Sunrise crowds and afternoon beachgoers have noticed it: dorsal fins slicing through glossy swells from Florida to Cape Cod, showing up again and again where families swim and anglers cast. The pattern feels new, but the story stretches far deeper into the water column than a viral clip can show. Scientists are racing to decode why certain sharks keep returning to the same East Coast beaches, and what their persistence says about a changing ocean. This is not a simple tale of danger; it’s a layered mystery of migration corridors, rebounding prey, warming currents, and better technology. The result is a coastline learning to read the ocean in real time – one ping, drone flight, and tide shift at a time.

The Hidden Clues

At first light, the water looks empty – until a smear of baitfish tightens like a muscle and a darker shape tilts in from below. That’s often the real clue behind repeat shark appearances: dense schools of menhaden and mullet pushing close to shore on a rising tide, their silver bodies flashing like loose coins. When wind and current stack warm water against the beach and the bait funnels into troughs, sharks follow, not because people are present, but because the buffet is. Lifeguards and surfers see the rhythm as clearly as a tide chart: birds dive, bait pops, fins appear, then everything calms. The pattern can repeat over hours or days in the same pocket of beach, giving the impression that the same sharks keep “showing up,” when it’s really the grocery store that keeps opening its doors.

I’ve stood on a chilly New Jersey beach watching menhaden nervous on the sandbar while a gray shape traced the edge like a careful pen stroke. It felt dramatic, but the behavior was textbook: go where the calories are cheap and the water offers cover. Once the wind shifts or the bait moves offshore, those fins vanish as quickly as they came. In that sense, the daily tide schedule is as important as any high-tech tracker. Learn the cues – bird activity, bait density, clarity, and tide – and the surprise turns into a readable forecast.

From Fisherman Lore to Modern Science

Coastal fishers have long mapped shark seasons in stories passed on at bait shops and harbors, but today those maps carry time stamps and GPS tracks. Satellite tags fixed to dorsal fins beam locations to orbiting receivers, sketching migration highways that climb north in spring and slide south again in fall. Acoustic tags add finer detail: each ping is a check-in at underwater stations tucked along inlets, piers, and headlands, revealing which beaches act like shark rest stops. Drones widen the lens, spotting sharks beyond the break where lifeguard towers can’t see, while environmental DNA picks up microscopic traces of shark presence in a bottle of seawater. Together, these tools have turned rumors into routes and hunches into heat maps.

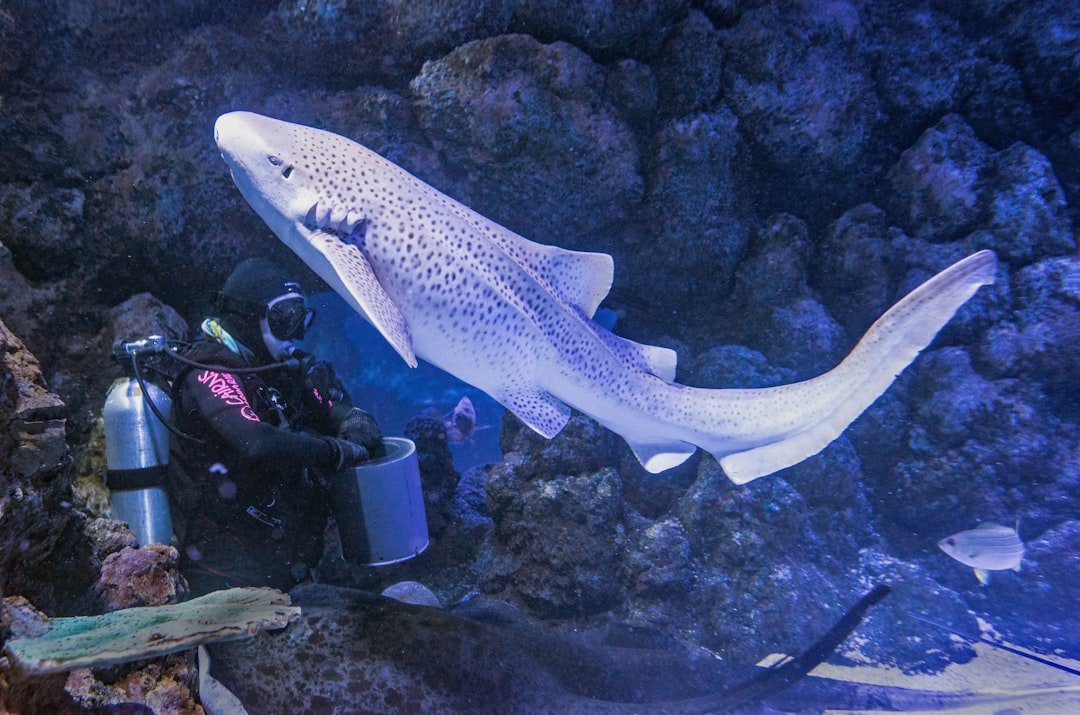

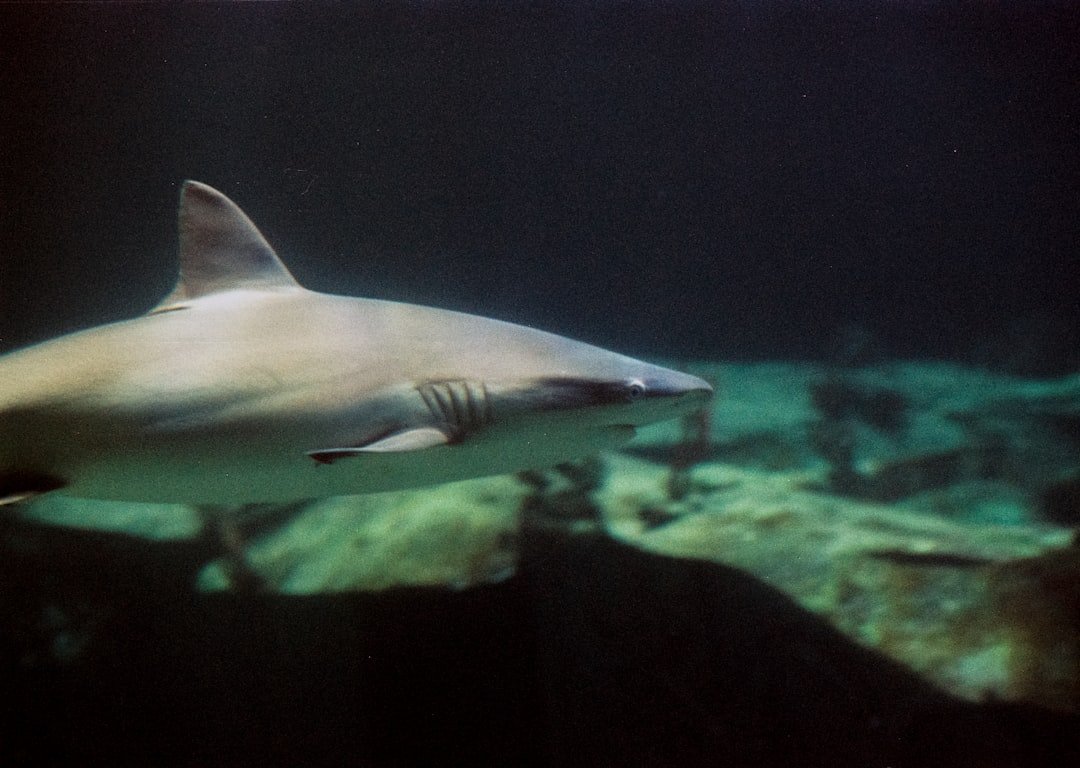

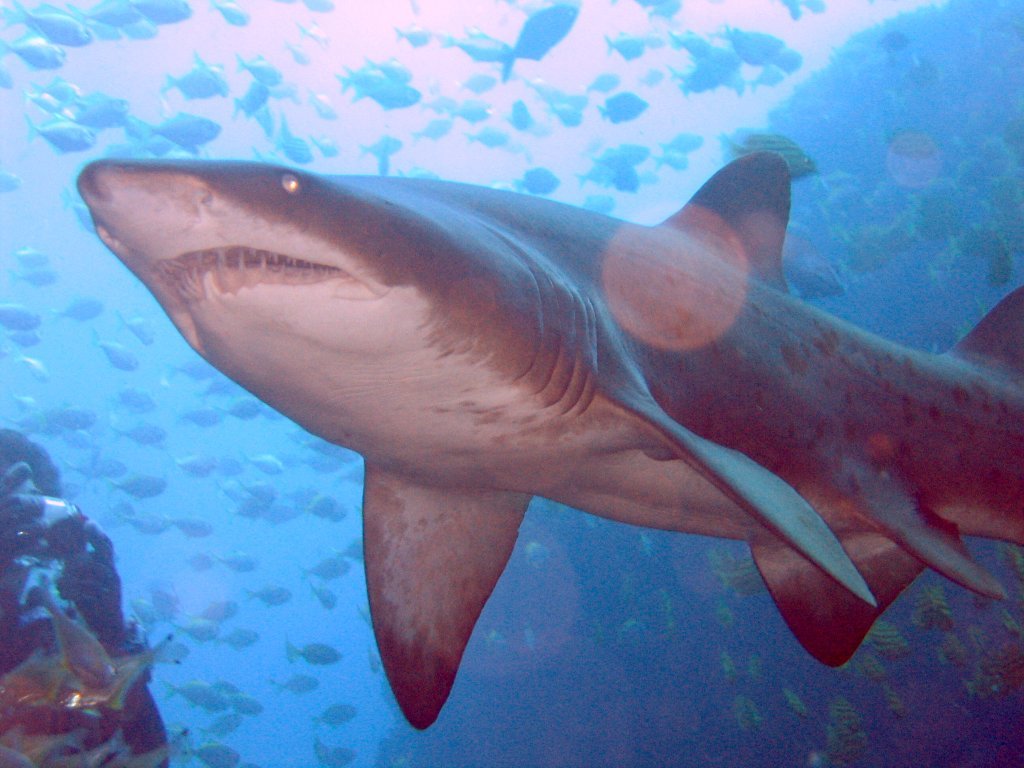

On a research skiff off the Carolinas, I watched a team work with brisk, practiced quiet, measuring, tagging, and releasing a juvenile sandbar shark in minutes. The science is careful because precision matters: was that a sandbar or sand tiger; did it return to the same inlet at the same stage of tide; did water temperature jump just enough to tip the migration? Across the East Coast, these small specifics are stitching a big picture that explains why some beaches see fins repeatedly while others rarely do. It’s not a single cause; it’s five or six levers moving at once. And when those levers align, the shoreline lights up with sharks.

The Usual Suspects Along Our Coasts

Different beaches host different visitors, and the roll call is changing with the seasons. In winter, blacktip sharks stack by the thousands along parts of Southeast Florida, chasing schools that bunch up like storm clouds over pale sand. Spring brings spinner sharks that cartwheel through bait lines, while sandbar and sand tiger sharks cruise the mid-Atlantic’s wrecks and shoals like careful inspectors. Farther north, the return of gray seals has attracted great white sharks to Cape Cod and, increasingly, to Long Island’s South Shore, where they often patrol deeper cuts beyond the last line of surfers. Bull and tiger sharks are more at home in warmer waters and estuaries, showing up near inlets and river mouths where salinity swings and food is diverse.

Most of these species aren’t zeroed in on people; they’re tuned to prey signals, water temperature, and structure. The challenge is that those same signals sometimes pile up right where swimmers gather – inside a trough beside a sandbar, near a jetty’s turbulent outflow, or around a bait line just past the breakers. If you keep seeing fins on your local beach, odds are the habitat is delivering something sharks value repeatedly, from predictable bait balls to current seams. That predictability is a gift for science, which needs repeat encounters to track trends. It’s also a reminder that beaches are not just playgrounds; they’re living edges of a vast food web.

Why They’re Closer Than Before

There’s no single switch that moved sharks toward shore, but several dials turned together. Conservation measures helped rebuild some prey, notably menhaden and seals in parts of the Northeast, effectively inviting predators back to historic hunting grounds. Warmer sea-surface temperatures and longer warm seasons expand suitable habitat, nudging species ranges north and compressing them against beaches when bait runs inside the surf zone. Coastal development and piers can create structure that concentrates prey, while fishing effort near shore often drifts near the same hotspots. And crucially, we’re simply better at seeing them: drones, social media, and acoustic alerts lift the veil that once hid everyday shark behavior.

That visibility fuels the feeling of “more sharks,” even when scientists caution that detection is up faster than abundance. Think of it like switching from a dim flashlight to a stadium light – you suddenly notice what was always there, plus a bit more shaped by climate and conservation. In places where great whites have increased visits, the correlation with growing seal colonies is a central thread, not a mystery. In the Southeast, consistent winter migrations of blacktips and spinners have been documented for years, yet only recently are they widely witnessed from above. The ocean didn’t change overnight; our lens did, and the water warmed a few crucial degrees.

Why It Matters

Safety and science both stand to gain when we treat repeat shark appearances as valuable data, not just viral drama. On safety: rip currents cause far more injuries than sharks, yet a single fin can trigger beach closures that shape tourism decisions and local economies. On science: recurring sightings knit together long-term datasets that explain migration timing, nursery habitats, and ecosystem health. On policy: understanding patterns can guide where to place acoustic receivers, how to tailor advisories, and when to restrict certain fishing practices near swimmers without demonizing sharks. And on ethics: sharks are not villains; they’re apex managers of coastal food webs, keeping prey populations and behaviors in balance.

What’s different today is our ability to compare old approaches – bans, culls, blunt closures – to nimble, information-rich strategies. Instead of treating every fin as an emergency, we can calibrate risk by species, behavior, and environmental context. That means fewer blanket shutdowns and more targeted precautions at specific tide phases or bait events. It also means sharing plain-language risk tools with the public so they can make informed choices, the way weather apps empower beach planning. When we do that, fear gives way to practical awareness.

Reading the Ocean in Real Time

Across the East Coast, beaches are quietly becoming field labs, with tech and human observation working side by side. Drones relay midday snapshots of shark and bait positions, while fixed cameras watch the shifting color lines that betray where bait is packed tight. Acoustic receivers register tagged sharks approaching inlets like door chimes, and apps push those detections to managers who can adjust advisories in minutes. Lifeguards, once limited to binoculars, now coordinate with spotter pilots and researchers during peak bait runs or unusual water conditions.

For swimmers and surfers, the practical takeaways are refreshingly simple. Avoid areas with active bait balls or diving birds, give murky water a pass, and be extra conservative near jetties or steep drop-offs when the tide is pumping. Early mornings and evenings can be productive feeding windows, so pick another time if conditions look “fishy.” Fishers can help too by keeping scraps and chum away from swimmers and minding the line between recreation and shark attraction. Real-time awareness beats blanket fear, especially when the ocean is sending clear signals.

The Future Landscape

As coastal waters keep warming, expect the seasonal migration staircase to slide farther north, extending shark encounters into places that historically saw fewer. Juveniles of several species may find new nursery habitat in estuaries that cross old climate boundaries, changing where small sharks first meet the human shoreline. Offshore, artificial structures – from reefs to energy infrastructure – could alter prey maps in ways scientists are still disentangling, potentially shifting where and when sharks stage near beaches. Machine-learning detection on drones and fixed cameras will likely flag species and behavior in real time, moving advisories from broad “shark seen” alerts to more nuanced signals.

The big challenge is equity and clarity: risk messages must reach beach communities in multiple languages and formats, not just through niche apps. Long-term monitoring will need stable funding so the data do not vanish with a single grant cycle. Coastal cities will face trade-offs between tourism expectations and ecological reality during bait-heavy weeks, a negotiation best handled with transparent thresholds set before the season. And as the ocean keeps changing, cross-border data sharing from the Caribbean to Atlantic Canada will be essential to track migrations that ignore state lines. The sharks already have a plan; now it’s our turn to match it with a smarter one.

How to Share the Shore

Start by reading the water the way locals do: if birds are diving hard, bait is jittery in the troughs, and the water turns patchy, choose a spot a little farther down the beach or wait for the next tide. Swim in groups, stay close to lifeguard towers, and skip jewelry that flashes like a baitfish under a bright sun. If you fish, keep handling quick and thoughtful around sharks, and avoid leaving scent trails where families swim. Support local research groups that tag and track sharks; their data underpin the advisories that make your day safer. And when a beach closes briefly after a credible sighting, treat it less as a scare and more as a courtesy from an ocean that just rang the dinner bell.

I think back to that gray morning on the Jersey shore, watching a shadow trace the sandbar while joggers passed with coffee cups and headphones. It felt less like a horror scene and more like a reminder that we share a living border with something wild, efficient, and older than our towns. The trick isn’t to clear the ocean of sharks; it’s to clear our thinking so we can meet them with respect and good sense. If we do, the same beaches that keep seeing fins will also keep delivering safe, unforgettable days in the water. Would you have guessed the ocean’s best safety tool is simply learning to read its signals?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.