You’ve probably wondered about it at some point, lying awake at night staring at the ceiling. Where did we come from? Not just humans, but the very essence of life itself. It’s wild to think that billions of years ago, our planet was a barren, hostile rock, yet somehow, from that chaos, the first spark of life ignited. That ancient mystery has puzzled scientists for generations. The good news? We’re getting closer to cracking it. Recent discoveries are offering us the most detailed picture yet of how life might have first emerged on our planet, and some of these findings are genuinely surprising.

The pieces of this puzzle are finally starting to fit together. From deep beneath the ocean’s surface to the shores of ancient lakes, from microscopic droplets to complex cellular machinery, researchers are uncovering clues that paint a vivid portrait of Earth’s primordial past. These aren’t just abstract theories anymore. Scientists are actually recreating the conditions of early Earth in laboratories and watching chemistry transform into something that looks remarkably lifelike. Let’s dive into what they’ve discovered.

Complex Life Started Much Earlier Than We Thought

Here’s something that’ll make you rethink everything. New research published in Nature reveals that the transition to complex life began nearly 2.9 billion years ago, almost a billion years earlier than previously estimated. Think about that for a moment. A billion years is an incomprehensible stretch of time, yet we were off by that much in our understanding.

What’s even more startling is that complex organisms evolved long before substantial levels of oxygen existed in the atmosphere, contradicting the long-held belief that oxygen was a prerequisite for complex life. Scientists used an expanded molecular clock approach, analyzing over a hundred gene families to piece together this timeline. The team has proposed a new scenario called CALM, which stands for Complex Archaeon, Late Mitochondrion, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of cellular evolution.

The Primordial Soup Gets a Modern Makeover

You’ve probably heard of the primordial soup, that murky mixture of chemicals where life supposedly began. It sounds almost mythical, doesn’t it? Yet this concept, first proposed by Alexander Oparin in 1924 and J.B.S. Haldane in 1929, has been getting some serious updates lately.

Recent research published in Science Advances suggests that microlightning in water droplets could have sparked the creation of Earth’s earliest organic molecules. Picture ancient Earth with its violent storms and churning seas. Instead of relying solely on dramatic lightning strikes, which were likely too infrequent, tiny electrical discharges between charged water droplets in mist could have constantly produced amino acids in pools and puddles. This process would have been far more common than traditional lightning, creating a steady supply of life’s building blocks. It’s like having millions of tiny molecular factories operating continuously rather than waiting for occasional lightning bolts.

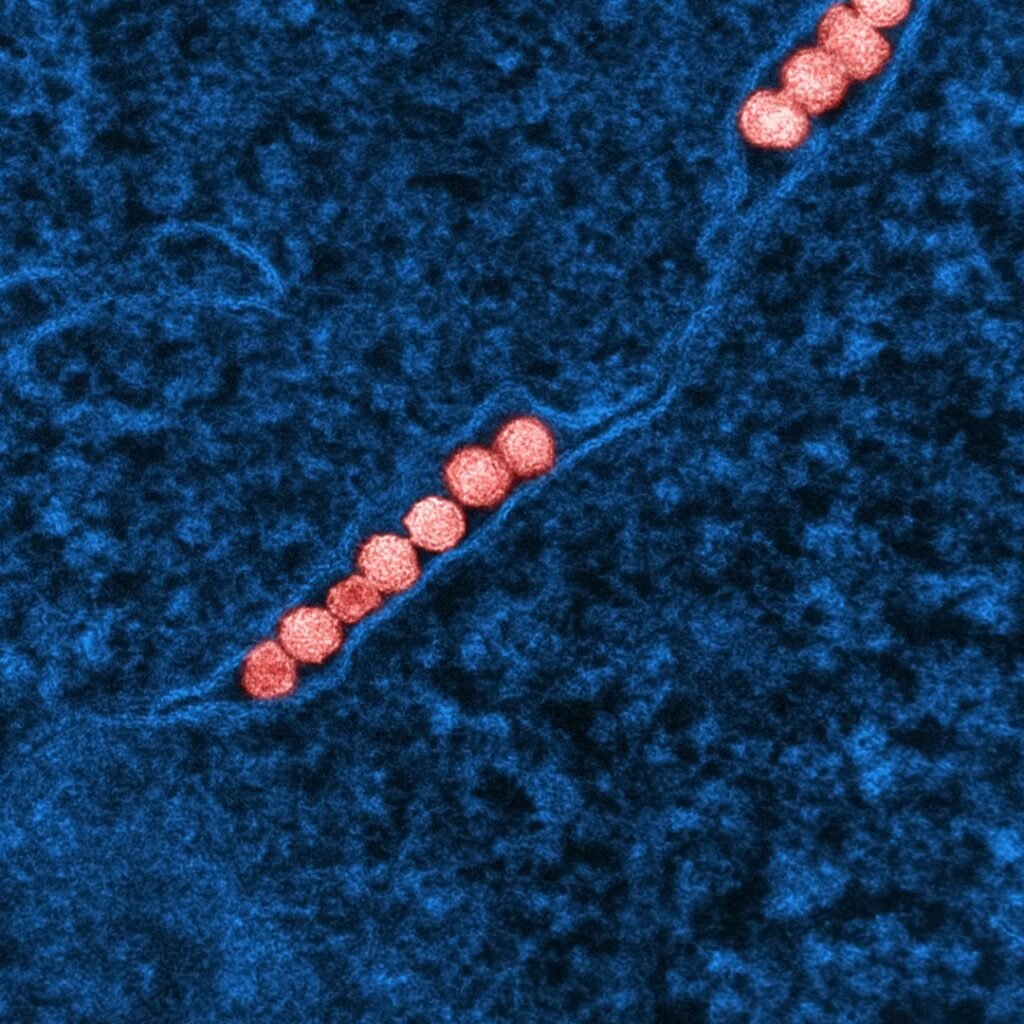

Hydrothermal Vents as Life’s Birthplace

Imagine descending to the ocean floor where crushing pressure and scalding heat meet in complete darkness. There are two main types of hydrothermal vents: the hot black smoker type at approximately 350 degrees Celsius, driven by magma chambers, and the cooler Lost City type at roughly 50 to 90 degrees Celsius, driven by a process called serpentinization. These alien-looking chimney structures might actually be where life first took hold.

By creating protocells in hot, alkaline seawater, a UCL-led research team has added evidence that the origin of life could have occurred in deep-sea hydrothermal vents rather than shallow pools. What makes these vents so special? The driving force behind metabolic energy release ultimately traces to a steady geochemical interface of hydrogen and carbon dioxide, a chemical mixture brimming with energy like a fresh battery. The chemistry happening at these vents closely mirrors the core metabolic reactions found in ancient single-celled organisms, providing a compelling link between geology and biology.

RNA World Before DNA Took Over

Before DNA became the master blueprint for life, there was likely a simpler system. Researchers think that life descends from an RNA world, although other self-replicating molecules may have preceded RNA. RNA is fascinating because it can do two jobs at once: store genetic information like DNA and catalyze chemical reactions like proteins.

In 2022, a team in the United States generated stable RNA strands in the laboratory by passing nucleotides through volcanic glass, creating strands long enough to store and transfer information. This is huge because volcanic glass was present on early Earth thanks to frequent meteorite impacts and high volcanic activity, and the nucleotides used are believed to have been present at that time. The experiments are starting to show plausible pathways from simple chemistry to self-replicating molecules, bridging that mysterious gap between lifeless matter and living systems.

Harvard Scientists Create Artificial Cells That Behave Like Life

This is where things get really exciting. A Harvard team has created artificial cell-like chemical systems that simulate metabolism, reproduction, and evolution, generating structures with properties of life from completely homogeneous chemicals devoid of any similarity to natural life. It sounds like science fiction, yet it’s happening in laboratories right now.

The vesicles they created ejected more components like spores, and these expelled structures slightly differed from each other, with some proving more likely to survive and reproduce, modeling what researchers called a mechanism of loose heritable variation. That’s essentially Darwinian evolution in a test tube. The implications are staggering. If scientists can create lifelike systems from scratch, it suggests that the jump from chemistry to biology might not be as impossibly difficult as we once imagined.

Japanese Researchers Find Self-Reproducing Droplets

Meanwhile, researchers in Japan have been working with coacervate droplets, tiny clusters of molecules that act like primitive cells. Unlike viruses and molecular replicators, these droplets demonstrate self-reproduction, a defining feature of life, and highlight the importance of periodic environmental stimuli in enabling recursive proliferation.

One study suggests that coacervate droplets could represent a critical evolutionary step, bridging the gap between molecular assemblies and life. These aren’t fully alive in the way we typically understand life, yet they’re not just inert chemicals either. They exist in that fascinating gray zone where chemistry starts behaving in ways that remind us of biology. Such findings challenge the long-standing RNA world hypothesis, which posits that life originated from self-replicating RNA molecules, suggesting there might be multiple pathways to life’s emergence.

The Building Blocks Arrived From Space

Here’s something that might blow your mind. You’re partially made of stardust, and that’s not poetic exaggeration. In 1969, the Murchison meteorite that fell in Australia contained dozens of different amino acids, the building blocks of life. We’ve even found these crucial molecules on asteroid samples retrieved directly from space.

Research showed that complex organic compounds were readily produced under conditions likely present in the early solar system when many meteorites formed, suggesting meteorites might have served as cosmic transporters of molecular seeds to Earth. Think of it as the universe delivering care packages to our young planet. Missions like Hayabusa and OSIRIS-REx are bringing us pieces of asteroids, helping us understand the conditions that form planets, and scientists are optimistic that these findings will lead to huge progress in answering the origin question.

Proteins and RNA Might Have Co-Evolved Together

One of the biggest puzzles has always been the chicken-and-egg problem: which came first, proteins or nucleic acids? Modern cells need both, yet each requires the other to function. In a study published in Nature, a team demonstrated how RNA molecules and amino acids could combine through purely random interactions to form proteins, the essential molecules carrying out nearly all cellular functions.

Researchers focused on a reactive molecule called pantetheine, which is crucial for metabolism, and found that when mixed with amino acids, they created aminoacyl-thiol, which then combined with free-floating RNA in water to transfer amino acids to the RNA. It’s not a perfect system yet. The amino acid chains being produced are still random and chaotic, unlike the orderly arrangements in living cells. However, give these chemicals billions of years to interact, and the possibilities become endless.

Ancient Earth’s Oceans Hid the Secret Rise of Complexity

Complex life began taking shape in Earth’s oxygen-free oceans nearly a billion years earlier than previously believed. Let that sink in. The narrative we’ve been told about life requiring oxygen to evolve complexity turns out to be incomplete at best.

The archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes began evolving complex features roughly a billion years before oxygen became abundant, in oceans that were entirely anoxic, with crucial cellular features emerging in these ancient oxygen-free environments. The evidence suggests that structures such as the nucleus emerged well before mitochondria, completely flipping the script on how we thought complex cells assembled themselves. The process of cumulative complexification took place over a much longer time period than previously thought, indicating that evolution works on timescales we’re only beginning to appreciate.

What This All Means for Our Understanding

So where does all this leave us? We’re standing at an extraordinary moment in scientific history. The question of how life began is no longer purely philosophical. It’s becoming an experimentally testable problem with tangible, reproducible results. Scientists aren’t just theorizing anymore. They’re recreating the conditions of early Earth and watching chemistry cross that mysterious threshold into something resembling life.

What strikes me most is how many different pathways to life seem plausible. Maybe it wasn’t one lucky accident in one special place. Perhaps life emerged multiple times in multiple locations, from hydrothermal vents to sunlit pools to mineral surfaces. The universe might be far more fertile for life than we imagined. These discoveries also have profound implications beyond Earth. If life can start in oxygen-free oceans, beneath crushing pressures, or from droplets in mist, then the moons of Jupiter and Saturn with their subsurface oceans suddenly become much more interesting targets in our search for life elsewhere.

We’re not just learning about the past. We’re gaining insights that could guide us toward discovering whether we’re alone in the cosmos. Every experiment bringing us closer to understanding life’s origins also brings us closer to answering that ultimate question: are we unique, or is life an inevitable consequence of chemistry and time? What do you think about it? Does knowing we came from such humble chemical beginnings change how you see yourself and the world around you?