There are moments in history when stone and bronze tumble to the ground, and the world seems to pause, holding its breath. The removal of Confederate monuments across the United States has become one of those electrifying moments—a dramatic, sometimes chaotic spectacle that is about so much more than metal and marble. These statues, once looming over city squares and courthouse lawns, carried the weight of memory, power, and pain. When they fall, they force us to confront uncomfortable questions: Who are we? What do we value? And why does the story told in bronze matter so much to so many? This is more than a debate over history; it’s a living, breathing struggle over identity, belonging, and the scars that shape a nation.

Symbols of Stone: Why Monuments Matter

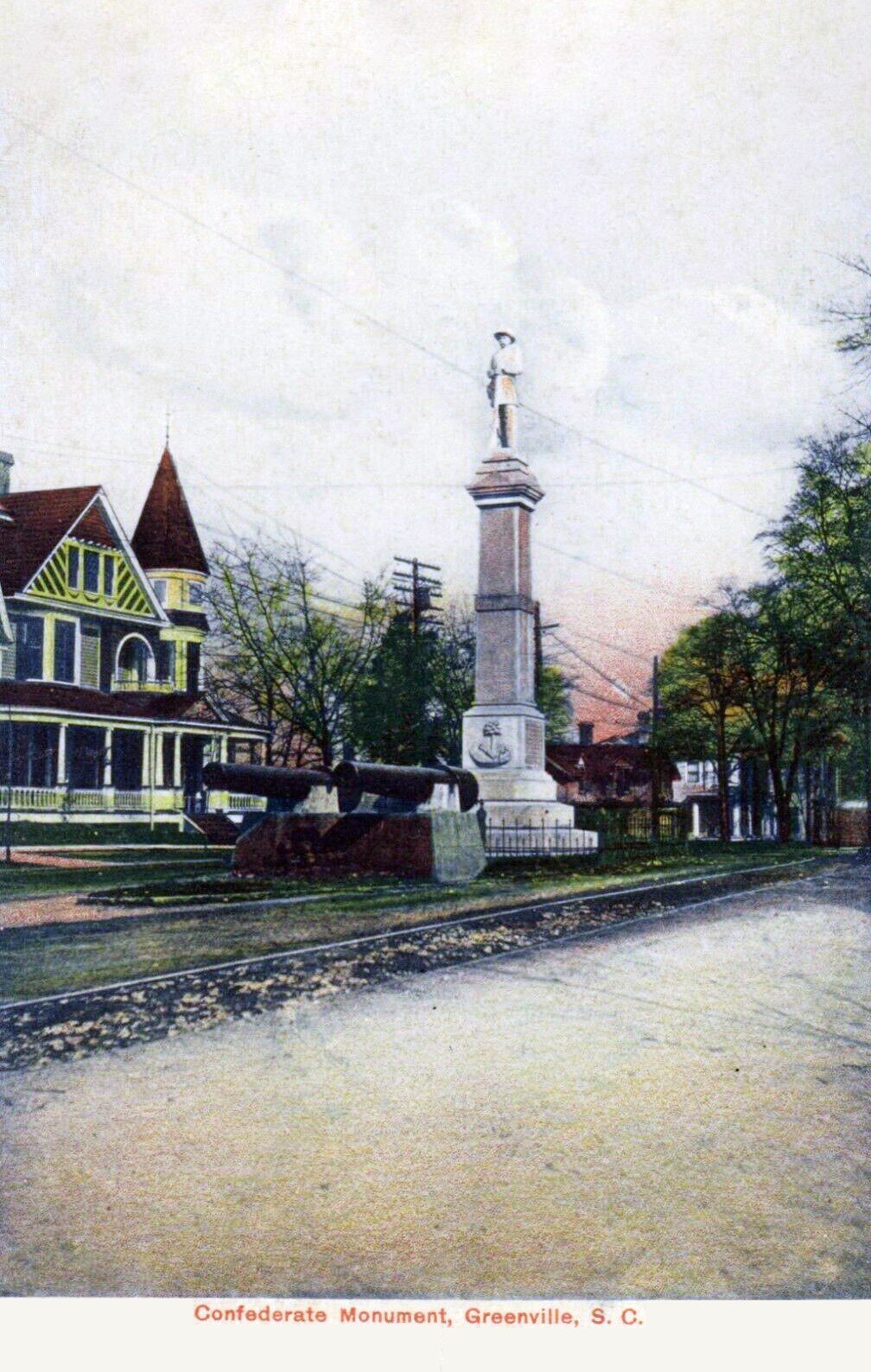

Monuments are not just decorations; they are carefully chosen symbols that speak louder than words. When communities decide who to honor with a statue, they are making a statement about what they believe is worthy of remembrance. Confederate monuments were often erected decades after the Civil War, during times of racial tension, and they sent a clear signal about power and who belonged. These statues shaped how people saw their towns and themselves, quietly influencing public memory. Their presence carried a message that was felt every day by those who walked past them. To many, these monuments were reminders of a painful history that never really went away. The debate about their removal shows how deeply symbols can cut, dividing or uniting people in ways that can be surprising and profound.

The Science of Memory: How We Remember History

Psychologists have long studied how societies create collective memory, and monuments play a crucial role in this process. Memories are not just stored in our minds—they are built into our environments, encoded in the landmarks we walk by every day. The presence of Confederate statues in public spaces subtly shapes our understanding of history, influencing what is celebrated and what is hidden. Studies show that repeated exposure to certain symbols can reinforce specific narratives, making them seem more legitimate or natural over time. When these monuments are removed, it disrupts the familiar landscape, prompting people to question the stories they’ve always been told. The brain’s tendency to hold on to visual cues means that replacing or removing statues can have a surprisingly powerful effect on how communities remember their past.

The Timing of a Tumble: Why Now?

The recent wave of monument removals did not happen by accident—they were sparked by nationwide protests, viral videos, and a growing demand for racial justice. Social movements have a way of accelerating change, and the energy of the past few years has pushed long-simmering debates into the spotlight. As people gathered in city streets, the statues became lightning rods, their very presence provoking outrage and calls for action. The science of social change tells us that visible symbols often become targets when people seek tangible proof of progress. The timing is not just about the past, but about the urgent need to redefine the present. This urgency can be felt in the chants, the murals that replace the statues, and the collective sense that something irreversible is happening.

Community Divides: The Emotional Fallout

The decision to remove a statue is rarely unanimous—communities often find themselves torn, sometimes painfully so. For some, these monuments represent family heritage or local history, creating a sense of pride and continuity. For others, they are daily reminders of oppression and injustice. The emotional reaction to a statue’s removal can be intense, with anger, relief, grief, and hope all colliding in public debates. Neuroscience shows that our brains are wired to respond strongly to threats against our identity, which is why arguments over monuments can feel so personal. The removal of a statue can trigger a flood of emotions, forcing people to confront their own beliefs and the stories they have inherited. These moments can fracture communities, but they can also open doors for healing and new conversations.

The Power of Place: Changing Landscapes

Physical spaces shape how we experience the world, and monuments are a key part of that landscape. When a Confederate statue is taken down, the empty pedestal can feel like a wound—or a blank canvas. Urban planners and psychologists agree that the design of public spaces has a direct impact on community well-being. The removal of monuments changes the way people use and think about those spaces, sometimes creating a sense of liberation and possibility. Some cities have chosen to fill the void with art, gardens, or memorials to different chapters of history. These changes can be disorienting, but they also offer a chance to re-imagine what shared spaces can be. The science of place attachment shows that people are deeply influenced by their surroundings, which is why altering a monument can spark so much emotion and controversy.

History in Flux: The Battle Over Narrative

History is not a fixed story—it’s an ongoing argument about what matters. Removing a statue is not about erasing the past, but about challenging which version of the past gets the loudest voice. Historians point out that Confederate monuments were often part of a deliberate effort to rewrite Civil War history, centering on “Lost Cause” narratives that downplayed slavery and glorified Confederate leaders. By taking down these statues, communities are rejecting one story and opening the door to others. This process can feel unsettling, as if the ground beneath our feet is shifting. But it is also an opportunity for a more honest reckoning with the past, one that makes space for voices that were previously silenced.

The Ripple Effect: Monuments Beyond the South

While Confederate monuments are most common in the American South, the debate has spread far beyond those borders. Statues of controversial figures have come under scrutiny across the country and even around the world. The science of social contagion explains how ideas and movements can spread rapidly, especially in the age of social media. One city’s decision to remove a statue can inspire others to follow suit, creating a domino effect. This ripple effect is a sign that the struggle over public memory is not confined to any one region. The global conversation about monuments reveals how interconnected our stories really are, and how symbols of the past can shape the future in surprising ways.

Art, Identity, and Healing: What Comes Next?

When a statue falls, the question quickly becomes: What should take its place? Some communities have chosen to commission new art that reflects their values, while others have left the pedestals empty as a statement. The process of deciding what to do next can be an opportunity for healing and creativity. Art therapists and psychologists note that creating new symbols can help people process trauma and imagine a better future. The act of building something new together can foster a sense of unity and purpose. The choices communities make in the aftermath of removal reveal their hopes, fears, and visions for what they want to become. These decisions are rarely easy, but they are a powerful testament to the human need for meaning and connection.

The Science of Change: How Societies Adapt

Change is hard, especially when it touches on identity and tradition. Social scientists have found that people are more likely to accept change when they feel involved in the process and when there is space for open dialogue. The removal of Confederate monuments has sparked difficult conversations, but it has also created opportunities for growth and understanding. Societies that are able to adapt to new realities tend to be more resilient in the face of future challenges. The science of adaptation shows that letting go of outdated symbols can make room for new stories and stronger communities. The journey is often uncomfortable, but it is also a sign of progress.

Lessons in Stone: What We Learn About Ourselves

The saga of the fallen statues is, at its core, a mirror held up to society. It reveals our values, our wounds, and our capacity for change. The monuments that once seemed permanent now remind us that nothing in history is truly set in stone. Every community that wrestles with these questions is engaged in a profound act of self-examination. The choices we make about which stories to honor—and which to retire—reflect our deepest beliefs about justice, memory, and hope. The removal of Confederate monuments is not just about the past; it is a living experiment in what kind of future we are willing to build together.