When most stars die, they go out with a bang — exploding in brilliant supernovae that scatter heavy elements across space and light up the cosmos. But astronomers have identified a less violent end for certain stars, where they instead fizz out in complex, filament-laden outflows powered by dense winds. These “failed explosions” offer scientists a new window into stellar death and the diverse ways stars can die without the textbook blast.

Using advanced simulations and observations of unusual remnants like Pa 30, researchers are now linking these unique stellar deaths to broader cosmic processes — from exotic eruption patterns to parallels with terrestrial blast physics. What appears chaotic at first may instead follow hidden patterns, blurring lines between familiar supernova behavior and subtler astrophysical phenomena.

A Strange Stellar Endgame

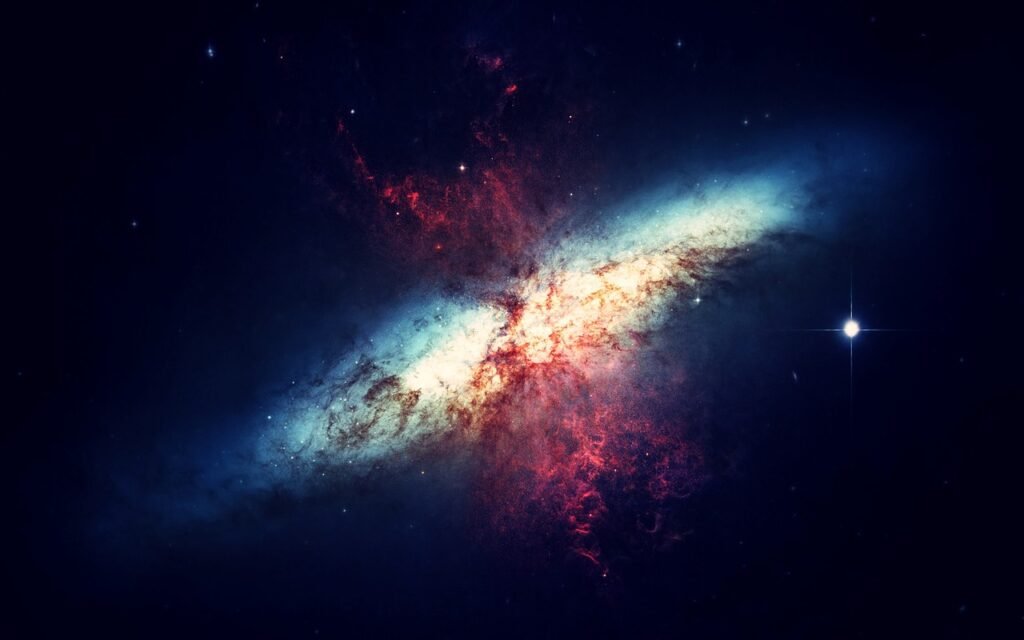

Astronomers have studied a class of stars that do not produce typical supernova remnants. Instead of an explosion that disperses material swiftly in all directions, these stars emit powerful, dense winds that expand gradually, creating elaborate filamentary structures in space.

The object Pa 30 is a leading example: its wind-fed filaments stretch outward without breaking apart into the chaotic patterns expected in ordinary stellar deaths. This process, driven by high wind density, points to a subclass of stellar endings now known as Type Iax phenomena — events that fail to explode conventionally.

Failed Explosions and Filamentary Beauty

What makes these events scientifically intriguing is not just the absence of a classic supernova burst, but the emergence of elegant filamentary structures that continue to grow rather than devolve into chaos. Advanced computational models replicate these patterns, showing that high density contrasts can sustain filament formation over long periods.

Remarkably, simulations draw unexpected parallels between these cosmic filaments and early formation patterns in historical human explosions — such as the 1962 Kingfish nuclear test — where initial filamentary stages precede later stages of turbulence. In the celestial case, the dense wind feeding keeps the structure coherent rather than chaotic.

What These Stars Teach Us

Unusual stellar deaths like those driving Pa 30’s structure remind scientists that the life cycles of stars — even near their ends — are more varied than textbooks suggest. Traditional supernova models may capture many cases, but Type Iax remnants reveal paths where winds dominate over blasts, reshaping how energy and matter are returned to the galaxy.

Understanding this variation is crucial for astrophysics because different end states influence galactic chemistry, the distribution of elements, and the triggers for subsequent star formation. These “soft deaths” might be more common than previously recognized, and their signatures could be hiding in plain sight across the sky.

Beyond Supernovae: Broader Cosmic Context

While Pa 30 represents a specific case, star research continues to expand across a wide range of stellar phenomena. Other studies probe whether exoplanets could have satellites, as in the TRAPPIST-1 system’s case, where moons might exist around Earth-like planets 40 light-years away.

Meanwhile, scientists use hypervelocity stars — ones flung across the Milky Way at extreme speeds — as tools to map our galaxy’s dark matter distribution, providing context for how stellar behavior ties into the vast unseen structures that shape the universe.

New Tools, Fresh Perspectives

Advances in telescopes and computational modeling are allowing astronomers to explore stellar phenomena once thought too exotic or rare to quantify. Observations from large survey telescopes and improved simulations are transforming how we understand the delicate balance between a star’s initial mass, life path, and eventual demise.

This broader view enriches our knowledge of star clusters, galactic evolution, and the interactions between stars and their environments. The data from unusual remnants — including those that don’t explode — are becoming key pieces in a larger cosmic puzzle.

Conclusion: Rethinking Stellar Death in the Cosmos

The discovery that some stars end their lives not with classic supernova explosions but through gentle, wind-driven fading has profound implications. It compels astrophysicists to rethink core assumptions about how stars die and how their remnants contribute to the cosmic ecosystem.

Rather than diminishing in significance, these “failed” stellar deaths enrich our view of the universe as a place full of diversity and nuance. They remind us that cosmic phenomena often escape simple categorization, and that understanding the full life cycle of stars — from birth to unusual death — demands both technological innovation and open-minded inquiry. As we continue to discover these subtler stellar signatures, our picture of the universe becomes more intricate, beautiful and humbling.