it fits in the tree of life, but it was clearly well-defended against predators. Its mouth was ringed with sharp, comb-like teeth, possibly used to scrape algae from rocks. Wiwaxia’s strange mix of features highlights the evolutionary arms race that unfolded during the Cambrian Explosion, with animals inventing new ways to eat, move, and stay alive.

Nectocaris: The Early Cephalopod?

Nectocaris is a small, soft-bodied animal that looks like a cross between a squid and a kite. For years, it was a mystery, with scientists debating whether it was related to arthropods, worms, or something else entirely. Recent research suggests Nectocaris might be an early cousin of today’s squids and octopuses, making it one of the oldest cephalopods on record. Its streamlined body and fin-like appendages hint at the beginnings of jet propulsion, one of the most sophisticated ways to get around in the ocean.

Pikaia: The Unexpected Chordate

Pikaia may look unassuming—a small, fish-like creature with a flattened body—but it holds a special place in the story of evolution. It’s one of the earliest known chordates, the group that eventually gave rise to vertebrates like fish, birds, and even humans. Pikaia swam by flexing its body side to side, much like modern eels. Its discovery in the Burgess Shale was a revelation, showing that the roots of our own ancestry stretch back to these ancient, humble swimmers.

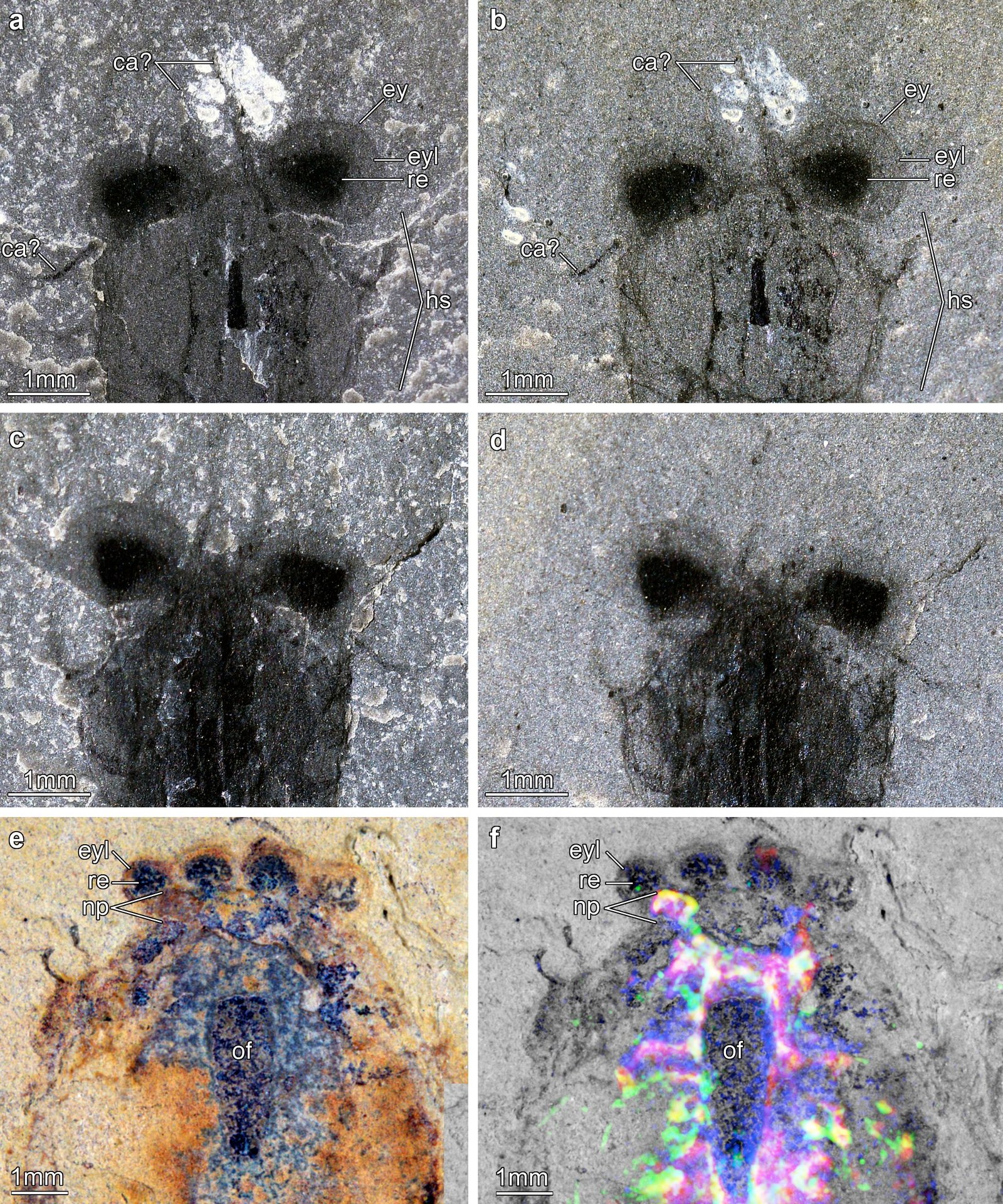

The Miracle of Soft Tissue Fossilization

One of the most astonishing things about the Burgess Shale is how it preserved not just hard shells, but the soft tissues—guts, gills, even eyes—of animals that would normally decay in days. This miracle of fossilization happened because of a unique combination of rapid underwater mudslides and low-oxygen conditions, which quickly buried and protected the creatures from scavengers and bacteria. As a result, scientists can study the fine details of anatomy that are usually lost to time, opening up a new dimension of paleontological research.

The Burgess Shale’s Place in the Fossil Record

The Burgess Shale isn’t the only fossil site from the Cambrian, but it’s by far the most famous, thanks to its exceptional preservation and sheer diversity of life. It captures a unique moment when the rules of evolution were still being written, with animals trying out every possible body plan. Many of the creatures found here have no living descendants, making the Burgess Shale a snapshot of evolutionary experiments—some successful, others destined for extinction. Its importance lies not just in what survived, but in the stories of those that didn’t.

The Rise and Fall of Cambrian Oddballs

Many of the Burgess Shale’s strangest residents—like Hallucigenia and Opabinia—represent evolutionary dead ends. They flourished for a time, then disappeared, leaving no modern relatives behind. This pattern reminds us that evolution isn’t a straight line, but a wild, branching tree full of twists, turns, and pruning. For every lineage that led to today’s animals, countless others vanished, their stories preserved only in rare sites like the Burgess Shale. These lost worlds are a humbling reminder of nature’s unpredictability.

What the Burgess Shale Tells Us About Evolution

The fossils of the Burgess Shale challenge the idea that evolution is always gradual and predictable. Instead, they show that life sometimes leaps forward in bursts of creativity, followed by periods of extinction and consolidation. The mind-boggling variety of forms hints at a time when natural selection was sorting through a chaotic jumble of possibilities. Some innovations stuck, others faded away, but together they shaped the path of life for hundreds of millions of years to come.

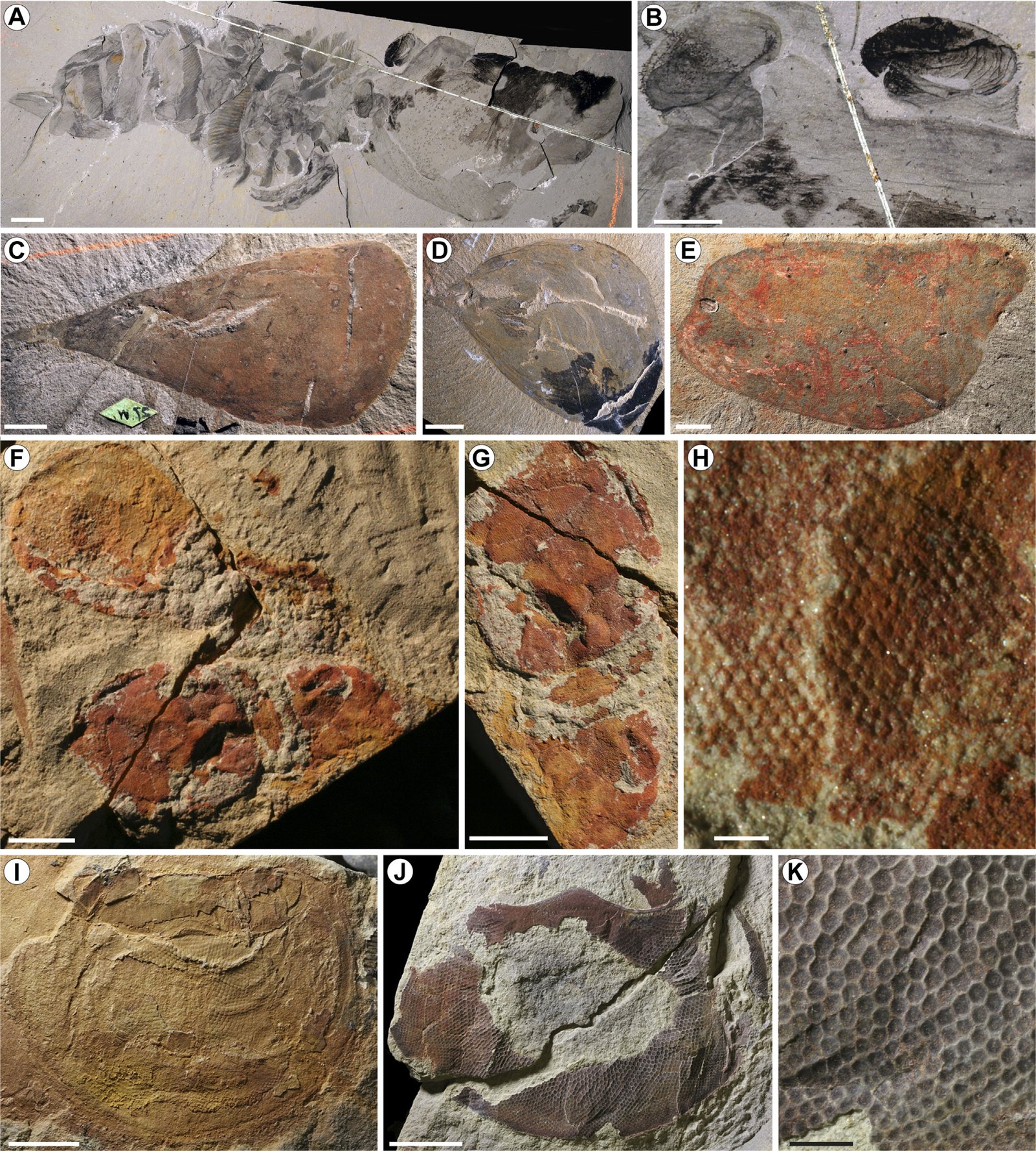

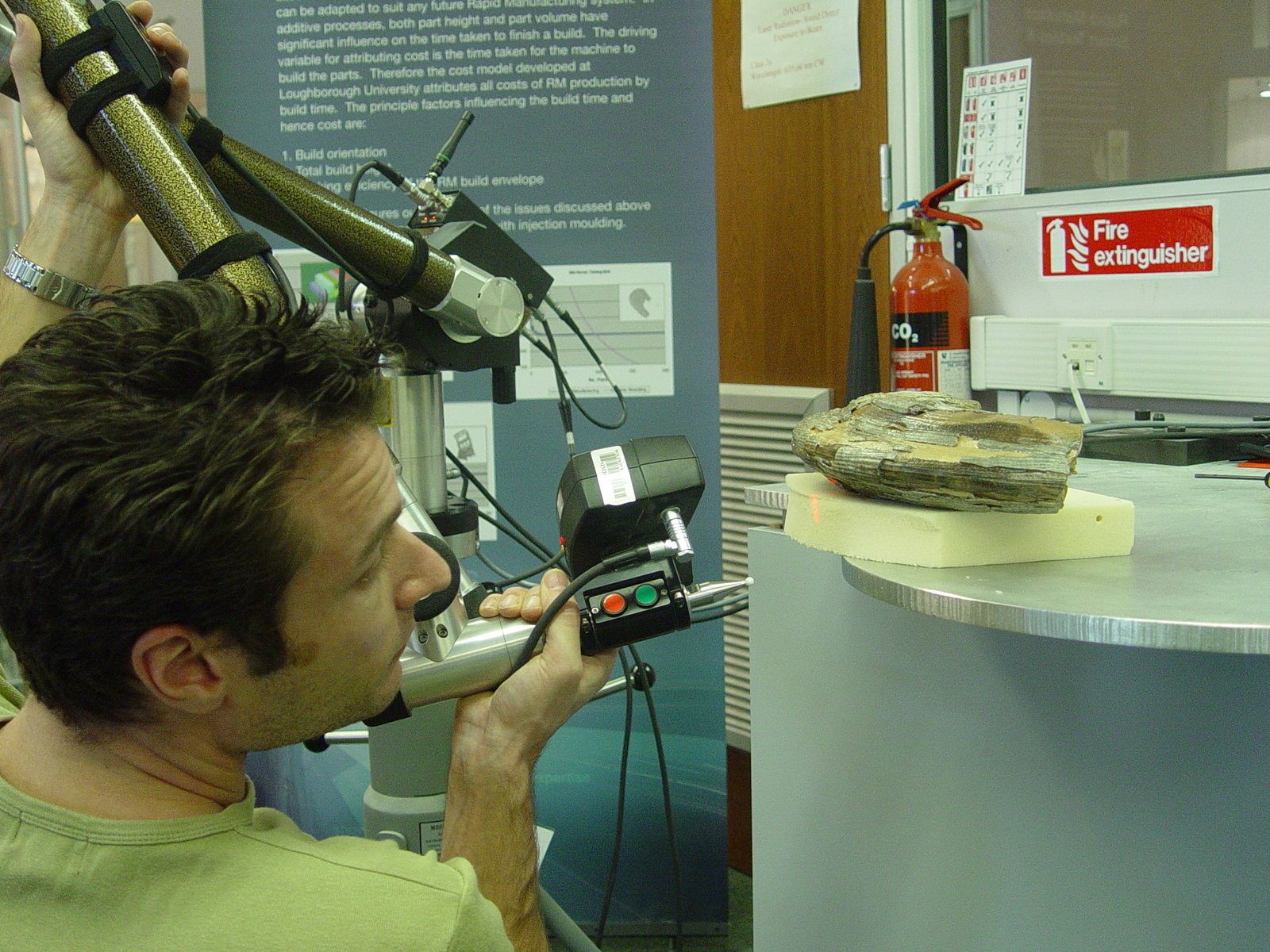

Modern Techniques, New Discoveries

In recent years, scientists have returned to the Burgess Shale armed with high-tech tools—CT scanners, electron microscopes, and computer modeling—to peer inside fossils without destroying them. These methods have revealed even more details about ancient anatomy, such as the structure of eyes, muscles, and even nervous systems. New discoveries continue to emerge, sometimes overturning what we thought we knew and reminding us that science is always a work in progress. The Burgess Shale remains a hotbed of research, sparking heated debates and fresh insights every year.

Global Connections: Other Cambrian Sites

The Burgess Shale isn’t alone in preserving the wonders of the Cambrian Explosion. Similar sites have been found in China (the Chengjiang biota), Australia, and Greenland, each with its own unique menagerie of ancient life. These sites help scientists piece together the global story of early animal evolution, showing how different ecosystems experimented with similar ideas. Comparing these fossil beds deepens our understanding of how life spread and diversified across ancient oceans.

Popular Culture and Public Fascination

The Burgess Shale has captured the imagination of not just scientists, but artists, writers, and the public at large. Its creatures have inspired books, documentaries, and even works of art. Stephen Jay Gould’s book “Wonderful Life” brought the story to a wider audience, emphasizing the role of chance and contingency in evolution. The sheer weirdness of these fossils reminds us that the natural world can be stranger than fiction, fueling a sense of wonder and curiosity that transcends generations.

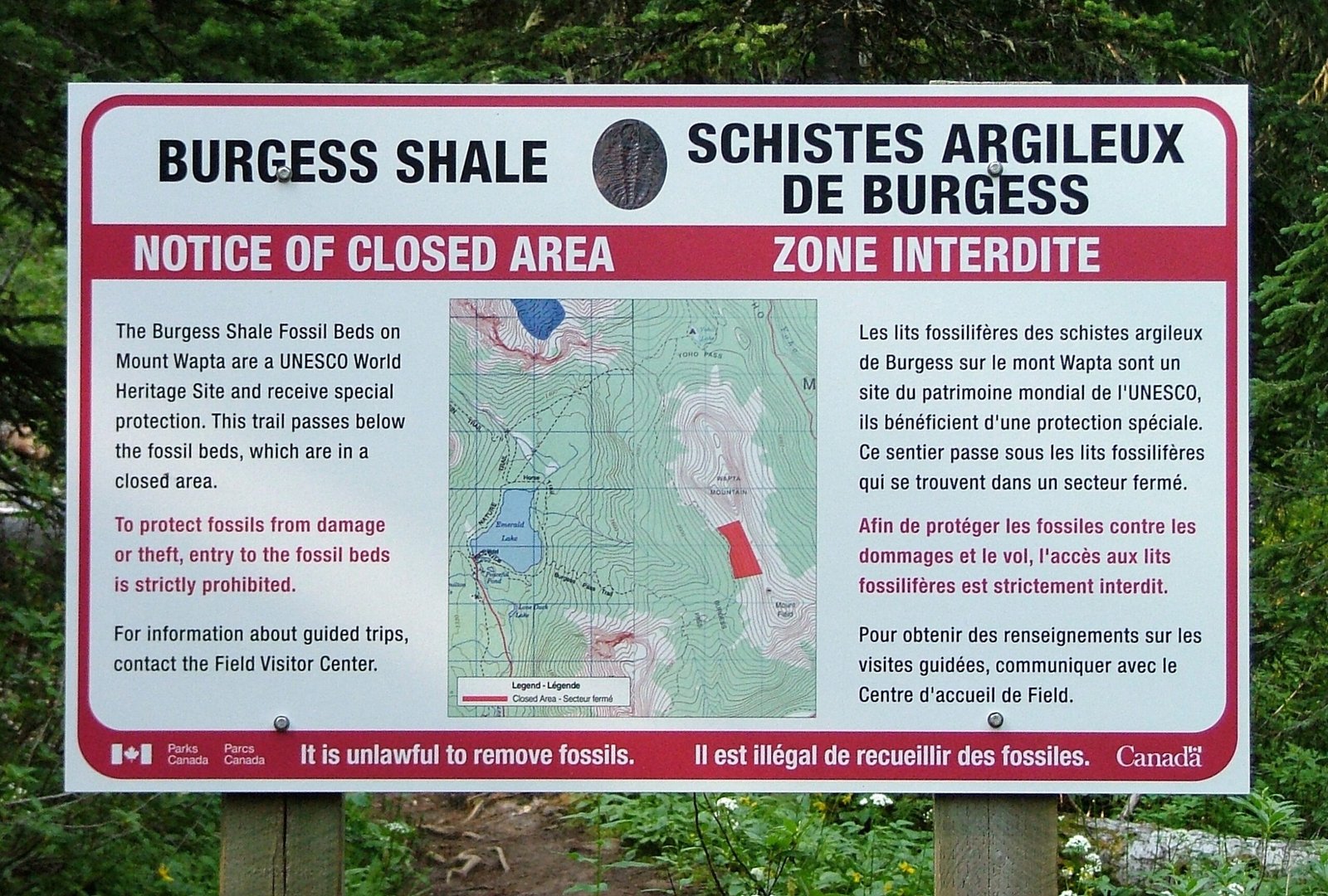

Conservation and Ongoing Protection

The Burgess Shale is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, protected for future generations to study and marvel at. Strict regulations control fossil collecting, ensuring that these priceless records aren’t lost to private collectors or careless digging. Ongoing research is carefully managed to balance scientific discovery with preservation, so that new generations can continue to unlock the secrets buried in these ancient rocks. The site stands as a testament to the importance of safeguarding our natural heritage.

Lessons for Today’s Biodiversity Crisis

The story of the Burgess Shale is more than just a tale of ancient oddities—it’s a powerful reminder of life’s fragility and resilience. The Cambrian Explosion was followed by mass extinctions that wiped out many of its strangest experiments. As we face modern biodiversity crises, the Burgess Shale offers a stark lesson: evolutionary success can be fleeting, and today’s dominant forms may not last forever. Understanding this ancient world helps us appreciate the delicate balance of ecosystems, both past and present.

The Burgess Shale’s Enduring Mystery

Even after more than a century of study, the Burgess Shale continues to baffle and delight scientists. New fossils, new technologies, and new ideas keep changing our picture of the Cambrian world. Each discovery raises fresh questions: Why did some body plans succeed while others vanished? What hidden creatures still wait to be found? The Burgess Shale reminds us that the story of life is far from finished—and that the most amazing chapters may still be waiting to be uncovered.