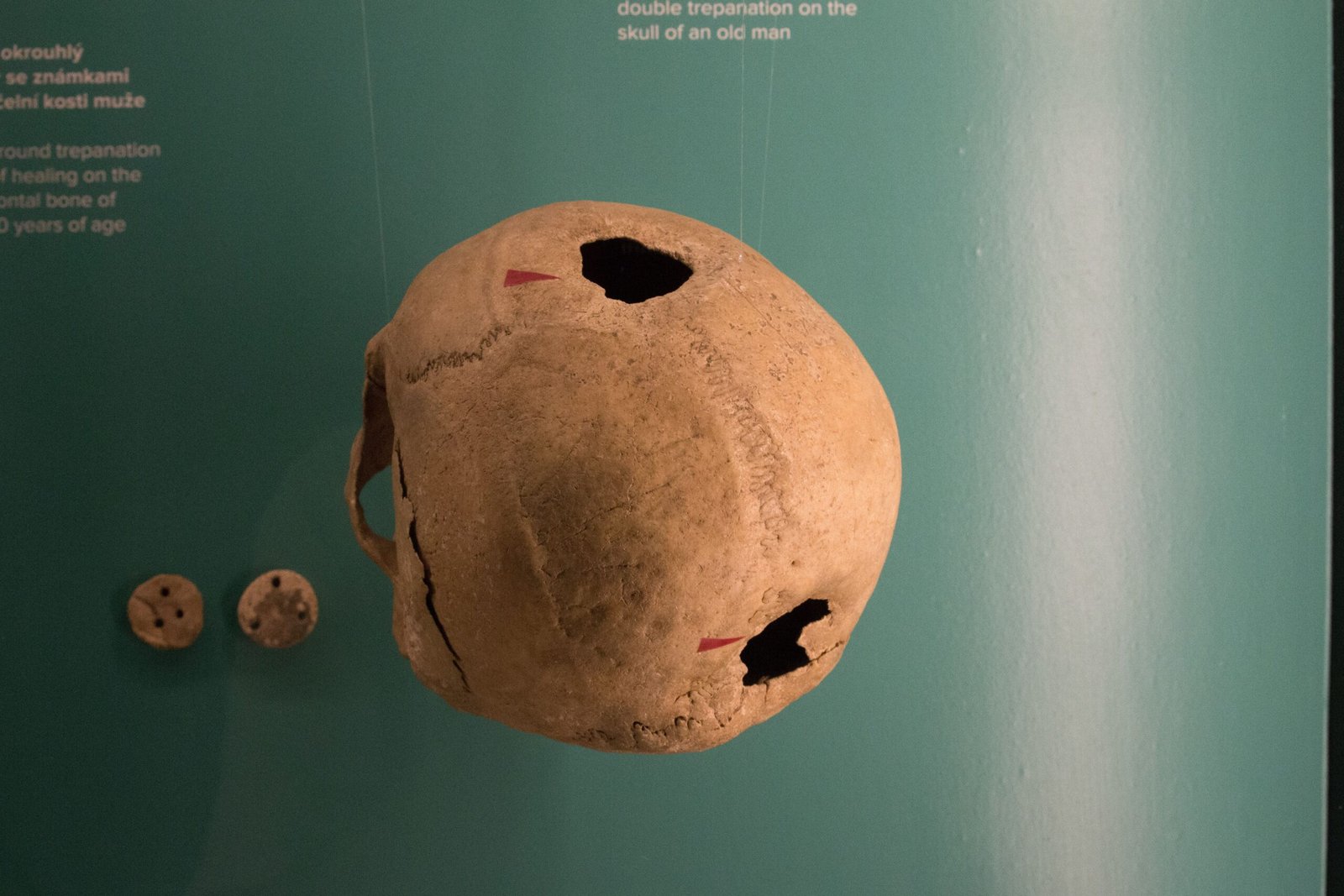

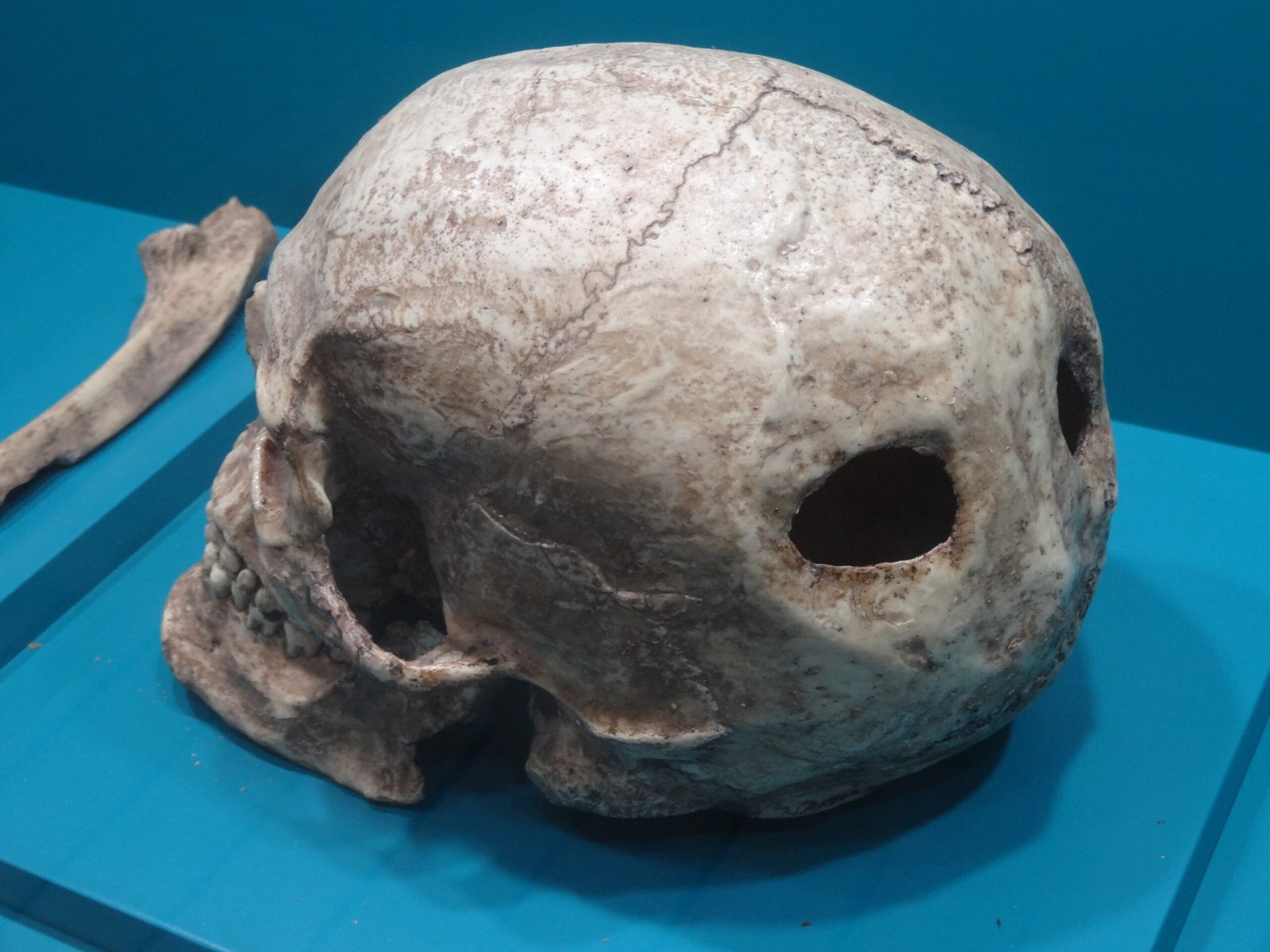

Picture this: archaeologists carefully brush away centuries of dirt from a human skull, only to discover something that makes their hearts race. A perfectly circular hole, smooth around the edges, stares back at them from the ancient bone. The question that immediately springs to mind is both fascinating and terrifying: did someone drill into this person’s head while they were still alive?

The Mystery of Trepanation Revealed

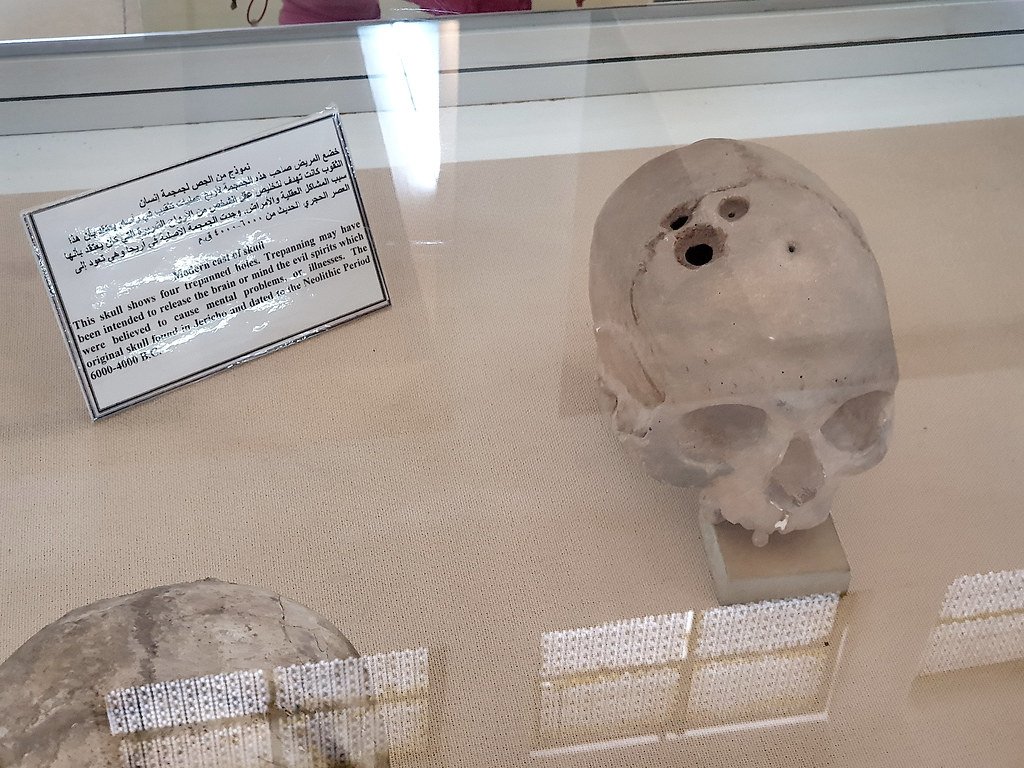

Trepanation, the ancient practice of drilling holes into the skull, represents one of humanity’s oldest surgical procedures. Archaeological evidence shows that our ancestors were performing this daring operation as far back as 6500 BCE, making it older than Stonehenge itself.

The procedure involved using primitive tools like obsidian blades, bronze instruments, or even sharpened stones to carefully remove sections of the skull. What’s truly remarkable is that many of these ancient patients survived the ordeal, as evidenced by healing patterns around the holes.

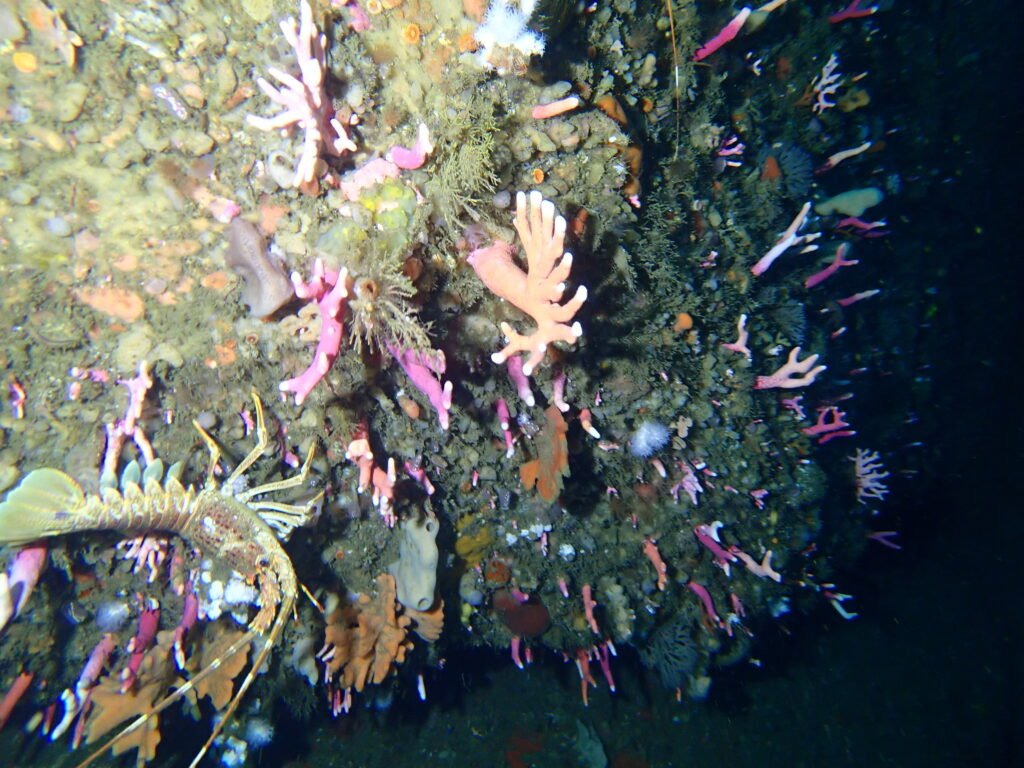

The practice wasn’t limited to one civilization or continent. From the mountains of Peru to the steppes of Russia, from ancient Egypt to medieval Europe, trepanation was performed across cultures that had no contact with each other.

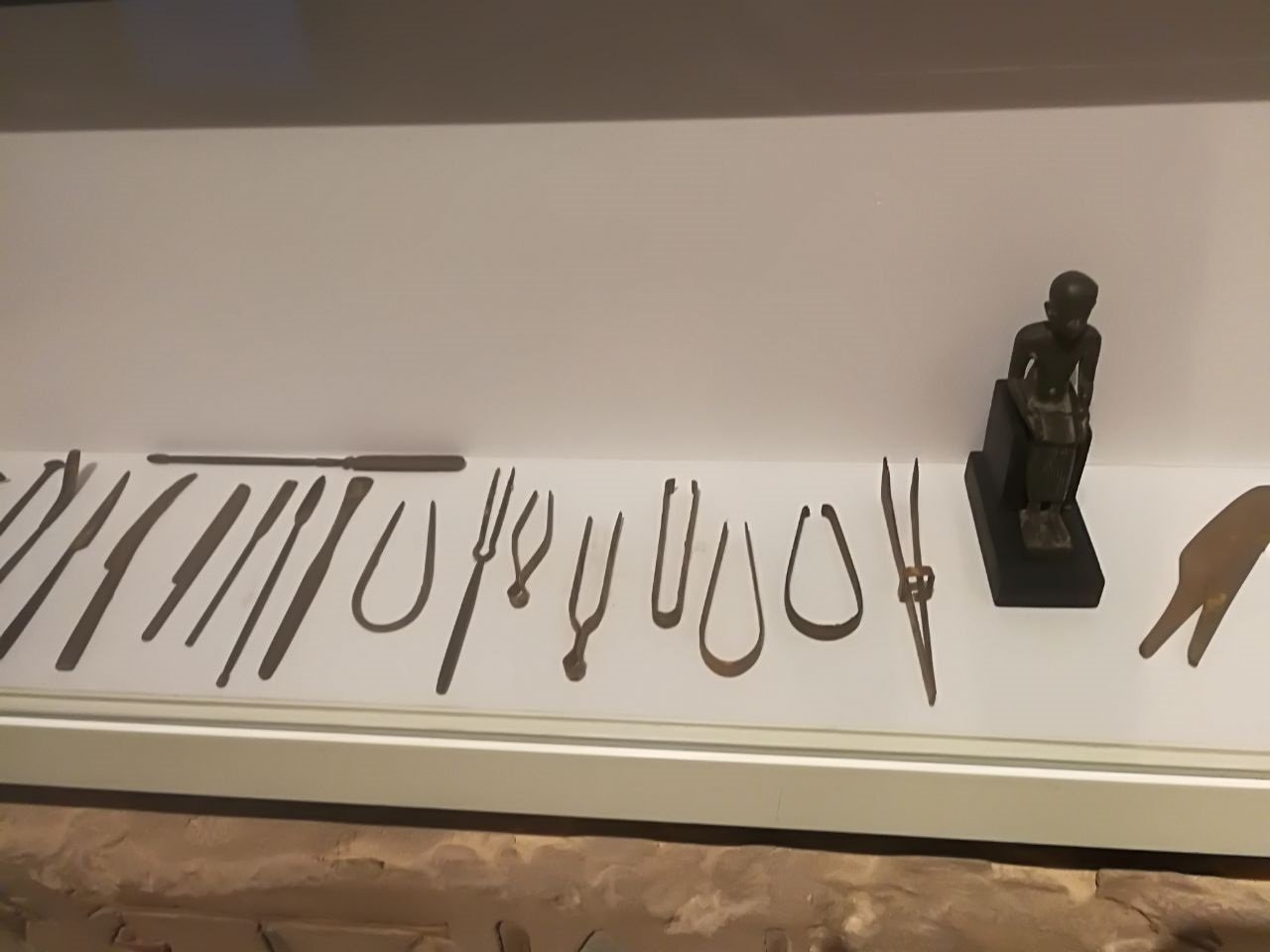

Ancient Tools of the Trade

The surgical instruments used by ancient practitioners were surprisingly sophisticated for their time. Obsidian scalpels, sharper than modern steel blades, could create precise cuts with minimal tissue damage. Bronze and copper tools provided durability for the drilling process.

Archaeological discoveries have revealed complete surgical kits from various civilizations. The Inca used tumi knives made of precious metals, while European medieval surgeons employed specialized trepans with serrated edges.

These tools required incredible skill to use effectively. The surgeon had to maintain steady pressure while avoiding the brain tissue beneath, all without modern anesthesia or antibiotics.

Survival Rates That Defy Logic

Perhaps the most shocking aspect of ancient trepanation is how many patients actually survived. Studies of prehistoric skulls show survival rates ranging from 50% to 90%, depending on the time period and location.

Evidence of survival comes from bone regrowth around the surgical sites. When bone shows signs of healing, it indicates the patient lived for weeks, months, or even years after the procedure. Some skulls display multiple trepanation sites, suggesting repeat procedures on the same individual.

The Inca civilization achieved particularly impressive survival rates, with some studies suggesting up to 90% of patients survived their cranial surgeries. This success rate rivals some modern surgical procedures, making it all the more remarkable given their primitive conditions.

Medical Reasons Behind the Drill

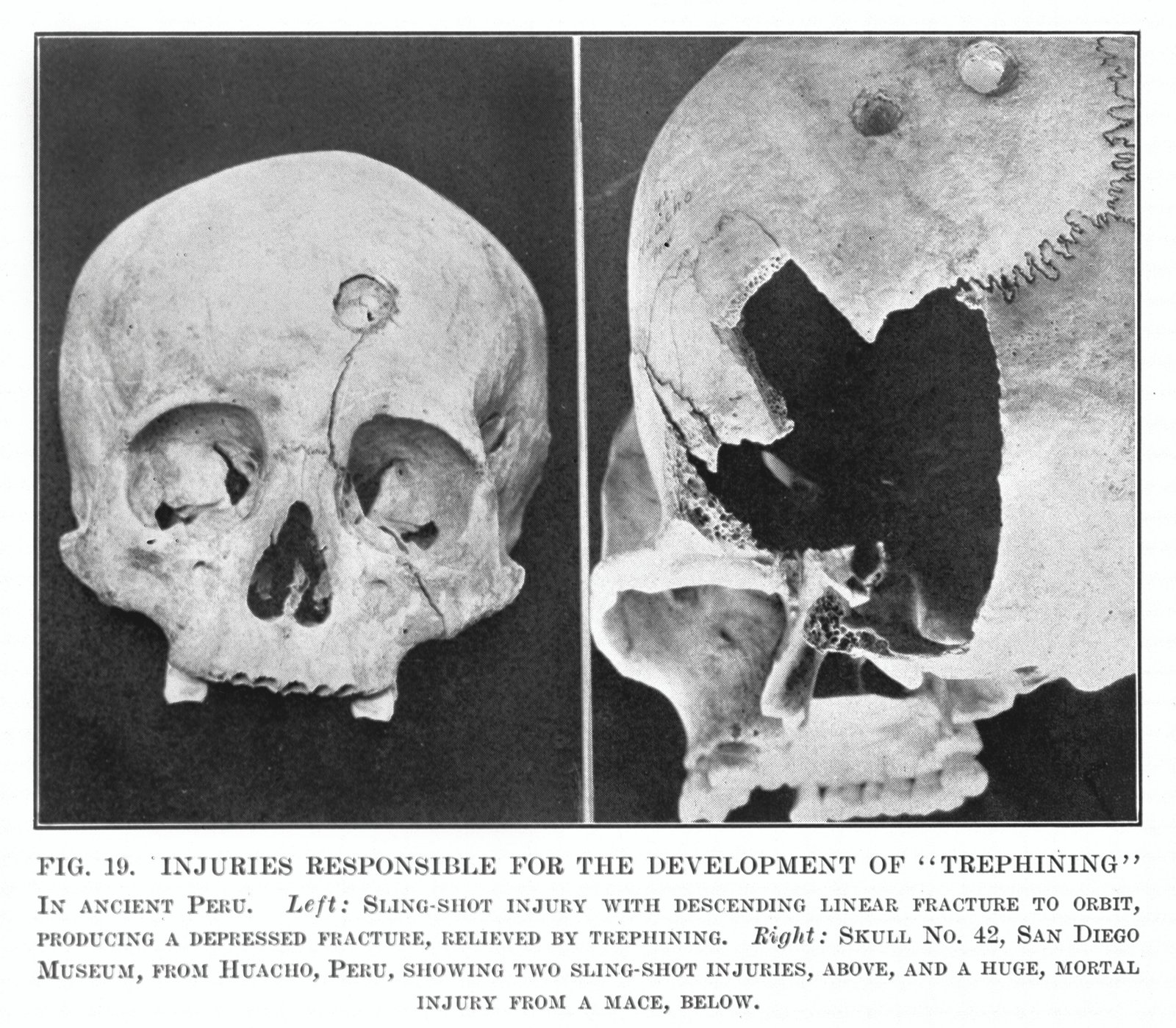

Ancient surgeons didn’t perform trepanation on a whim. Medical evidence suggests they understood specific conditions that could benefit from cranial surgery. Head injuries from warfare or accidents were common reasons for the procedure, as surgeons attempted to relieve pressure from blood clots or bone fragments.

Skull fractures, particularly depressed fractures where bone pieces pressed against the brain, were prime candidates for trepanation. Archaeological evidence shows many skulls with clear trauma patterns that led to surgical intervention.

Chronic headaches, seizures, and what we might now recognize as brain tumors may have also prompted ancient surgeons to reach for their drilling tools. While they couldn’t understand the neurological basis of these conditions, they observed that relieving cranial pressure sometimes provided relief.

Spiritual and Ritualistic Motivations

Not all trepanation was medically motivated. Many ancient cultures believed that drilling holes in the skull could release evil spirits or allow good spirits to enter the body. This spiritual dimension added another layer of complexity to the practice.

In some societies, trepanation was performed as a rite of passage or to enhance spiritual abilities. Warriors might undergo the procedure to gain courage, while shamans believed it could open their minds to divine communication.

The placement of holes sometimes followed specific patterns that align with spiritual beliefs rather than medical necessity. Skulls found in ceremonial contexts often show trepanation holes in locations that correspond to ancient concepts of spiritual energy centers.

Geographic Distribution Across Continents

The practice of trepanation spread across virtually every inhabited continent, suggesting either independent development or very early cultural exchange. South America, particularly Peru, has yielded the highest concentration of trepanned skulls, with some sites containing hundreds of specimens.

European trepanation sites span from Neolithic Britain to medieval Germany, showing continuous practice across millennia. Each region developed its own techniques and tools, adapted to local materials and medical traditions.

Africa, Asia, and Oceania have also produced evidence of ancient cranial surgery, though in smaller numbers. The global distribution of this practice highlights humanity’s universal struggle with head injuries and neurological conditions.

The Peruvian Masters of Skull Surgery

The ancient Peruvian civilizations, particularly the Inca and their predecessors, elevated trepanation to an art form. Their surgical techniques were so advanced that they achieved success rates comparable to modern neurosurgery, despite lacking antibiotics, anesthesia, or sterile environments.

Peruvian surgeons developed multiple techniques for skull removal, including scraping, cutting, and drilling. They understood the importance of creating smooth edges to promote healing and minimize infection risk.

The Paracas culture, which flourished from 800 to 100 BCE, left behind over 250 trepanned skulls. Many show signs of multiple procedures, indicating that patients not only survived but returned for additional surgeries. Some individuals underwent as many as five separate trepanations during their lifetime.

Evidence of Anesthesia and Pain Management

While ancient surgeons lacked modern anesthetics, they weren’t completely helpless against pain. Archaeological and botanical evidence suggests they used various plant-based substances to numb pain and calm patients during surgery.

Coca leaves, containing natural cocaine, were commonly used in South American trepanation procedures. The leaves could be chewed to provide local numbing effects, while fermented beverages made from the same plants offered systemic pain relief.

European practitioners likely used opium poppies, mandrake root, or alcohol-based concoctions. These substances, while primitive by modern standards, provided enough pain relief to make the surgery tolerable for conscious patients.

Infection Control in Ancient Times

The high survival rates of ancient trepanation procedures suggest that early surgeons understood at least basic principles of infection control. They may not have known about bacteria, but they recognized the importance of clean tools and proper wound care.

Many ancient cultures used honey as a wound dressing, which we now know has natural antibacterial properties. Silver implements, when available, provided additional antimicrobial benefits that ancient surgeons may have recognized empirically.

The practice of cauterizing wounds with hot metal tools also helped prevent infection, though this was likely discovered through trial and error rather than scientific understanding. These techniques, combined with the body’s natural healing abilities, contributed to surprisingly high success rates.

Modern Forensic Analysis Techniques

Today’s scientists use advanced techniques to study ancient trepanned skulls, revealing details that would have been impossible to detect just decades ago. CT scans and 3D imaging allow researchers to examine bone healing patterns without damaging the specimens.

Microscopic analysis of bone edges can determine whether the person was alive during the procedure by examining cellular activity patterns. Chemical analysis of bone can reveal information about the person’s diet, health status, and even the tools used in the surgery.

Carbon dating and DNA analysis provide additional context about the age, sex, and ancestry of trepanned individuals. These modern techniques are revolutionizing our understanding of ancient surgical practices and their outcomes.

Gender and Age Patterns in Ancient Surgery

Analysis of trepanned skulls reveals interesting patterns regarding who received these procedures. Adult males dominate the archaeological record, likely reflecting their higher exposure to warfare and dangerous occupations that resulted in head injuries.

However, women and children were also subjects of trepanation, though in smaller numbers. Female skulls sometimes show trepanation holes in patterns that suggest ritualistic rather than medical motivations, possibly related to spiritual or shamanistic practices.

The age distribution varies by culture and time period. Some societies performed trepanation primarily on young adults, while others included elderly individuals. Children’s skulls with trepanation holes are relatively rare, suggesting that the procedure was typically reserved for adults who could better survive the trauma.

Comparison with Modern Neurosurgery

While ancient trepanation was crude by today’s standards, it shares fundamental principles with modern neurosurgery. Both involve creating controlled access to the brain to relieve pressure, remove damaged tissue, or address medical conditions.

Modern craniotomy procedures follow similar basic steps: creating an opening in the skull, addressing the underlying problem, and closing the wound. The main differences lie in precision, sterility, and post-operative care rather than fundamental surgical concepts.

What’s truly remarkable is that ancient surgeons achieved their results without understanding brain anatomy, bacterial theory, or modern medical principles. Their success relied on careful observation, skilled hands, and accumulated knowledge passed down through generations.

The Role of Shamans and Healers

In many ancient cultures, trepanation was performed by shamans or specialized healers rather than what we might consider traditional surgeons. These individuals combined medical knowledge with spiritual beliefs, viewing the procedure as both physical and metaphysical healing.

Shamanic trepanation often involved elaborate rituals designed to protect the patient and ensure successful outcomes. These ceremonies might include prayers, offerings, and the use of sacred tools that were believed to possess special powers.

The dual role of surgeon and spiritual guide meant that these practitioners held enormous responsibility and respect within their communities. Their success with trepanation likely enhanced their status and influence, creating a positive feedback loop that encouraged further development of surgical skills.

Archaeological Sites and Notable Discoveries

Some of the most significant trepanation discoveries come from specific archaeological sites that have yielded multiple specimens. The Jericho site in the Jordan Valley produced skulls dating back 9,000 years, representing some of the earliest evidence of human cranial surgery.

The Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico has revealed numerous trepanned skulls from Ancestral Puebloan cultures, showing sophisticated surgical techniques developed independently in North America. These findings demonstrate that trepanation was practiced across diverse Native American cultures.

European sites like the Ensisheim skull from France and various British Neolithic sites provide evidence of continuous trepanation practices throughout European prehistory and into historical times. Each discovery adds new pieces to the puzzle of ancient surgical practices.

Controversies and Debates in the Field

Not all researchers agree on the interpretation of trepanned skulls. Some argue that certain holes attributed to surgery were actually caused by post-mortem damage or natural processes. Distinguishing between intentional trepanation and accidental hole formation requires careful analysis of bone edges and healing patterns.

The motivation behind specific trepanation procedures remains debated. While some cases clearly show medical necessity, others appear to have been performed on healthy individuals, leading to disagreements about whether the procedure was medical, ritualistic, or both.

Success rates are another contentious topic. While healing patterns indicate survival, determining how long patients lived after surgery and their quality of life remains challenging. Some researchers argue that survival rates may be overestimated based on available evidence.

Cultural Variations in Technique

Different cultures developed unique approaches to trepanation, reflecting local beliefs, available materials, and accumulated knowledge. The Inca preferred rectangular holes created through careful scraping, while European practitioners often used circular drilling techniques.

Some cultures created multiple small holes rather than single large openings, possibly to minimize trauma while still achieving the desired pressure relief. Others developed specialized tools for specific types of cranial surgery, showing remarkable innovation given their technological limitations.

The aftercare practices also varied significantly between cultures. Some societies used elaborate bandaging systems, while others relied on simple coverings. These variations provide insights into different medical traditions and their understanding of wound healing.

Legacy and Modern Implications

The study of ancient trepanation has contributed valuable insights to modern medical practice. Understanding how early surgeons achieved success without modern tools has influenced current approaches to emergency neurosurgery in resource-limited settings.

Some traditional trepanation techniques are being reconsidered for their simplicity and effectiveness. In situations where modern surgical equipment isn’t available, ancient methods might provide life-saving alternatives for treating head injuries.

The psychological and social aspects of ancient surgery also inform modern medical practice. The role of ritual and community support in healing, demonstrated by ancient trepanation practices, has influenced contemporary approaches to patient care and surgical procedures.

Future Research Directions

Advanced imaging technologies continue to reveal new information about ancient trepanation procedures. Researchers are developing new methods to analyze bone healing patterns and determine more precise survival rates and post-operative outcomes.

Genetic analysis of ancient DNA may provide insights into the health conditions that led to trepanation, potentially identifying specific diseases or genetic predispositions that made certain individuals candidates for cranial surgery.

Experimental archaeology, where researchers recreate ancient surgical techniques using period-appropriate tools and methods, is providing new understanding of the challenges and skills required for successful trepanation. These studies help bridge the gap between archaeological evidence and practical surgical reality.

The practice of trepanation represents a remarkable chapter in human medical history, demonstrating that our ancestors possessed sophisticated surgical knowledge and techniques thousands of years before modern medicine emerged. These ancient surgeons, working without anesthesia, antibiotics, or detailed anatomical knowledge, achieved survival rates that rival some contemporary procedures. Their success challenges our assumptions about primitive medical practices and highlights the ingenuity of early human problem-solving. The global distribution of trepanation shows that confronting head injuries and neurological conditions was a universal human challenge, met with remarkably similar solutions across isolated cultures. As we continue to study these ancient skulls with their telltale holes, we gain not only historical insight but also practical knowledge that might inform modern medical practice in resource-limited settings. What does it say about human nature that our ancestors were willing to drill holes in each other’s heads, and somehow make it work?