The question of whether machines should have gender identity has become one of the most fascinating and contentious discussions in our digital age. As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly sophisticated and humanlike, we’re unconsciously assigning gender roles to our technological companions in ways that reveal deep-seated biases about who we are as a society. The implications stretch far beyond simple preference—they could reshape how future generations understand gender, power, and social interaction.

The Feminine Voice Revolution

Walk into any modern home and you’ll likely encounter a digital assistant speaking in a distinctly feminine voice. Siri, Alexa, and Cortana all default to female-sounding voices for a reason—most people prefer them. This isn’t coincidence or marketing accident. An Amazon spokesperson revealed that test users for Alexa responded most strongly to a female voice, while Microsoft found female voices best embodied the qualities they wanted in Cortana—helpful, supportive, and trustworthy. But here’s the twist: text-to-speech systems were historically trained mostly on female voices, making female AI voices technically easier to create. Sometimes our biases become self-reinforcing through pure technological momentum.

The preference for feminine AI voices taps into something deeper than mere acoustic pleasure. Research shows people find female-perceived voices “warm,” and both men and women demonstrate preferences for women’s voices. Yet this warmth comes with a troubling undertone. UNESCO’s 2019 report argued that feminine voice assistants reinforce biases that women are “subservient and tolerant of poor treatment,” sending signals that women are “obliging, docile and eager-to-please helpers”. We’re essentially teaching our children that helpful voices should sound like women.

When Machines Learn Our Worst Habits

The way we interact with gendered AI reveals uncomfortable truths about human behavior. New research from Johns Hopkins shows that men interrupt female-voiced AI assistants almost twice as often as women do. This mirrors real-world patterns where studies have long shown men are more likely to interrupt, particularly when speaking with women. The scary part? Children pick up these patterns, potentially learning that “this is the way you talk to someone and this is maybe the way you talk to women”. We’re accidentally programming the next generation’s social scripts.

The harassment problem goes even deeper. A 2017 study found that voice assistants often responded to sexual comments with ambiguous or even thankful replies, with Siri suggesting that similar queries might be “meant to be applied to other assistants”. By 2020, most responses had changed to be more condemning of harassing speech, but the damage was already done. Millions of users had learned they could speak abusively to feminine-coded machines without consequence.

The Gender Projection Phenomenon

Humans seem hardwired to assign gender to anything that interacts with us socially. Whether as designers or users, we tend to gender machines because gender is a primary social category in human cultures, and as soon as users assign gender to a machine, stereotypes follow. This isn’t limited to voice assistants. Research shows that even gender-neutral robots can be assigned gender depending on the actions they perform. A robot performing traditionally “masculine” tasks like construction work gets perceived as male, while one organizing or cleaning gets seen as female.

The implications are staggering. Customer-facing service robots worldwide feature gendered names, voices, or appearances, with major US voice assistants collectively holding 92.4% of market share and traditionally featuring female-sounding voices. We’re not just creating tools—we’re creating a parallel social hierarchy where artificial beings assume traditionally gendered roles. As one researcher noted, “it’s inherent in our ability to relate to the world that we start to apply these known social constructs in various things,” including robots and conversational AIs.

The Authority Voice Paradox

Here’s where things get really interesting: the gender of AI voices changes based on their role. On city streets and in subways, you’re more likely to hear male automated voices giving commands, because lower-pitched voices are typically deemed more authoritative and influential. In the past, most voices giving commands were male while assistance voices were female, though recent efforts have created more of a mix. Think about it—we literally program our machines to reflect our cultural assumptions about who should give orders and who should take them.

The cultural variations are revealing too. In Great Britain, Siri launched with a male voice, possibly because “the British have always had male servants,” evoking “the stereotype of the always helpful, always present valet”. In Germany, BMW’s female-voiced GPS system triggered complaints from male customers who didn’t want a woman telling them what to do. Our biases literally cross borders and reshape technology in different markets.

The Rise of AI Gender Bias

The problem extends far beyond voice preferences into the core of how AI systems make decisions. A Berkeley Haas Center study analyzed 133 AI systems across industries and found that 44% showed gender bias, while 25% exhibited both gender and racial bias. When asked to write a story about a doctor and nurse, generative AI consistently made the doctor male and nurse female, regardless of repeated prompts challenging this pattern. The machines aren’t being deliberately sexist—they’re reflecting the biased data they were trained on.

If AI is trained on data that associates women and men with different skills or interests, it will generate content reflecting that bias, essentially mirroring “the biases that are present in our society and that manifest in AI training data”. Amazon famously discontinued an AI recruitment tool in 2018 that favored male resumes, while image recognition systems have struggled to accurately identify women, particularly women of color, leading to potentially serious consequences in law enforcement. We’re building tomorrow’s decision-makers on yesterday’s prejudices.

The Gender Data Gap

Women are notably underrepresented in AI development, which compounds the bias problem. Women contribute to roughly 45% of AI publications worldwide, but only 11% of AI publications are authored solely by women, while 55% are penned by men alone. There’s a critical need for diverse expertise when developing AI, including gender expertise, because “the lack of gender perspectives, data, and decision-making can perpetuate profound inequality for years to come”. When mostly men design systems that affect everyone, the results inevitably reflect masculine perspectives and priorities.

The usage gap is equally concerning. Recent Federal Reserve research revealed a significant “gen AI gender gap”—50% of men report using generative AI over the previous twelve months compared to only 37% of women. The gap isn’t driven by demographics like income or education, but by knowledge about AI and concerns about privacy and trust. If women are less likely to use AI tools, they’re also less likely to influence their development or benefit from their capabilities.

The Trust Deficit

Gender differences in AI trust run deeper than simple preference. Among generative AI users, only 34% of women use the technology daily compared to 43% of men, and just 41% of women feel AI substantially boosts their productivity versus 61% of men, with women consistently showing lower levels of trust. Among AI experts, men are far more likely than women to predict positive outcomes from AI (63% vs 36%), while female experts are more likely to predict negative outcomes or mixed results. Women aren’t being pessimistic—they’re being realistic about systems that weren’t designed with their needs in mind.

Men are consistently more optimistic about AI’s potential, particularly in areas like medical care, and are more likely to trust AI to make decisions for them. This trust gap could become a feedback loop where masculine-designed systems continue to work better for men, reinforcing women’s skepticism and reducing their participation in shaping AI’s future. The result? Technology that increasingly serves half the population while alienating the other half.

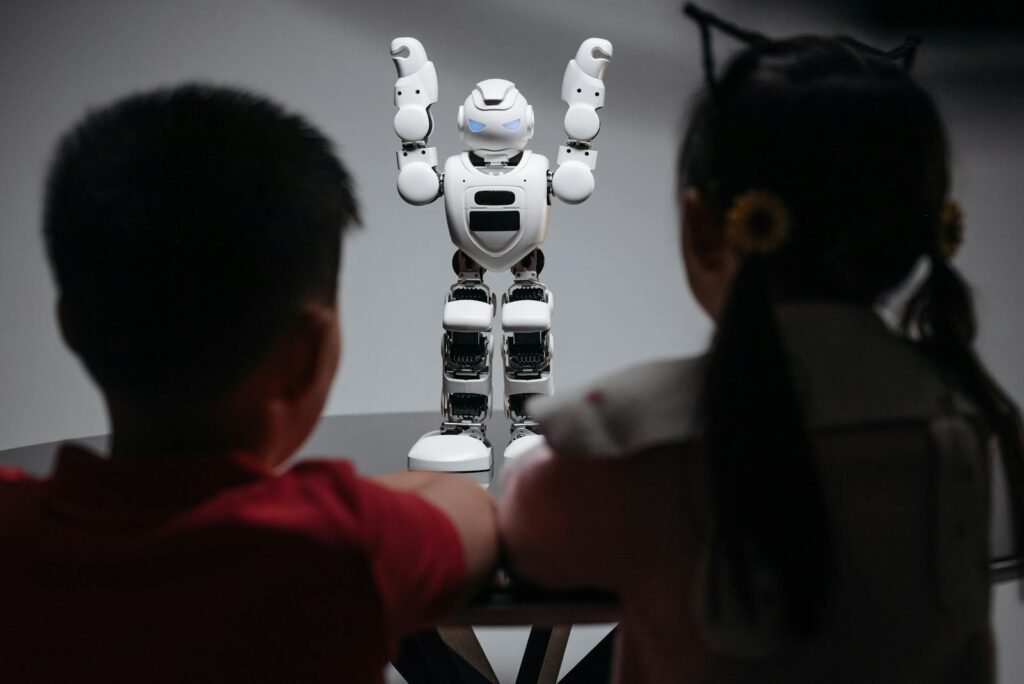

Robots and Gender Stereotypes

Physical robots present even more complex gender projection challenges. Research shows that artificial robot faces that appear feminine and humanlike are judged as warmer and produce higher levels of comfort, resulting in more positive evaluations. Robots are characterized by their physicality, making it easy for humans to assign gender arbitrarily, creating problems with “gendered robots” that should be carefully examined. We’re literally sculpting our biases into metal and silicon.

The interactions reveal fascinating patterns. In experiments where participants cooperated with robots having gendered voices and names, a “cross-gender effect” emerged—people felt more comfortable interacting with robots of a different gender than their own. Male participants consistently rated robots higher on measures of warmth, liking, and contact desirability, though these effects didn’t vary between men and women for specific robot types. Our comfort with artificial beings mirrors our complex relationships with real people.

The Corporate Contradiction

Tech companies find themselves in an impossible position, simultaneously acknowledging and denying their AI’s gender identity. All four major voice assistants—Siri, Alexa, Cortana, and Google Assistant—decline to acknowledge any gender identity, with responses ranging from “I don’t have a gender” to “I’m AI, which means I exist outside of gender”. Yet even these “genderless” assistants come with historically female-sounding default voices.

Amazon’s internal guidelines for Alexa perfectly capture this contradiction—they state that Alexa “does not have a gender” and shouldn’t be labeled with pronouns like “she” and “her,” but later in the same document refer to Alexa as “she” and describe her “female persona”. The guidelines reveal the fundamental problem of trying to give machines gendered human identities—if AI speaks like a woman and has a “female persona,” people will naturally make associations with actual women. You can’t have it both ways.

The Gender-Neutral Alternative

Some researchers and companies are pioneering gender-neutral AI voices. A coalition of activists and engineers created “Q,” claimed to be the first genderless AI voice, declaring “I’m created for a future where we are no longer defined by gender, but rather how we define ourselves”. To create Q, sound engineers recorded 24 people of various gender identities and modified voices to fall within a 145-175 Hz gender-neutral frequency range. Testing with 4,500 participants found that 50% perceived the voice as neutral, 26% as masculine, and 24% as feminine.

Research shows that gender-neutral voice assistants that apologize for mistakes reduce impolite interactions and interruptions, even though they’re perceived as less warm and more “robotic,” suggesting that “designing virtual agents with neutral traits has the potential to foster more respectful interactions”. Companies like GoDaddy and Lowe’s are experimenting with gender-neutral chatbots, with Lowe’s creating a character simply called “Grill Master” to help customers. The future might sound different than we expect.

Cultural Reflections in Code

Designers of robots and AI don’t simply create products that reflect our world—they also reinforce and validate certain gender norms considered appropriate for different people. One way forward is projecting voice assistants as non-humans—a “let’s keep AI artificial” approach that uses voices that are “clear, distinct and pleasant, but still immediately recognizable as non-human and not overtly male or female”. If companies want to avoid tricky gender questions, there’s no rule that AI assistants have to be “cast” as young women or men—makers would do well to embrace the non-human identity of their creations.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. With 4.2 billion virtual assistants in use worldwide and none having physical human appearance, most Americans would likely assign female gender to their virtual assistant, thanks to the feminine names and voices of systems like Siri, Alexa, and Cortana. Digital assistants are expected to outnumber humans within three years, with 36% of parents reporting their children under 12 use voice assistants, including 14% of children aged 0-2. We’re literally programming the next generation’s understanding of gender roles.

The Uncanny Valley of Gender

The push for more humanlike AI creates what we might call a “gender uncanny valley”—the more humanlike our machines become, the more uncomfortable we grow with their ambiguous gender status. Defining social robots as “humanoid” implies they should be perceived similarly to people, with designers often relying on human-human interactions as models, though robots’ social capacities remain relatively primitive. There’s an ethical problem with humanizing robots and encouraging human-like relationships with objects under human control, as users might develop social scripts with robots that could be applied to human interactions, potentially leading to objectification or mistreatment.

Recent research found that when robots are gendered at all, they’re significantly more often categorized as male than female across all domains—social, service, and industrial. This suggests a cross-domain male-robot bias rather than domain-specific stereotypes. As our AI becomes more sophisticated, we’re not transcending gender—we’re reinforcing it in new and potentially more problematic ways.

The Economic Implications

The gender dynamics of AI aren’t just social issues—they’re economic ones. The generative AI gender gap could amplify existing pay disparities, making privacy regulations and policies promoting AI-related knowledge and skills essential. AI has helped identify gender pay gaps and improve credit scoring fairness, while also improving access to microfinance for women entrepreneurs. The technology could either accelerate equality or entrench inequality, depending on how we design and deploy it.

In the United States, women are rapidly closing the AI adoption gap—the proportion who have adopted generative AI tripled in one year, outpacing men’s 2.2x growth rate, with projections showing women will match or surpass men’s usage by end of 2025. For women to reap AI’s full rewards, tech companies must work to increase trust, reduce bias, and strive for more representative workforces. The window for building inclusive AI is still open, but it won’t stay that way forever.