Think about the last time you held something hot. Maybe a mug filled with coffee, or your hands near a campfire. The warmth spread through your fingers gradually, didn’t it? That’s because heat typically diffuses outward from its source, dispersing slowly as energy transfers from one molecule to another. We’ve all experienced this basic thermal behavior countless times.

Here’s the thing, though. There’s an entirely different world of physics happening in exotic materials that don’t follow these conventional rules at all. In certain superfluids existing at temperatures near absolute zero, heat doesn’t spread out like you’d expect. Instead, it sloshes back and forth in waves, almost like sound bouncing around inside a container. Honestly, when you first hear about it, the concept sounds impossible.

What Makes Second Sound So Strange

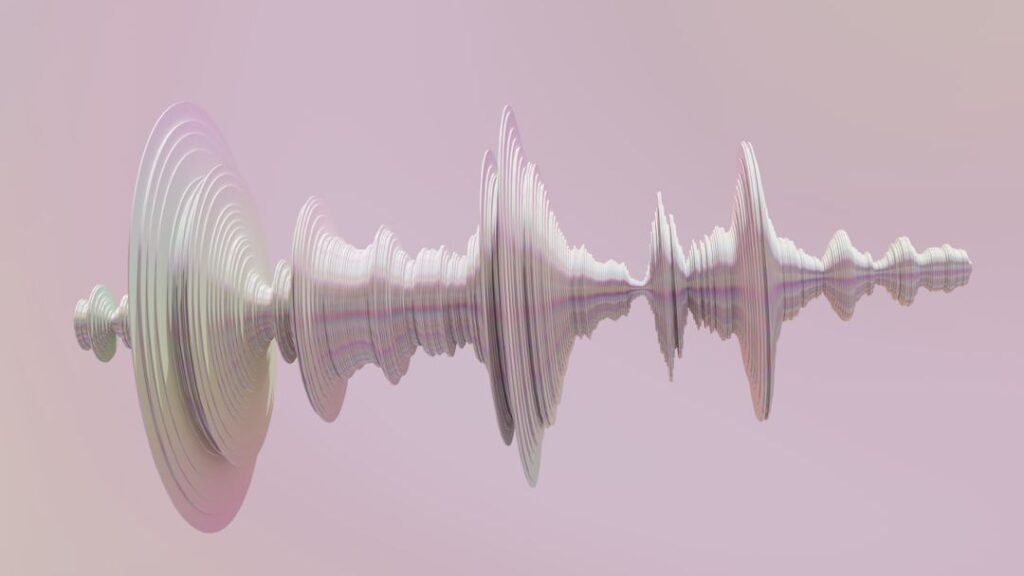

For the first time, MIT scientists have successfully imaged how heat actually travels in a wave, known as a “second sound,” through this exotic fluid. Picture this: you heat one side of a tank filled with water. Normally, the heat would slowly work its way through the liquid until everything reaches equilibrium. Instead of spreading out as one would expect, these superfluid quantum gasses “slosh” heat side to side – it essentially propagates as a wave.

The name itself tells you something important. Scientists call this behavior a material’s “second sound” (the first being ordinary sound via a density wave). In condensed matter physics, second sound is a quantum mechanical phenomenon in which heat transfer occurs by wave-like motion, rather than by the more usual mechanism of diffusion. The fluid itself might appear completely still, yet thermal energy races back and forth inside it like an invisible tide.

The Breakthrough Imaging Technique

Although this phenomenon has been observed before, it’s never been imaged. That’s what makes this recent achievement so remarkable. The challenge was enormous because there’s a big problem trying to track heat of an ultracold object – it doesn’t emit the usual infrared radiation.

MIT scientists designed a way to leverage radio frequencies to track certain subatomic particles known as “lithium-6 fermions,” which can be captured via different frequencies in relation to their temperature. Think of it like tuning a radio dial to different stations, except each frequency corresponds to a different temperature level. Warmer particles vibrate at higher frequencies, cooler ones at lower frequencies. This novel technique allowed the researchers to essentially zero in on the “hotter” frequencies (which were still very much cold) and track the resulting second wave over time.

The method required cooling a cloud of atoms to ultra-cold temperatures approaching absolute zero (−459.67 °F). At that point, something remarkable happens. The atoms lose their individual characteristics and start behaving as a collective unit, flowing without any friction whatsoever.

Why This Discovery Actually Matters

Let’s be real, most of us will never encounter a superfluid quantum gas in our daily lives. This might feel like a big “so what?” After all, when’s the last time you had a close encounter with a superfluid quantum gas? But ask a materials scientist or astronomer, and you’ll get an entirely different answer.

Understanding this dynamic could help answer questions about high-temperature superconductors and neutron stars. Superconductors are materials that can carry electrical current with almost no energy loss, which could revolutionize power transmission if we can develop versions that work at practical temperatures. Scientists are keen to study high-temperature superconductors, which carry current with little power loss. Some say that second sound might shed light on thermal transport in these systems.

Then there’s the cosmic connection. Neutron stars, those incredibly dense objects in space, may also carry clues. A quantum fluid could occupy their interiors and possibly channel heat in ways that match second sound patterns. Understanding how heat moves through these ultradense stellar remnants could unlock mysteries about their structure and behavior.

The Surprising Consistency Across Temperatures

One of the most surprising findings is that the behavior of second sound remained nearly unchanged across different temperatures. Researchers expected the friction between fluid components to vary more significantly, but the measurements showed very little temperature dependence.

This discovery challenges existing assumptions. This suggests that something else, possibly the structure of the fluid’s internal turbulence, plays a larger role than previously thought. At around 1.6 Kelvin, the second sound wave moved at approximately 15 meters per second (49 feet/s), slow compared to acoustic sound but extremely fast for thermal transport.

What’s fascinating is that these measurements contradicted what physicists expected to see. Temperature should have had a bigger impact on how the heat waves behaved, but instead, the waves maintained their character remarkably well. That hints at deeper principles governing quantum fluids that we’re only beginning to understand.

Looking Forward to New Physics

The phenomenon of second sound was first described by Lev Landau in 1941, nearly a century ago. Yet we’re only now developing the tools to truly see it in action. The journey from theoretical prediction to visual confirmation took decades of technological advancement and creative problem solving.

Scientists are now exploring how temperature pulses might drive new physics in quantum fluids and even in cosmic bodies. The applications could extend far beyond fundamental research. This clarity supports efforts to design technologies that harness quantum effects, like sensitive sensors or more efficient cooling systems.

I think the most exciting part is realizing how much we still don’t know. Every time we develop a new way to observe nature at these extreme conditions, we discover behaviors that challenge our understanding of physics. Second sound reminds us that heat, something we experience every single day, still has secrets to reveal when pushed to the absolute limits of temperature and quantum behavior.

The fact that MIT researchers can now watch pure heat sloshing back and forth like water in a bucket represents more than just a technical achievement. It’s a window into a realm of physics where our everyday intuitions completely break down, and nature reveals behaviors that seem almost magical. What other phenomena are waiting to be visualized once we develop the right tools to see them?

Hi, I’m Andrew, and I come from India. Experienced content specialist with a passion for writing. My forte includes health and wellness, Travel, Animals, and Nature. A nature nomad, I am obsessed with mountains and love high-altitude trekking. I have been on several Himalayan treks in India including the Everest Base Camp in Nepal, a profound experience.