Imagine walking through a lush, green forest, sunlight dancing on the scales of a basking lizard. Nearby, a turtle glides through the water and a snake slithers silently in the underbrush. For generations, people have called these creatures “reptiles,” grouping them together in museums, zoos, and textbooks as if they’re one big, scaly family. But what if I told you that the animal kingdom doesn’t actually have reptiles—at least not as a scientifically accurate group? It’s a startling idea, and it challenges everything we thought we knew about these ancient, mysterious creatures. Let’s unravel the scientific story of why the concept of “reptiles” isn’t as clear-cut as you might think.

The Birth of the “Reptile” Category

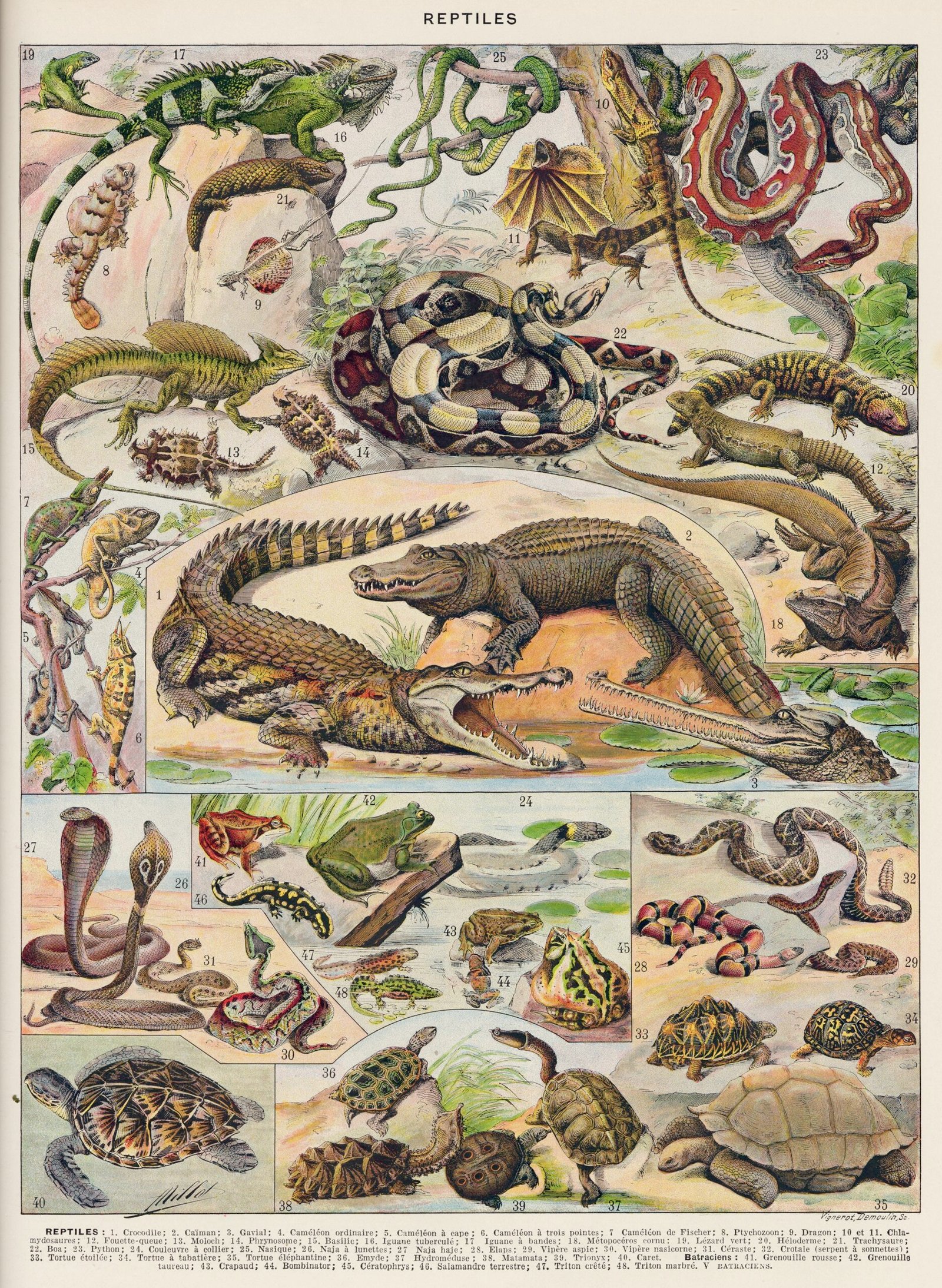

The term “reptile” comes from the Latin word “reptilia,” meaning “to creep,” and for centuries, scientists and naturalists used it to describe scaly, cold-blooded animals that crawled on land. Early biologists grouped snakes, lizards, turtles, and crocodiles together based on their shared physical traits. Back then, classification was all about what creatures looked like, not how they were related. This approach made sense at the time, allowing people to organize and make sense of the natural world. But as science progressed, it became clear that looks can be deceiving, and that nature doesn’t always fit neatly into human-made boxes.

Modern Science and the Tree of Life

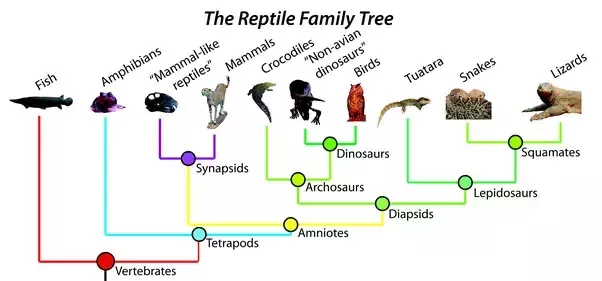

Today, scientists use evolutionary relationships to organize life’s diversity, focusing on ancestry rather than appearance. The “tree of life” concept maps out how all living things are related, branching from common ancestors. When researchers examined reptiles using this method, things got complicated. Birds, for example, are more closely related to crocodiles than crocodiles are to lizards or snakes. This means a group that includes turtles, crocodiles, snakes, and lizards, but not birds, leaves out some of their closest cousins. The idea of “reptile” as a single, natural group crumbles under this scrutiny.

The Problem with Paraphyly

In scientific terms, reptiles are a “paraphyletic” group. That means they include some, but not all, descendants of a common ancestor. Imagine inviting all your cousins to a family reunion except for one branch of the family—that’s what paraphyly looks like. True biological groups, called “clades,” include every descendant from a common ancestor. For reptiles, this would mean including birds, since they evolved from ancient reptilian ancestors. But the traditional definition of reptiles leaves birds out, which makes the category scientifically flawed.

Birds: The Feathered “Reptiles”

It may sound shocking, but birds technically belong within the reptile lineage. Fossil evidence and DNA studies reveal that birds are the direct descendants of a group of two-legged dinosaurs. Their skeletons, eggshells, and even some behaviors are strikingly similar to those of ancient reptiles. When you hear a robin singing in the morning or watch a hawk soaring overhead, you’re witnessing the living legacy of dinosaurs—creatures that, according to evolutionary history, are reptiles in every sense but name.

Turtles: The Outsiders of the Reptile World

Turtles have always puzzled scientists. For years, they were lumped in with reptiles due to their scaly skin and cold-blooded nature. However, genetic studies have revealed that turtles are not as closely related to lizards and snakes as once thought. In fact, their closest relatives may be birds and crocodilians, making the “reptile” label even murkier. This surprising twist shows how appearances can mislead us about evolutionary relationships. Turtles are a perfect example of why the old system doesn’t always tell the whole story.

Crocodilians: The Living Relatives of Dinosaurs

Crocodiles and alligators are often thought of as the ultimate reptiles—ancient, armored, and fierce. But science tells us they have more in common with birds than with most other “reptiles.” Both crocodilians and birds share a unique heart structure and other traits inherited from their dinosaur ancestors. This close connection means that, scientifically, crocodilians belong in the same group as birds. The traditional reptile group, by leaving out birds, fails to reflect this deep evolutionary bond.

Lizards and Snakes: The Squamate Puzzle

Lizards and snakes belong to a group called squamates, which is a true evolutionary clade. They share unique features, like flexible jaws and specialized scales. However, grouping them with turtles and crocodiles under the “reptile” umbrella doesn’t make evolutionary sense. While lizards and snakes are close relatives, their shared ancestry with birds and crocodiles is more distant than you might expect. This makes the classic reptile definition both confusing and outdated in the eyes of modern science.

Amphibians: Not Quite Reptiles, Not Quite Fish

Amphibians—like frogs, salamanders, and newts—are often mistaken for reptiles because of their similar lifestyles and habitats. They’re cold-blooded and often found in the same environments as lizards and snakes. But amphibians split off from the reptile lineage hundreds of millions of years ago. They lay their eggs in water and have soft, permeable skin, setting them apart from the scaly, land-dwelling animals we call reptiles. This distinction helps clarify why grouping animals based on surface similarities can be misleading.

The Rise of Cladistics: A New Way to Organize Life

In the 20th century, a new approach called cladistics revolutionized biology. Cladistics organizes organisms strictly by evolutionary lineage, ensuring that every group—the clades—includes all descendants from a common ancestor. This method exposes the flaws in traditional groupings like “reptiles.” By looking at the deep roots of the tree of life, scientists can group creatures in a way that reflects their true family histories. Cladistics has helped us see that many of our old categories are more about convenience than scientific accuracy.

Why Do We Still Use “Reptile”?

Despite all this scientific upheaval, the word “reptile” is still everywhere. It’s in textbooks, pet stores, and everyday conversations. People love the word because it conjures up a vivid image: tough, scaly survivors from the age of dinosaurs. In education and conservation, “reptile” is a useful catch-all. But when it comes to understanding nature’s real relationships, the term is more of a shortcut than a scientific truth. It’s a reminder of how our language sometimes lags behind our knowledge.

What Does This Mean for How We See Animals?

Realizing that “reptiles” aren’t a true evolutionary group changes how we look at the animal kingdom. It shows us that nature is full of surprises and that our categories are often just tools to help us make sense of complexity. Instead of seeing rigid groups, we start to appreciate the tangled, beautiful web of life that links birds to dinosaurs, turtles to ancient ancestors, and lizards to the distant past. It’s a humbling reminder that science is always evolving, just like the creatures it studies.