Somewhere in a silent forest, an ancient tree is quietly keeping a secret about the Sun. While we go about our lives, its trunk is archiving violent solar storms that blasted Earth centuries or even millennia ago, long before telescopes, satellites, or power grids existed. Every year, as it lays down a narrow new ring of wood, it also stores the fingerprints of invisible cosmic events.

This idea sounds almost mystical at first: that a tree could remember a storm on the surface of the Sun. But it’s not magic; it’s physics, chemistry, and a bit of clever detective work from scientists. By reading the chemistry of tree rings, researchers are now uncovering the history of extreme solar storms – and realizing that the Sun may be far more dangerous, and far less predictable, than we once thought.

The Hidden Diary Inside a Tree Trunk

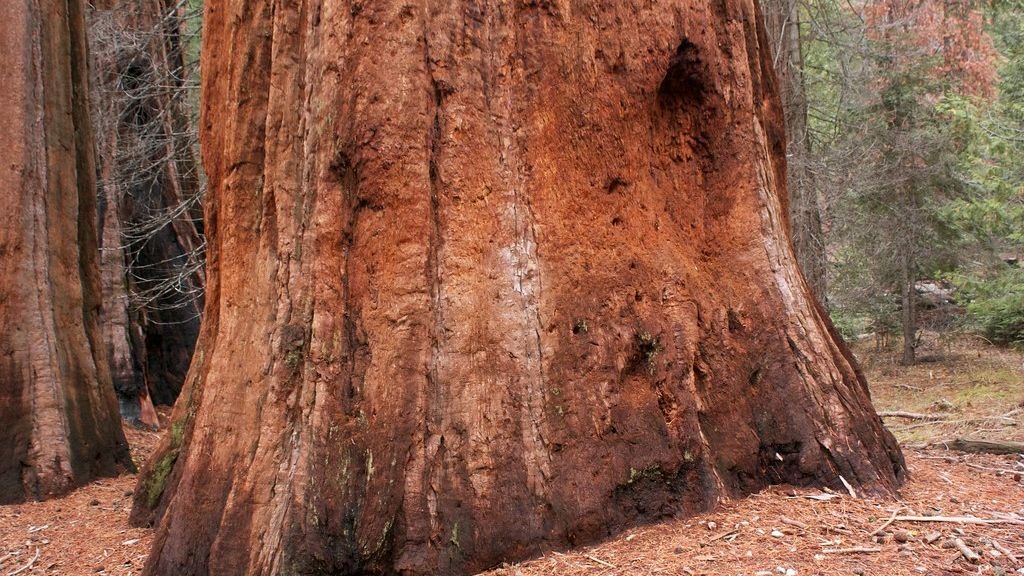

Imagine slicing through a tree trunk and seeing those familiar rings: light, dark, light, dark, spiraling toward the center like an ancient vinyl record. Each ring is one year of the tree’s life, a physical record of the seasons it has endured – wet years, droughts, fires, and even volcanic eruptions. But beneath the visible pattern lies a subtler story written in atoms, not in color.

Inside those rings are tiny amounts of radioactive forms of carbon, especially carbon‑14, created in the atmosphere when high‑energy particles slam into air molecules. Trees absorb carbon from the air as carbon dioxide, so whatever is happening high above – cosmic rays, solar storms, atmospheric changes – gets locked into the wood of that year’s ring. That’s the diary entry: a thin slice of time encoded in chemistry, waiting centuries for someone to read it.

How Solar Storms Leave Their Fingerprints in Wood

When the Sun unleashes a powerful storm, it can hurl high‑energy particles toward Earth in what scientists call a solar proton event. These particles collide with atoms in our upper atmosphere, creating cascades of secondary particles. Some of those collisions turn nitrogen atoms into carbon‑14, a slightly heavier and radioactive version of normal carbon. The more intense the bombardment, the more carbon‑14 gets created in that short window of time.

As that carbon‑14 quickly mixes into the atmosphere and becomes part of carbon dioxide, trees suck it up through photosynthesis and lock it into the ring they’re forming that year. Thousands of years later, researchers can measure the carbon‑14 levels in each ring with extraordinary precision. If they find a sudden, sharp spike in carbon‑14 in a single ring, it’s like a bright red fingerprint saying: something dramatic hit Earth’s atmosphere that year, and the Sun is the prime suspect.

Miyake Events: The Solar Spikes That Shocked Scientists

Over the last decade, scientists have discovered a handful of shockingly large carbon‑14 spikes in tree rings, now known as Miyake events, named after the researcher who first identified one in tree samples from the year 775. These spikes are far bigger than anything seen from ordinary solar activity, and they appear suddenly, within about a year, across trees from multiple continents. That global pattern rules out local causes like nearby volcanic eruptions or regional fires.

Researchers have now found several such events scattered over the last few thousand years, including around the years 775 and 994, and earlier in more ancient wood. These Miyake events seem to mark colossal bursts of high‑energy particles hitting Earth. If they are indeed caused by solar storms, they would make the worst modern solar storms on record – like the famous Carrington Event of 1859 – look relatively small. That realization has forced scientists to rethink how extreme the Sun’s outbursts can actually be.

From Tree Rings to Time Machines: Dating Ancient Solar Storms

What makes tree rings so powerful is not just that they store evidence, but that they store it with a precise date. Dendrochronology, the science of tree‑ring dating, can match patterns of wide and narrow rings across many trees to create continuous timelines that stretch back thousands of years. It works like overlapping puzzle pieces: older dead wood overlaps with younger living trees, building an unbroken calendar of rings year by year.

Once a carbon‑14 spike is found in that timeline, scientists can pin it down to a specific year and sometimes even narrow it to a season. That turns each Miyake event into a timestamp that can also be used to date other materials, like ancient timbers in buildings, shipwrecks, or archaeological sites. It’s as if a solar storm left a glowing mark on the entire planet’s biological clock, one that can sync human history with solar history in a way we never had before.

Why Extreme Solar Storms Are a Modern Problem

For the trees that quietly recorded them, ancient solar storms were dramatic but survivable events. For us, living in a world laced with satellites, GPS, long‑distance power lines, and instant communication, similar storms could be devastating. A truly extreme solar particle event could knock out parts of the power grid, confuse or destroy satellites, disrupt radio communications, and interfere with navigation systems that airlines, ships, and emergency services rely on.

Studies inspired by tree‑ring evidence suggest that such extreme events are not once‑in‑a‑universe flukes; they have happened multiple times in the last few thousand years. That means they are part of the Sun’s normal behavior, even if they are rare. If one occurred today, the economic damage alone could reach into the trillions of dollars, and recovery could take months or longer in some regions. The trees are effectively warning us that the question is not whether the Sun can do this, but whether we are prepared for when it does.

Reading the Trees: How Scientists Decode Solar History

To turn a tree trunk into a solar history book, researchers start by collecting wood from many different places: old growth forests, ancient beams in temples or churches, preserved logs in lakes, even subfossil trees buried in bogs. They slice the wood into thin samples, identify each annual ring, and then carefully separate them. Each ring is then analyzed in the lab to measure the ratio of carbon‑14 to normal carbon, using highly sensitive instruments that can detect tiny differences.

Patterns in those measurements are compared across trees from different regions and then matched with existing carbon‑14 archives. If a sharp, simultaneous spike appears in many trees around the world for the same year, that’s a strong sign of a global event. To strengthen the case, scientists also look at other archives, like ice cores from Greenland or Antarctica, which can record related chemical changes from atmospheric reactions. Step by step, this cross‑checking helps confirm that the trees really are responding to something big happening in space, not just local weather or random noise.

What Ancient Trees Might Tell Us About Our Future

One of the most unsettling lessons from tree‑ring records is that extreme solar events do not line up neatly with the familiar eleven‑year solar cycle. Some Miyake‑like spikes appear during relatively quiet periods, suggesting that the Sun can deliver dangerous surprises even when it seems calm. That unpredictability makes planning for space weather risk more complicated than simply watching for sunspot peaks. It also means we may need to think of extreme solar storms more like we think of massive earthquakes: rare, but inevitable over long time scales.

On the other hand, these same records give us a longer baseline to understand how often such events may occur, and how strong they can get. That information can guide how we design power grids, harden satellites, and build early‑warning systems. Personally, there’s something strangely reassuring in the idea that trees were watching the sky long before we were, quietly recording past storms that we can now study. They can’t tell us exactly when the next major event will hit, but they do remind us that it has all happened before, and it will happen again.

Listening to the Forest to Understand the Sun

Ancient trees do more than mark the passing of years; they connect the soil beneath our feet to violent outbursts on the surface of the Sun. Their rings hold the chemical echoes of solar storms that predate written history, giving us a rare, year‑by‑year record of cosmic events that no human could have witnessed. As we learn to read those subtle clues, we’re forced to update our picture of the Sun from a mostly gentle life‑giver to a sometimes volatile neighbor.

In a way, forests have been quietly taking notes on the universe for millennia, while we were only dimly aware of what was happening overhead. Now, in an age when a single solar storm could ripple through every corner of our technology‑dependent world, those old notes suddenly matter a lot. The next time you walk past a centuries‑old tree, it might be worth wondering: what storms has it already seen, and what might it be recording about our sky right now?