Some stories die quietly in dusty libraries; the Anunnaki myth keeps kicking its way back into the spotlight. Born in the clay tablets of ancient Mesopotamia, it now lives on in YouTube documentaries, conspiracy forums, and even arguments about hidden planets in our own solar system. The idea that powerful beings from the sky shaped human destiny refuses to fade, especially when mixed with modern claims about undiscovered worlds like a hypothetical Planet Nine. This article untangles where the Anunnaki actually come from, how they became entangled with space-age speculation, and why this ancient story still grips imaginations in an era of precision telescopes and planetary surveys.

From Clay Tablets to Cosmic Beings

The original Anunnaki were never spacefaring reptilian overlords in flying machines; they were a group of deities in Sumerian, Akkadian, and Babylonian traditions, associated with the heavens, the earth, and the underworld. Their names appear in cuneiform texts going back more than four thousand years, on tablets excavated from sites in what is now Iraq. In these sources, the Anunnaki are often described as a council of gods who witness oaths, sit in judgment, or attend great assemblies of the divine. They are part of a dense, local religious world, not visitors from beyond the orbit of Neptune.

That grounding matters, because the ancient texts we have are surprisingly mundane in tone: they talk about land disputes, offerings, royal rituals, floods, and dynasties far more than they describe anything that looks like science fiction. The Anunnaki belong to the same narrative universe as the storm god Enlil and the hero Gilgamesh, rooted in the social and political anxieties of early city life. When you read translations by professional Assyriologists, the stories feel closer to theology and kingship propaganda than to astronaut lore. The leap from divine council to alien engineers of humanity happens much later, and it tells us more about modern obsessions than about Sumerian belief.

How a 20th-Century Author Rewired an Ancient Pantheon

The modern Anunnaki-as-aliens narrative coalesced in the late twentieth century, largely through the work of writers who claimed that Mesopotamian myths were misunderstood histories. They argued that references to gods and sky beings were garbled records of advanced extraterrestrial visitors, not symbolic or religious language. This reinterpretation framed clay tablets almost like technical manuals, treating terms for heavenly bodies or divine machinery as literal descriptions of spacecraft and orbital mechanics. From there, the Anunnaki were recast as a technologically superior species shaping human genetics and civilization.

The problem is that these readings mostly ignore the linguistic, cultural, and archaeological context that gives ancient texts their meaning. Professional scholars spend careers cross-checking vocabulary, variant myths, scribal errors, and regional variations across thousands of fragments; the alien reinterpretations tend to cherry-pick evocative passages and strip them of nuance. I remember the first time I compared one of these popular books with an academic translation of the same tablet and felt a bit like someone who had finally learned how a magic trick was done: the mystery was replaced not by boredom, but by respect for the real complexity of the original. That doesn’t make the modern stories less entertaining, but it puts them firmly in the realm of creative reinterpretation rather than recovered history.

The Seductive Promise of Hidden Planets and Secret Histories

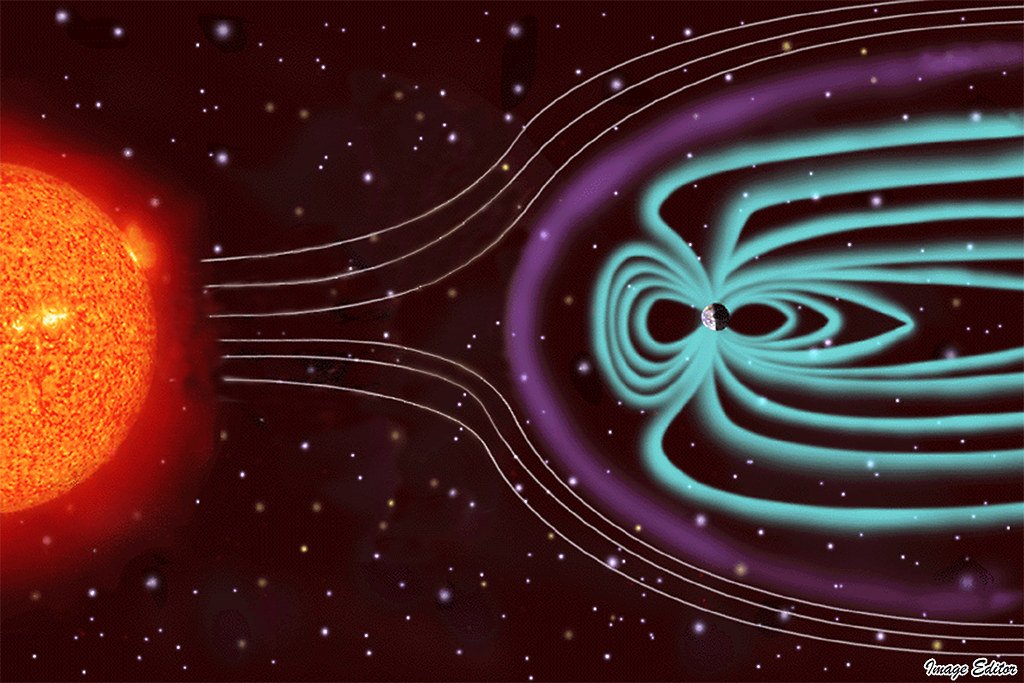

Hidden-planet ideas and the Anunnaki myth feed the same emotional appetite: the sense that there is a larger pattern just out of sight, shaping events behind the curtain. When scientists propose a distant, unseen planet to explain oddities in the orbits of icy bodies beyond Neptune, it can sound uncannily like a modern version of the old gods pulling strings from the sky. Some modern Anunnaki narratives plug directly into this, suggesting that a concealed world, sometimes given a specific orbital period or trajectory, is the true home of these beings. In this vision, astronomy and mythology collapse into one grand revelation.

Yet the scientific search for hypothetical planets in our solar system looks nothing like a treasure hunt for mythic homelands. Planetary scientists use sky surveys, detailed orbital simulations, infrared observations, and painstaking statistics to test whether a hidden planet is really needed to explain what we see. A proposed world has to obey gravity, match observational constraints, and survive scrutiny by skeptical peers who would happily refute a weak claim. What gets lost in the online mash-up of Anunnaki stories and hidden-planet headlines is this basic contrast: myth thrives on narrative power, while science only lets an idea live if it stubbornly fits the data.

What the Actual Mesopotamian Sky Looked Like

Ancient Mesopotamians were careful sky watchers, but their cosmos did not include a rogue, long-period planet visiting from the dark outskirts of the solar system. They tracked the visible planets, the phases of the Moon, and the rising and setting of prominent constellations, mainly for calendrical and omen-reading purposes. Their astronomical records are among the earliest systematic efforts to chart the heavens, but they were tuned to naked-eye phenomena and cyclical patterns that mattered for agriculture and royal decision-making. In that context, the Anunnaki are part of the divine order overseeing these patterns, not inhabitants of a specific, undiscovered world.

When we project twenty-first-century planetary science back onto these records, we risk flattening their richness into a primitive version of our own questions. The scribes who etched star lists onto clay were not trying to build orbital models or hunt for an extra ice giant; they were weaving observations into an interpretive system where eclipses could signal danger and unusual comets might foreshadow political upheaval. That doesn’t mean they were unscientific in spirit – there is real empirical care in how they recorded positions and intervals – but it does mean their aims were fundamentally different. The idea that they quietly encoded the orbital parameters of a hidden, life-bearing planet is not supported by any transparent reading of the texts we have.

Planet Nine and the Temptation to Smuggle in the Anunnaki

The current scientific debate about a hypothetical Planet Nine is a good example of how a real space mystery can be hijacked by older narratives. A few teams of astronomers have argued that the clustering of orbits of some distant icy objects might be best explained by a yet-undetected planet several times more massive than Earth, orbiting far beyond Neptune. This idea is controversial and very much a work in progress; other researchers have suggested that observational bias or the collective gravity of many smaller bodies could create the same patterns. While telescopes search for any sign of this elusive world, the hypothesis lives in a kind of limbo: intriguing, but unproven.

Into that vacuum of certainty, myth-adjacent stories rush in. Online, you can easily find mashups that conflate Planet Nine with a fabled world tied to the Anunnaki, treating the scientific hypothesis as a delayed confirmation of ancient lore. In reality, the numbers driving the Planet Nine idea come from orbital mechanics, not translated myths, and if a new planet is ever confirmed, it will earn its place in textbooks because of how it tugs on other objects, not on human origins. The awkward truth is that the real candidate worlds in our solar system are often stranger and less tidy than myth suggests: frozen, dim, probably lifeless, yet scientifically priceless. The tension between these cold realities and the warm drama of cosmic visitors is part of why the Anunnaki story keeps latching onto every new astronomical whisper.

Why the Anunnaki Refuse to Die: A Cultural Autopsy

At its core, the staying power of the Anunnaki myth reveals less about Sumer and more about us. Humans are deeply uncomfortable with randomness; we want to believe that our species, our technologies, and our crises are part of a deliberate design, even if the designers are indifferent or cruel. Framing the Anunnaki as genetic engineers or planetary landlords offers a strangely comforting narrative: if someone else started this story, maybe they also hold the key to fixing it. That kind of thinking becomes especially seductive during times of rapid technological change and environmental stress, when our own agency feels fragile.

There’s another layer, too: skepticism toward institutions and expertise. When you are already inclined to distrust governments, scientific bodies, or universities, a story that claims they are hiding the true origins of humanity or suppressing knowledge of a visiting planet slides right into that worldview. As a science journalist, I’ve watched that suspicion grow over the last decade, sometimes for understandable reasons, and legends like the Anunnaki become vessels for that unease. They are flexible enough to absorb new fears – genetic engineering, AI, climate change, space mining – and recast them as echoes of an ancient script. The myth endures not because it matches the evidence, but because it is endlessly adaptable to whatever keeps us up at night.

The Deeper Significance: What This Myth Teaches About Science and Story

Peeling apart the Anunnaki narrative from modern planetary science is not just an exercise in debunking; it exposes how differently stories and data operate in our minds. Scientific models are provisional by design, always under attack from new evidence, numerical error checks, and rival interpretations. Myths, by contrast, survive precisely because they can accommodate contradictions and morph with each retelling. When myths collide with science, people often treat them as alternative data sets rather than as different categories of knowledge, and that is where confusion takes root.

Comparing the ancient texts, the twentieth-century alien reinterpretations, and current hidden-planet hypotheses shows a kind of cultural time-lapse. Early Mesopotamian scribes encoded power structures and cosmology; modern fringe writers transformed that material into space-age sagas focused on technology and bloodlines; planetary scientists, meanwhile, chase faint gravitational fingerprints using supercomputers and deep surveys. None of these projects is trivial, but they serve radically different goals. Understanding that distinction is not about stripping wonder from the universe; it is about seeing where wonder actually lives – in difficult measurements, in careful translation, and in stories that are allowed to be myths without being mistaken for orbital diagrams.

Unresolved Questions and the Places Mystery Still Lives

Even after separating myth from evidence, there is no shortage of genuine mystery in our solar system. Astronomers are still debating whether a Planet Nine exists, what carved some of the oddest orbits in the Kuiper Belt, and how many smaller, dark worlds are hiding just beyond the current limits of our surveys. We continue to discover new moons, strange binary objects, and dwarf planets that challenge our tidy definitions of what a planet even is. In that sense, the intuition that there are hidden worlds nearby is absolutely right, even if the details are far stranger and less anthropocentric than Anunnaki stories suggest.

On the human side, researchers are also far from done with the clay tablets themselves. Thousands of fragments in museum collections remain untranslated or only partially studied, and new archaeological work keeps refining our picture of Mesopotamian religion and society. Those real gaps in our knowledge create space where more imaginative narratives can bloom, some responsible, some less so. The task is not to close off that imaginative space, but to keep a clear line between what the evidence can support and what we are spinning because it makes a good story. Mystery is not the enemy of science; it is its fuel, as long as we resist the urge to declare every unknown a confirmation of our favorite legend.

How Curious Readers Can Navigate Between Wonder and Misinformation

If the Anunnaki myth has pulled you in, you are not alone; there is something undeniably compelling about the idea that the stars and our deepest past are entangled. The challenge is to let that curiosity lead you toward better questions instead of quick, satisfying certainties. One simple step is to chase sources backwards: when a claim about ancient aliens or hidden planets grabs you, look for where the original data or text came from, and then compare how different experts interpret it. Even that modest habit starts to reveal the difference between a narrative built on careful work and one that just borrows the language of science.

There are also practical ways to stay engaged without falling into the trap of secret-history thinking. You can follow ongoing surveys for distant solar system objects through observatories that share their results openly, read museum or university translations of Mesopotamian myths, or join public lectures and online courses that unpack how we actually know what we know about early civilizations. None of that has the instant thrill of a hidden planet ruled by ancient beings, but it offers something deeper: the sense of participating, however indirectly, in a long, collective effort to understand our place in a very real cosmos. In the end, maybe the more unsettling and exhilarating thought is not that someone else wrote our story, but that we are still writing it ourselves.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.