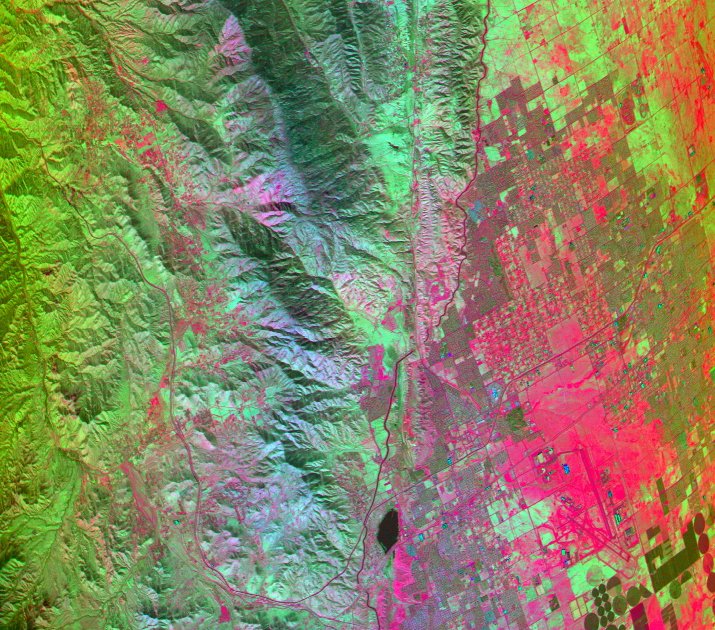

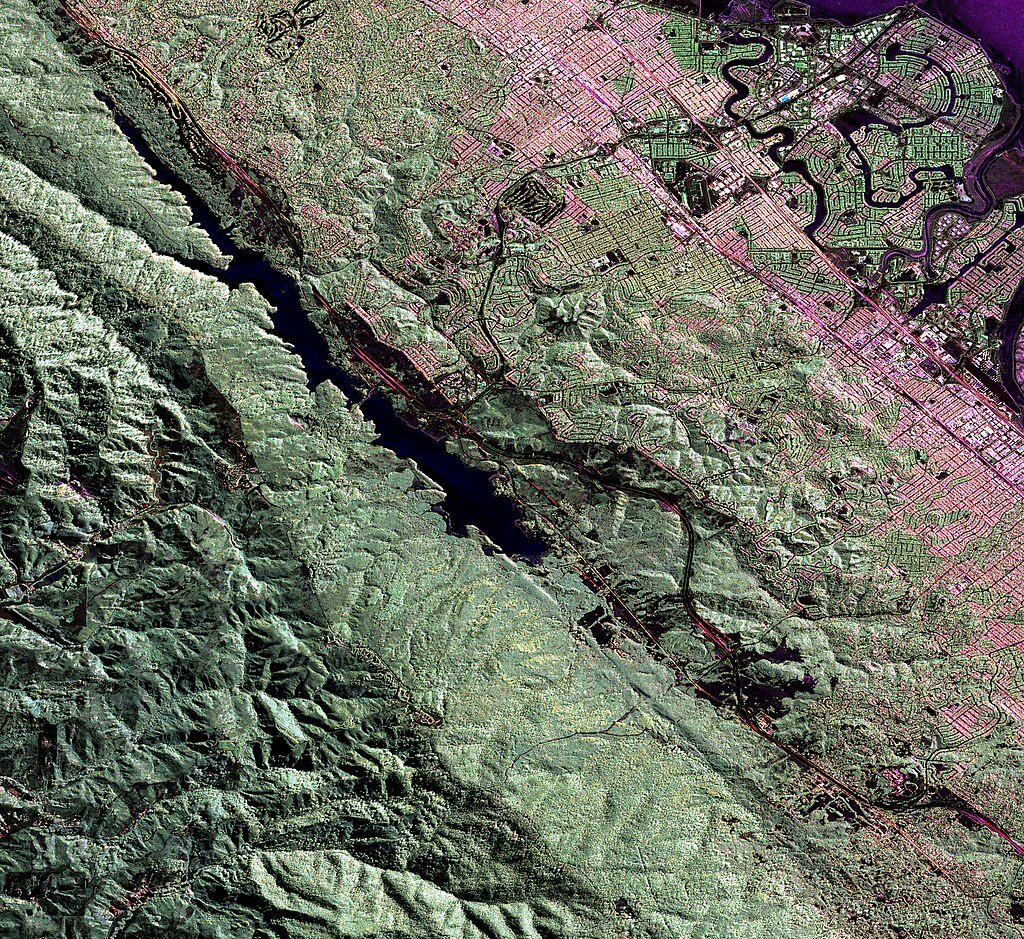

The San Andreas Fault isn’t just a crack in California’s crust; it’s a bomb that is going off. This tectonic boundary between the Pacific and North American plates runs for more than 800 miles (1,300 km) from the Salton Sea to Cape Mendocino. It has changed the shape of California’s land and its future in earthquakes. The fault is a study in geological tension, from the terrible 1906 San Francisco earthquake to the strange quiet of its “creeping” central section. Scientists say that the next “Big One” is not a matter of if, but when. It could have effects that change cities, economies, and millions of lives. Find out what makes the San Andreas so dangerous, how it formed, and why California’s future depends on its movements.

A Fault Born From a Tectonic Collision

There was a time when the San Andreas Fault didn’t exist. The Farallon Plate was moving under North America about 30 million years ago, but things changed when the Pacific Plate started to move in. The Pacific Plate didn’t go down, instead, it started to slide sideways, forming the transform boundary we know today. This change caused the San Andreas to form. It now moves 1.3 to 1.5 inches (33–37 mm) per year, bringing Los Angeles closer to San Francisco by geologic inches each year.

If this keeps up, LA and San Francisco will be next to each other in 15 million years, a slow-motion crash written in stone.

The Three Faces of the San Andreas

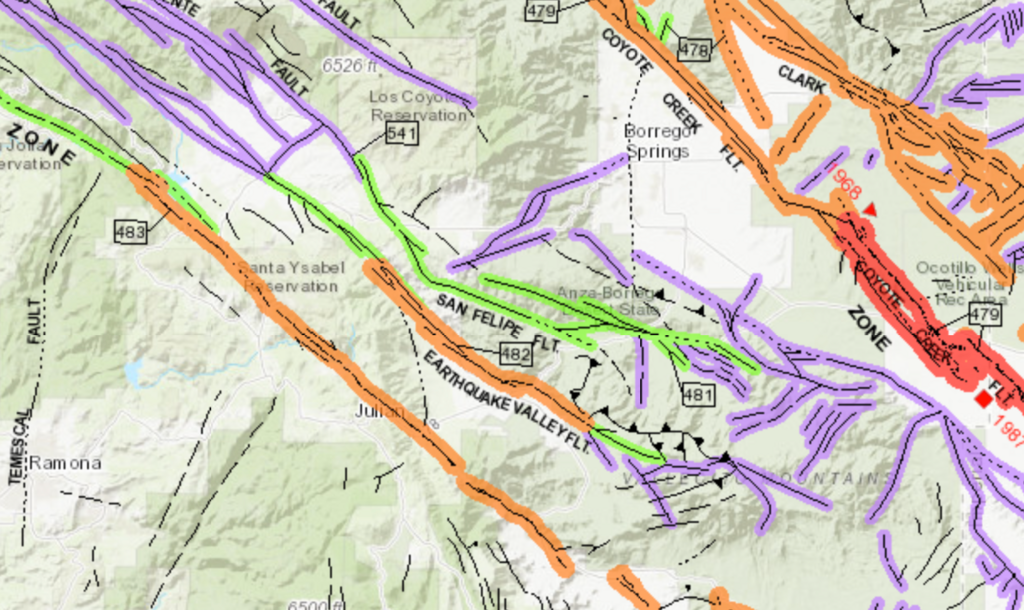

The fault isn’t the same all the way through; it’s split into three parts, each with its own personality:

- Southern Segment (Bombay Beach to Parkfield): The most dangerous. The last time this area broke was in 1857, when a 7.9-magnitude earthquake hit Fort Tejon. It’s late now, and there’s a 19% chance of a 6.7+ quake near Los Angeles by 2043.

- Central Segment (Parkfield to Hollister): The area where things are “creeping.” The fault here moves smoothly, which keeps big earthquakes from happening, but scientists think that big earthquakes may have happened in the past.

- The Northern Segment, which runs from Hollister to Mendocino, was the site of the 1906 disaster. This part has a 22% chance of a 6.7 or higher quake by 2043, but its deeper locking mechanism could cause an even worse rupture.

The 1906 Quake: A Preview of Catastrophe

A 7.9-magnitude earthquake hit San Francisco on April 18, 1906, at 5:12 AM. It broke 296 miles (477 km) of the fault. The shaking lasted 45 to 60 seconds, but the fires that followed burned for three days, killing more than 3,000 people and leaving 225,000 homeless, which is more than half of the city’s population.

The quake moved fences and roads by 21 feet (6.4 meters) in some places, which was a very real reminder of how strong the fault is.

The “Big One” Scenario: What Could Happen?

A 7.8-magnitude earthquake on the southern San Andreas could be the “Big One” that

- More than 1,800 people will die and 50,000 will be hurt.

- Cause $200 billion in damage, bringing down old buildings and cutting off water lines.

- Set off simultaneous breaks on nearby faults like San Jacinto or Hayward, making the damage worse.

If both the Cascadia Subduction Zone and the San Andreas rupture, it could make disasters worse.

Can We Predict the Next Earthquake?

Short answer: No, there’s no set date. However, the odds aren’t in our favor:

- There’s a 72% chance of a 6.7 magnitude or greater earthquake hitting the Bay Area by 2043.

- For Southern California, that likelihood jumps to 93% in the same time frame.

As for the “overdue” myth: While the 1857 earthquake in Southern California suggests a 100-150-year cycle, faults don’t work on a timeline. Stress might release tomorrow, or it could take decades.

Living on the Fault: Oases, Hikes, and Hidden Risks

The San Andreas doesn’t just destroy things; it also makes strange landscapes:

- The fault’s cracks let groundwater rise to the surface, which feeds palm groves like Thousand Palms Oasis in the Coachella Valley.

- Carrizo Plain: A clear, sharp scar where the fault’s lateral shift is most obvious.

- Urban Dangers: The fault runs under San Bernardino, Palmdale, and even a BART tunnel that was built on top of a sleeping giant.

Preparing for the Inevitable

Retrofitting is the key to California’s survival:

- Older buildings (built before 1980) are the most at risk because they are often not bolted to their foundations.

- “Drop, Cover, Hold On” is still the best way to stay alive.

The San Andreas is more than just a fault, it’s a sign that the ground below us is alive. And one day, it will wake up.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.