Have you ever wandered through a botanic garden and felt the hairs on the back of your neck prickle as you passed a patch of curious, almost alien-looking plants? There’s something thrilling—almost dangerous—about carnivorous plants. With leaves that snap shut like a bear trap, sticky tendrils gleaming in the sunlight, and pitchers deep enough to drown a mouse, these botanical predators are the stuff of both nightmares and wonder. The idea that a plant might be waiting to devour your finger is both hilarious and a little bit unsettling. But in reality, these plants are more than just oddities tucked away in glasshouse corners. They’re marvels of evolution, living proof that in nature, the line between predator and prey is never as clear as we think. Let’s take a walk among the hungry green jaws of the world’s most fascinating flora—just keep your hands to yourself.

Venus Flytrap: The Legendary Jaw Snapper

The Venus flytrap is the superstar of carnivorous plants, recognizable by its spiky, toothed “mouths” that snap shut with astonishing speed. Native to the wetlands of the Carolinas, this plant has evolved a mechanism so sensitive that even the lightest trigger—such as an unsuspecting insect—sets off its trap. The plant’s leaves close in less than a second, trapping anything inside. It doesn’t actually want to eat your finger, but the strength of its jaws would certainly startle you if you tried. Scientists are endlessly fascinated by how these traps work, with electrical impulses firing through the plant like nerves in an animal. The flytrap is a living contradiction: it looks delicate, but it’s a ruthless hunter in its own right.

Sundews: The Living Flypaper

Sundews are some of the most beautiful and deadly plants you’ll find in a botanic garden. Their leaves are covered in glistening droplets that look like morning dew, but don’t be fooled—those droplets are sticky, enzyme-rich traps. Insects that land on a sundew get hopelessly stuck. Slowly, the leaf curls around the prey, pulling it in for digestion. There are over 200 species of sundews, each with their own twist on this sticky strategy. Watching a sundew in action is both mesmerizing and a little bit stomach-churning, as if you’re witnessing a miniature horror movie. Their slow, deliberate movements remind you that patience can be the deadliest weapon of all.

Pitcher Plants: Nature’s Pitfall Traps

Pitcher plants look like something out of a fantasy novel, with tall, colorful tubes that beckon insects—and sometimes even small mammals—into their depths. The rim of the pitcher is often slippery, causing victims to tumble inside, where they’re digested by a soup of acids and enzymes. Some species, like the Nepenthes rajah, are large enough to trap rodents. While your finger would likely escape intact, the mere idea is enough to make you shiver. These plants thrive in nutrient-poor soils, making up for what they lack by becoming predators in their own right. Their bold colors and patterns act as irresistible lures, turning the tables on the animal kingdom.

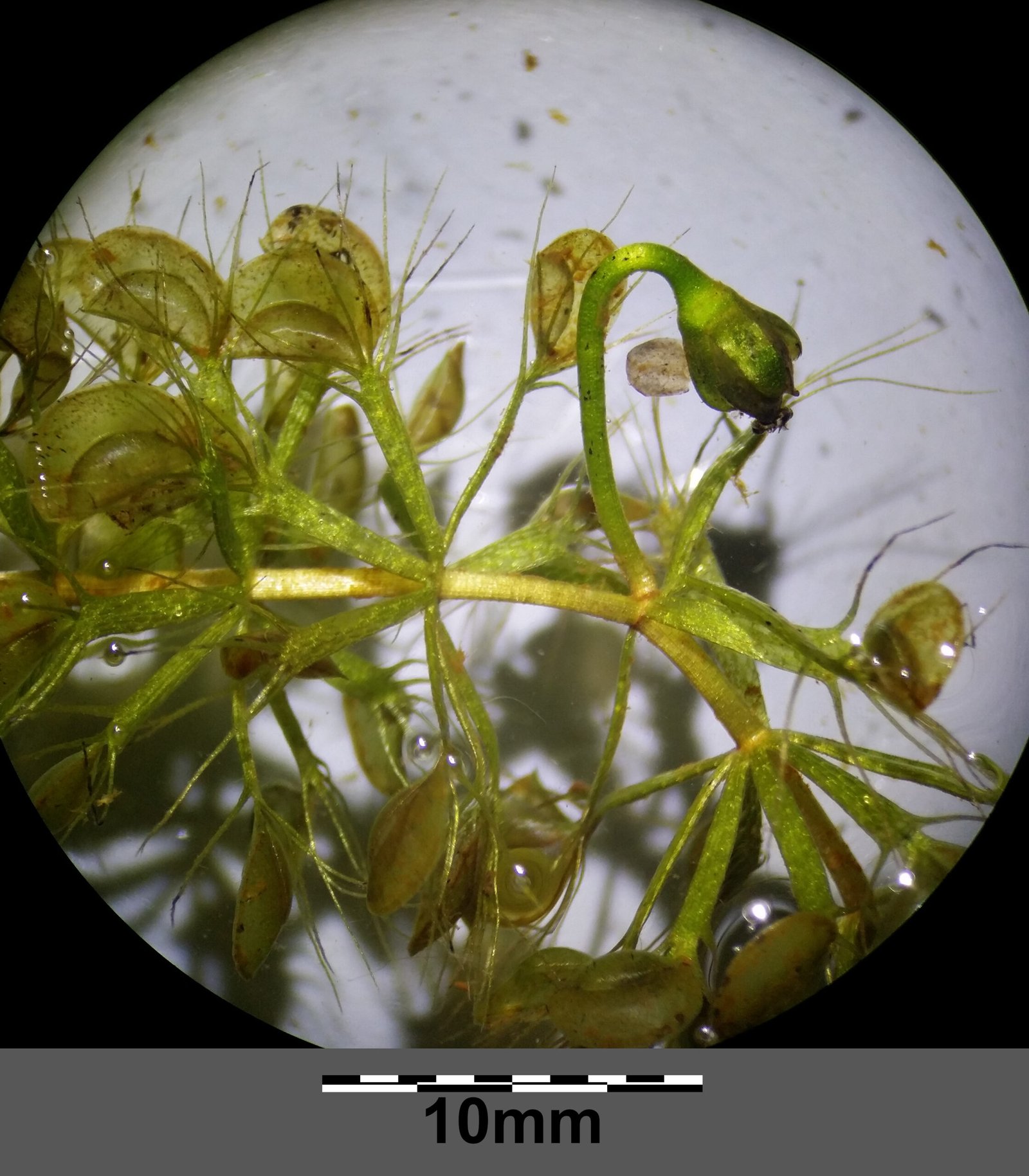

Bladderworts: The Underwater Assassins

Bladderworts are carnivorous plants that hunt beneath the surface of ponds and wetlands. Their tiny, bladder-like traps create a vacuum, sucking in any small creature that dares to swim too close. The trap snaps shut in less than a millisecond, making it one of the fastest movements in the plant world. To the casual observer, bladderworts look harmless, but beneath the water, they’re relentless hunters. They feast on tiny aquatic animals, from water fleas to tadpoles, digesting them within their invisible prisons. The speed and efficiency of these plants are almost supernatural, proving that even the quietest plants can be deadly.

Butterworts: The Slick Hunters

Butterworts might be overlooked because of their simple, unassuming appearance, but their leaves are coated with a greasy, sticky substance that acts like glue. When an insect lands, it quickly finds itself immobilized. The butterwort then secretes digestive juices, breaking down the prey and absorbing the nutrients. These plants are masters of subtlety—there’s no dramatic movement, just a slow, inevitable demise for any insect that gets too close. Butterworts are often used in the fight against household pests, earning them a place in both science and homemaking lore. Their quiet brutality is a reminder that nature’s most effective hunters aren’t always the loudest or flashiest.

Cobra Lilies: The Deceptive Serpents

Cobra lilies are among the most visually striking carnivorous plants, with hoods that resemble the head of a rearing snake. Found in the boggy landscapes of northern California and Oregon, these plants lure insects with their vivid colors and sweet nectar, only to trap them inside their labyrinthine interior. The inside of the hood is lined with transparent windows that disorient prey, making escape nearly impossible. Insects wander in circles, eventually falling into the plant’s digestive chamber. If you ever see a cobra lily in person, you can’t help but feel a mix of awe and fear—nature’s mimicry is as cunning as it is beautiful.

Monkey Cups: The Rainforest Pitchers

Monkey cups, a nickname for tropical Nepenthes, are famed for their large, hanging pitcher traps. These pitchers can be so big that they collect rainwater, and local monkeys have been seen drinking from them—hence the name. But for smaller animals, these pitchers are a death sentence. Insects, frogs, and even small rodents have been found inside these natural traps. The inside walls are slippery, preventing escape, while the bottom is filled with a deadly digestive broth. The monkey cup’s size and strength are a testament to the power of evolution, turning a simple leaf into a lethal pitfall.

Australian Rainbow Plants: The Shimmering Killers

Australian rainbow plants, or Byblis, dazzle with their iridescent leaves covered in sparkling, sticky hairs. Their beauty is deceptive; the glistening droplets are traps for unsuspecting insects. Once an insect is stuck, the plant releases digestive enzymes to break it down, much like a sundew. Rainbow plants thrive in harsh environments where nutrients are scarce, relying on their carnivorous habits to survive. Their shimmering appearance is so captivating that it’s easy to forget they’re deadly, a reminder that nature’s predators often come in the most alluring packages.

Waterwheel Plant: The Rotating Trap

The waterwheel plant is a rare aquatic relative of the Venus flytrap, with underwater snap-traps that close on small aquatic animals. Each spoke of the waterwheel is lined with sensitive hairs, ready to spring into action when touched. This plant is so rare that seeing one in a botanic garden is a real treat. The speed and precision of its traps are almost mechanical, a marvel of natural engineering. The waterwheel plant is a reminder that carnivory isn’t limited to land—it thrives wherever life gets tough and nutrients are hard to come by.

Brocchinia: The Bromeliad with a Taste for Meat

Brocchinia is a genus of South American bromeliads that have evolved to trap and digest insects in their water-filled leaf bases. Unlike other pitcher plants, Brocchinia uses a combination of slippery surfaces and waxy coatings to make it nearly impossible for insects to escape once they fall in. These plants are a fascinating example of convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar strategies to solve the same problems. Their subtle approach to carnivory is a quiet but potent reminder of nature’s ingenuity.

Roridula: The Mutualistic Hunter

Roridula plants from South Africa are sticky insect trappers, but they don’t digest their prey directly. Instead, they form partnerships with predatory bugs that eat the trapped insects and then “fertilize” the plant with their droppings. This peculiar mutualism is a twist on the typical carnivorous plant story. Roridula’s leaves are covered in resinous hairs that trap even the largest of insects, including wasps and bees. The plant’s strategy is a strange but effective way to survive in nutrient-poor soils, showing that sometimes teamwork is the key to survival.

Cephalotus: The Australian Pitcher Plant

Cephalotus follicularis, or the Albany pitcher plant, is a tiny powerhouse from southwestern Australia. Its small, toothy pitchers are perfectly designed to trap insects, with slippery rims and a reservoir of digestive fluids. Unlike other pitcher plants, Cephalotus is compact and unassuming, but it’s no less deadly. The plant’s unique appearance and efficient trapping mechanism have made it a favorite among collectors and scientists alike. Its ability to thrive in challenging conditions is a testament to the power of adaptation.

Heliamphora: The Sun Pitchers of the Tepuis

Heliamphora, or sun pitchers, are native to the misty tabletop mountains of Venezuela and Guyana. These plants form graceful, upright pitchers that collect rainwater and lure insects with nectar. Once inside, escape is nearly impossible due to the slick inner walls and downward-pointing hairs. Heliamphora plants are adapted to some of the harshest environments on Earth, where soil nutrients are scarce and only the most creative survival strategies will do. Their elegant form belies their deadly function, capturing the imagination of anyone who sees them.

Triphyophyllum: The Shape-Shifting Plant

Triphyophyllum peltatum is a rare African plant that only becomes carnivorous at a certain stage in its life cycle. When it needs extra nutrients, it grows long, sticky leaves that trap insects. This shape-shifting ability is unique among carnivorous plants and highlights the flexibility of survival strategies in the plant world. Triphyophyllum’s strange transformation is almost like something out of a science fiction novel, showing that plants can be just as dynamic and surprising as animals.

Drosera Glanduligera: The Catapulting Sundew

Drosera glanduligera, also known as the catapulting sundew, employs a remarkable hunting strategy. Its leaves are lined with snap-tentacles that fling unsuspecting insects onto sticky pads, where they are digested. This rapid-fire action is one of the fastest movements in the plant kingdom, rivaling even the Venus flytrap. The catapulting sundew’s ability to “throw” its prey is both shocking and ingenious, a reminder that evolution is relentless in its creativity. Watching one in action is a true spectacle, as if you’re witnessing a tiny, alien ambush.

Aldrovanda: The Waterwheel’s Cousin

Aldrovanda vesiculosa, commonly called the waterwheel plant, is another aquatic carnivore closely related to the Venus flytrap. Its traps are tiny but terrifyingly efficient, snapping shut on water fleas and mosquito larvae in the blink of an eye. The plant floats freely in ponds and lakes, using its rapid traps to capture prey and supplement its diet. Aldrovanda’s fast movements and underwater lifestyle make it a living paradox: delicate and deadly, graceful yet ruthless.

Genlisea: The Corkscrew Traps

Genlisea species, often called corkscrew plants, live in waterlogged soils and capture tiny organisms using underground traps shaped like twisting tunnels. These traps act as one-way corridors, guiding prey deeper until they can’t escape. Genlisea’s bizarre underground hunting technique is unlike anything else in the plant world. The complexity of these traps, combined with their near-invisibility, makes them a real botanical mystery—proof that the fiercest battles are often fought out of sight.

Darlingtonia Californica: The Serpentine Pitcher

Darlingtonia californica, also known as the California pitcher plant or cobra lily, is famed for its serpentine appearance and cunning trapping mechanism. Its hollow leaves form a twisted maze that confuses insects, while hidden exits and translucent patches make escape nearly impossible. The plant’s roots are unusually sensitive to temperature, requiring cool water to survive. This delicate balance of beauty and danger draws countless visitors to botanic gardens, where the cobra lily stands as a living testament to the wild imagination of evolution.

Pinguicula Gigantea: The Giant of the Butterworts

Pinguicula gigantea is the largest of the butterworts, native to Mexico’s cloud forests. Its broad, sticky leaves trap everything from gnats to moths, making it a formidable predator. Unlike smaller butterworts, P. gigantea can take down larger prey, supplementing its diet with a steady stream of insects. The plant’s size and appetite are a reminder that even the gentlest-looking leaves can hide a ruthless hunger. In botanic gardens, P. gigantea is a crowd favorite, drawing gasps from visitors who realize just how much it can consume.

Why Carnivorous Plants Captivate Our Imagination

Carnivorous plants blur the line between plant and animal, sparking our curiosity and challenging our assumptions about the natural world. Their strange shapes, cunning traps, and dramatic feeding strategies make them irresistible to anyone with a sense of wonder. In botanic gardens, they’re often the stars of the show, drawing crowds who marvel at their beauty and menace. The idea that a plant could “eat your finger” might be exaggerated, but the thrill of encountering these green predators is very real. Carnivorous plants invite us to look closer, to question what we know, and to appreciate the wild creativity of evolution.