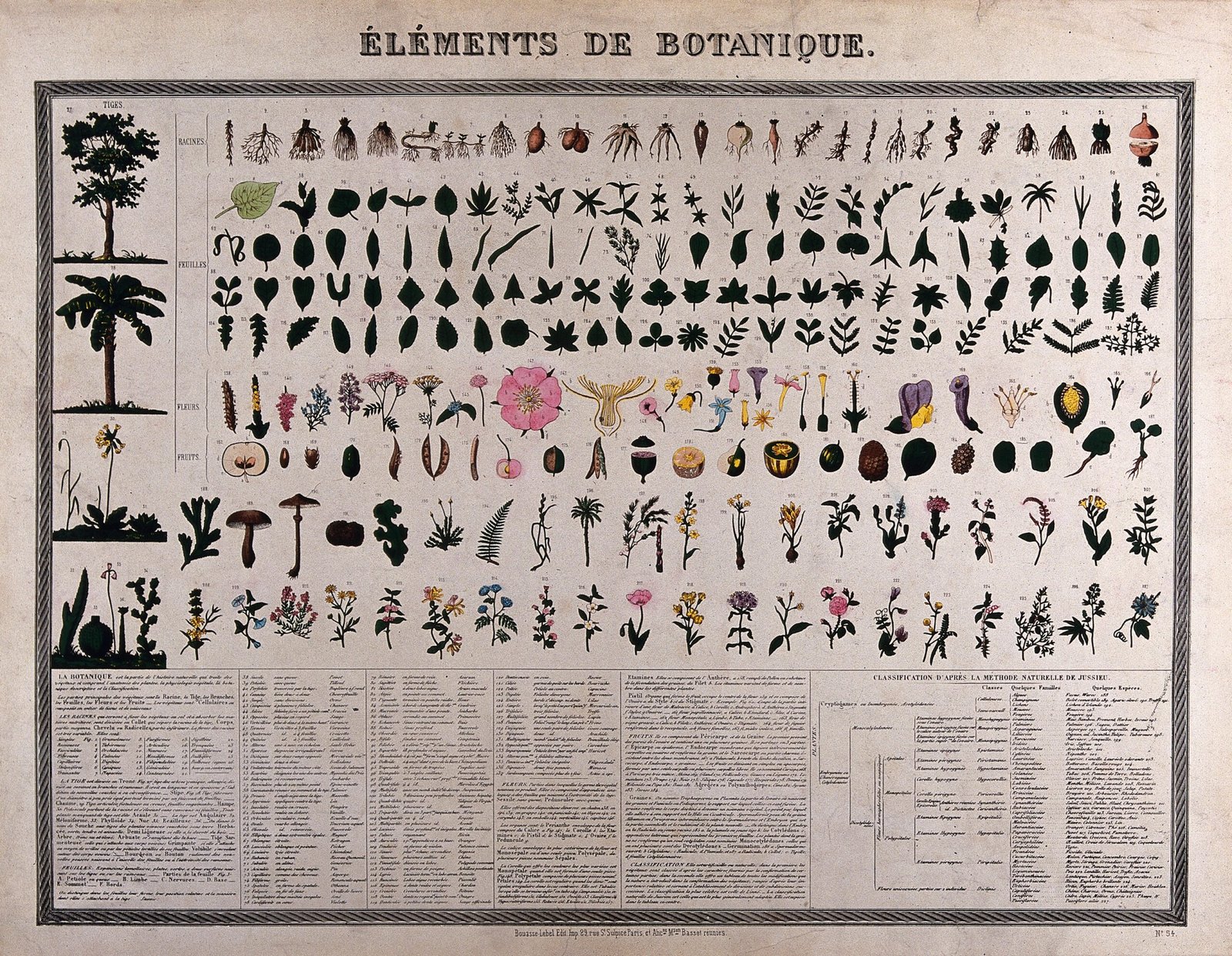

Wait, what? If someone told you that the yellow fruit you slice into your cereal every morning is technically a berry, while those red, heart-shaped strawberries you love aren’t berries at all, you’d probably think they’d lost their mind. But here’s the thing — botany has its own rules, and they’re completely different from what we learned in kindergarten. The scientific world of plant classification is full of surprises that would make your head spin, and fruit categories are no exception.

The Botanical Definition That Changes Everything

In botanical terms, a berry is defined as a fleshy fruit produced from a single flower with one ovary, where the ovary wall ripens into an edible layer. This definition sounds simple enough, but it completely flips our everyday understanding of fruits on its head. The key factor here is that true berries develop from one flower with a superior ovary, and the seeds are embedded directly in the flesh. This scientific classification has nothing to do with size, color, or even taste — it’s all about the plant’s reproductive structure. When botanists look at a fruit, they’re examining how it formed and developed, not whether it tastes sweet or looks like what we’d expect a “berry” to be.

Why Bananas Qualify as True Berries

Bananas check every single box for being a botanical berry, which is honestly mind-blowing when you think about it. They develop from a single flower with one ovary, the ovary wall becomes the fleshy part we eat, and those tiny black specks you sometimes see are actually the seeds (though they’re underdeveloped in the bananas we buy). The banana flower produces this fruit through a process that perfectly matches the scientific definition of a berry. What makes this even more interesting is that wild bananas actually have large, hard seeds that make them nearly inedible — the seedless bananas we enjoy are the result of careful cultivation and selective breeding over thousands of years.

The Strawberry Deception

Strawberries are impostors in the berry world, and the evidence is written all over their surface — literally. Those tiny yellow dots covering a strawberry’s red exterior aren’t just decorative; they’re actually individual fruits called achenes, each containing a single seed. The red, juicy part we eat is technically called a “receptacle,” which is essentially the stem tissue that swelled up to support all those tiny fruits. Strawberries develop from a single flower, but that flower has multiple ovaries, which automatically disqualifies them from true berry status. Instead, strawberries belong to a category called “aggregate accessory fruits,” which sounds way less appealing than just calling them berries.

Grapes: The Obvious Berry Champions

Unlike the shocking banana revelation, grapes being true berries actually makes perfect sense once you understand the definition. Each grape develops from a single flower with one ovary, the skin and flesh come from the ovary wall, and the seeds sit right there in the center where you’d expect them. Grapes are like the poster children for what berries should look like according to botanical standards. Wine lovers have been enjoying true berries all along, though they probably never thought about the botanical classification while sipping their favorite vintage. The fact that grapes come in clusters doesn’t change their individual berry status — each grape is its own separate berry fruit.

Blueberries: Finally, Something That Makes Sense

Blueberries are one of the few fruits where common sense and botanical science actually agree — they really are berries! Each blueberry forms from a single flower with one ovary, and those seeds you sometimes crunch on are embedded right in the flesh where they belong. The crown-like structure at the bottom of each blueberry (the part opposite the stem) is actually the remnant of the flower’s sepals, which is a dead giveaway of its berry credentials. Cranberries, lingonberries, and huckleberries all follow this same pattern, making them part of the exclusive club of fruits that are both commonly called berries and scientifically classified as berries. It’s refreshing to find some consistency in the confusing world of fruit classification.

The Raspberry and Blackberry Betrayal

Prepare yourself for another botanical bombshell: raspberries and blackberries aren’t actually berries at all. These fruits are what scientists call “aggregate fruits,” meaning they’re made up of many tiny individual fruits clustered together. If you look closely at a raspberry or blackberry, you can see all the little round sections that make up the whole fruit — each of those sections is technically its own tiny fruit with its own seed. The entire structure develops from a single flower, but that flower has multiple pistils (female reproductive parts), which creates this cluster effect. When you eat a raspberry or blackberry, you’re actually eating dozens of tiny fruits all smooshed together, which is kind of amazing when you think about it.

Tomatoes: The Vegetable That’s Actually a Berry

The tomato confusion goes way beyond the famous “is it a fruit or vegetable” debate — tomatoes are actually berries, and pretty textbook ones at that. They develop from a single flower with one ovary, the fleshy part comes from the ovary wall, and the seeds are scattered throughout the gel-like interior chambers. From a botanical standpoint, tomatoes are as much berries as grapes or blueberries, regardless of how we use them in cooking. This classification becomes even more interesting when you consider that eggplants and peppers are also berries for the exact same reasons. The next time someone argues about whether tomatoes belong in fruit salad, you can blow their mind by telling them it’s actually a berry salad.

Cucumbers and Their Surprising Berry Status

Here’s something that’ll make you do a double-take at the grocery store: cucumbers are technically berries too. They meet all the botanical requirements — single flower, one ovary, fleshy ovary wall, and seeds embedded in the flesh. The same goes for all members of the cucumber family, including melons, zucchini, and even pumpkins. Yes, you read that right — pumpkins are technically berries, which makes jack-o’-lanterns carved berry displays. This classification shows just how far botanical definitions can stretch from our everyday understanding of what different fruits should be. The science doesn’t care if you put cucumbers in salad instead of your morning yogurt.

The Citrus Berry Connection

Oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits all qualify as berries, though they get their own special subcategory called “hesperidia.” These citrus fruits develop from a single flower with one ovary, but their structure is unique enough to earn special recognition in the botanical world. The thick, oily peel and the segmented interior filled with juice vesicles make them different from other berries, but they still meet the basic requirements. Each segment of an orange contains seeds (or would, if we hadn’t bred most of them to be seedless), and the whole fruit develops from that single ovary. So technically, when you’re drinking orange juice, you’re drinking berry juice — though that probably won’t change how anyone markets it.

Nuts That Aren’t Actually Nuts

While we’re destroying everything you thought you knew about food classification, let’s talk about nuts that aren’t really nuts. Peanuts, for instance, are actually legumes related to peas and beans, not nuts at all. Cashews, Brazil nuts, and pine nuts also fail the botanical definition of true nuts. A real nut is a hard-shelled fruit that doesn’t split open when ripe, with the seed fused to the fruit wall. Only a few foods we call nuts actually qualify: hazelnuts, chestnuts, and acorns are examples of true nuts. This means your “mixed nuts” snack mix is mostly seeds, legumes, and drupes masquerading as nuts. The botanical world really loves to mess with our heads.

Stone Fruits: The Drupe Family

Peaches, plums, cherries, and apricots belong to a completely different category called drupes, not berries. These fruits have a hard pit (or stone) in the center surrounded by soft flesh, which comes from a single ovary. The key difference is that drupes have three distinct layers: the outer skin, the fleshy middle, and the hard inner shell protecting the seed. Coconuts are actually the ultimate drupe, with their fibrous outer layer, hard shell, and single seed inside. Even olives fall into this category, making olive oil technically a fruit oil extracted from drupes. The drupe family shows just how diverse fruit structures can be, even when they all start from the same basic flower parts.

Apples and Pears: The Pome Pretenders

Apples and pears represent another fascinating category called pomes, which develop in a completely different way from berries. The fleshy part we eat doesn’t come from the ovary wall — instead, it develops from the receptacle tissue surrounding the flower, similar to strawberries but organized differently. The actual fruit is the core containing the seeds, while everything else is technically accessory tissue. This is why apple cores seem so distinct from the rest of the fruit; they’re literally different structures that grew together. Pears follow the same pattern, making both of these popular fruits botanical oddities that don’t fit neatly into the berry category despite their fleshy appearance.

The Avocado Berry Surprise

Avocados are berries, and this might be the most shocking revelation yet for anyone who’s ever put one in a salad or made guacamole. They develop from a single flower with one ovary, the creamy flesh comes from the ovary wall, and that giant seed in the middle fits perfectly into the berry definition. The high fat content and savory flavor fool us into thinking of avocados as vegetables, but botanically speaking, they’re large, single-seeded berries. This makes avocado toast a berry-on-grain breakfast, though that description probably won’t catch on at trendy cafes. The avocado’s berry status proves that botanical classification has nothing to do with taste, texture, or culinary use.

Why These Classifications Matter

Understanding botanical classifications isn’t just academic trivia — it actually helps scientists study plant evolution, breeding, and relationships between different species. When botanists know that tomatoes and potatoes are related (both in the nightshade family), they can better understand their shared characteristics and potential breeding possibilities. These classifications also help in agriculture, where knowing the true relationships between plants can improve growing techniques and pest management. For plant breeders trying to create new varieties, understanding whether they’re working with berries, drupes, or pomes gives them insight into what’s genetically possible. The confusion between common names and scientific classifications happens because language evolved differently than scientific understanding.

The Evolution of Fruit Names

Common fruit names developed over thousands of years based on appearance, taste, and cultural traditions, long before anyone understood plant biology. The word “berry” originally just meant “small, round fruit,” which explains why we use it for strawberries and raspberries that don’t meet the botanical definition. Scientists later needed precise terminology to study and classify plants accurately, leading to the technical definitions that seem so counterintuitive today. Different cultures also developed their own naming systems, which is why the same fruit might have completely different names and associations around the world. This linguistic evolution explains why grocery store categories make perfect sense for shopping but no sense for botany.

How Fruits Actually Develop

The real magic happens in the flower, where all these different fruit types begin their journey in remarkably similar ways. Every fruit starts as a flower with male and female parts, but the number and arrangement of ovaries determines what kind of fruit will develop. Single ovary flowers can become berries, drupes, or pomes depending on how the ovary wall and surrounding tissues develop. Multiple ovary flowers create aggregate fruits like raspberries, while multiple flowers can fuse together to create compound fruits like pineapples. Understanding this process reveals why botanical classification focuses on reproductive structures rather than the final appearance or taste of the fruit.

The Pineapple Plot Twist

Just when you think you’ve got fruit classification figured out, along comes the pineapple to blow your mind again. Pineapples aren’t berries, aggregate fruits, or any single fruit at all — they’re actually a fusion of multiple fruits from multiple flowers all growing together on one stem. Each of those diamond-shaped sections on a pineapple’s surface represents a separate flower that contributed to the final fruit. This makes pineapples “compound fruits” or “multiple fruits,” putting them in their own special category. The spiky crown on top isn’t just decoration; it’s actually a shortened stem with leaves that can be planted to grow a new pineapple plant. So when you’re eating pineapple, you’re technically eating dozens of fused fruits all at once.

What This Means for Your Kitchen

Does knowing that bananas are berries change how they taste? Absolutely not. Will this information make your strawberry shortcake any less delicious? Definitely not. But understanding these classifications can give you a new appreciation for the incredible diversity of plant reproductive strategies and the complexity hiding behind seemingly simple fruits. The next time you’re at the grocery store, you can amaze friends by pointing out all the berries hiding in plain sight — tomatoes, cucumbers, grapes, and yes, bananas. This knowledge connects us to the fascinating world of botany and reminds us that nature is far more creative and surprising than our everyday categories suggest.

The botanical world doesn’t care about our culinary traditions or common sense — it follows the logic of plant reproduction and evolution. While strawberries will always taste like summer and bananas will remain the perfect portable snack, now you know the surprising science behind their classifications. These revelations remind us that the natural world is full of unexpected connections and relationships that challenge our assumptions. Next time someone confidently states that strawberries are berries, you’ll have the delightful opportunity to share one of nature’s most entertaining contradictions. Who knew that understanding fruit could be so mind-bending?