Have you ever gazed at a woven basket, a painted rock, or a beaded garment and felt a strange sense of harmony—like the shapes themselves were trying to tell you something? Across continents and centuries, Indigenous artists have harnessed the power of sacred geometry to create art that doesn’t just please the eye, but weaves together stories, landscapes, and spiritual beliefs. These patterns aren’t just decoration; they are maps of memory, blueprints of belonging, and silent storytellers that bridge the human and natural worlds. Unraveling the mysteries of these geometric designs, we find a stunning tapestry of science, art, and spirit—one that invites us to look closer, and perhaps see the world, and ourselves, in a new light.

The Universal Appeal of Geometric Patterns

Geometric patterns have a magnetic allure that transcends culture and time. From the spirals of ancient petroglyphs to the interlocking triangles of intricate beadwork, these shapes seem to speak a universal language. Psychologists suggest that humans are naturally drawn to symmetry and repetition because our brains are wired to seek order in chaos, making geometric art instantly captivating. Indigenous artists, however, take this a step further, infusing these forms with layers of meaning that connect the individual to the cosmos. Whether it’s a circle representing the cycle of life or a labyrinthine pattern symbolizing a spiritual journey, every shape serves a purpose. The repetition of these motifs also brings a sense of continuity across generations, making geometric art a living tradition that never loses its relevance.

Ancient Roots: Geometry in Rock Art and Petroglyphs

Long before written language, Indigenous peoples across the world were etching, painting, and carving geometric shapes into stone. These ancient artworks, found on rocks and cave walls from Australia to the Americas, are more than decorative. Spirals, zigzags, and concentric circles often represent water sources, star paths, or sacred sites. Scientists studying these petroglyphs have found that many align with astronomical events—evidence that geometry was used as a tool for understanding the universe. The act of creating these designs was often ceremonial, linking the artist and their community to the land itself. These early examples show that sacred geometry is not just an artistic choice, but a profound way of seeing and marking the world.

The Circle: Symbol of Unity and Cycles

Few shapes are as evocative as the circle, a symbol that appears again and again in Indigenous art. For many cultures, the circle embodies unity, wholeness, and the endless cycle of life, death, and rebirth. In Native American medicine wheels, the circle represents the interconnectedness of all beings and the four directions. Australian Aboriginal dot paintings often use circular motifs to map out waterholes or gathering places, turning geometry into a visual map of country. The circle’s perfection—no beginning, no end—mirrors the natural rhythms of the earth and sky, making it a powerful emblem of continuity and belonging. Its simplicity belies a deep spiritual resonance that continues to inspire artists and storytellers alike.

Spirals and Labyrinths: Pathways of Transformation

Spirals pull the eye inward, inviting contemplation and wonder. In Indigenous art, spirals often symbolize journeys—both physical and spiritual. Maori artists in New Zealand carve koru (spiral) designs into wood and bone, representing growth, new beginnings, and the unfurling of the fern. In the American Southwest, Ancestral Puebloan petroglyphs feature spirals that may map out migratory routes or solar cycles. The spiral’s endless curve becomes a metaphor for personal and communal transformation, where each turn brings new insight. Labyrinthine patterns, likewise, tell stories of pilgrimage and self-discovery, blurring the lines between map, memory, and myth.

Triangles and Diamonds: Markers of Identity and Movement

Triangles and diamonds are more than just eye-catching shapes—they are powerful symbols of identity and movement in Indigenous art. Many African and Native American textiles feature repeated diamond patterns, each one signifying a particular tribe, family, or social role. In the Andes, Inca weavers used stepped triangles to represent mountains and rivers, the very bones of their homeland. These shapes often serve as visual shorthand for journeys taken, battles fought, or ancestors honored. The sharp lines and points evoke direction and dynamism, reminding viewers that life itself is always in motion, shaped by both tradition and change.

Symmetry and Balance: Harmonizing Art and Nature

Symmetry is everywhere in nature, from the wings of butterflies to the branches of trees. Indigenous artists often mirror this natural balance in their work, creating designs that reflect the order of the world around them. The use of bilateral or radial symmetry in patterns shows a deep understanding of ecological relationships. For instance, Inuit artists carve symmetrical motifs that echo snowflakes and animal tracks, highlighting their connection to the Arctic environment. This harmony between art and nature is more than aesthetic; it’s a philosophy of respect and reciprocity, an acknowledgment that humans are just one part of a much larger pattern.

Mathematics in the Hands of the Ancestors

It’s easy to forget that geometry is, at its core, a branch of mathematics. Many Indigenous artists were—and are—sophisticated mathematicians, able to visualize complex patterns and ratios without formal schooling. The process of creating intricate beadwork or weaving often involves calculations of angles, symmetry, and proportion. Recent scientific studies have marveled at the mathematical precision in Navajo rugs or Zulu basketry, revealing knowledge systems that rival those of ancient Greece or Egypt. This blending of mathematics and art is not just impressive; it’s a testament to the intellectual legacy carried forward by Indigenous communities.

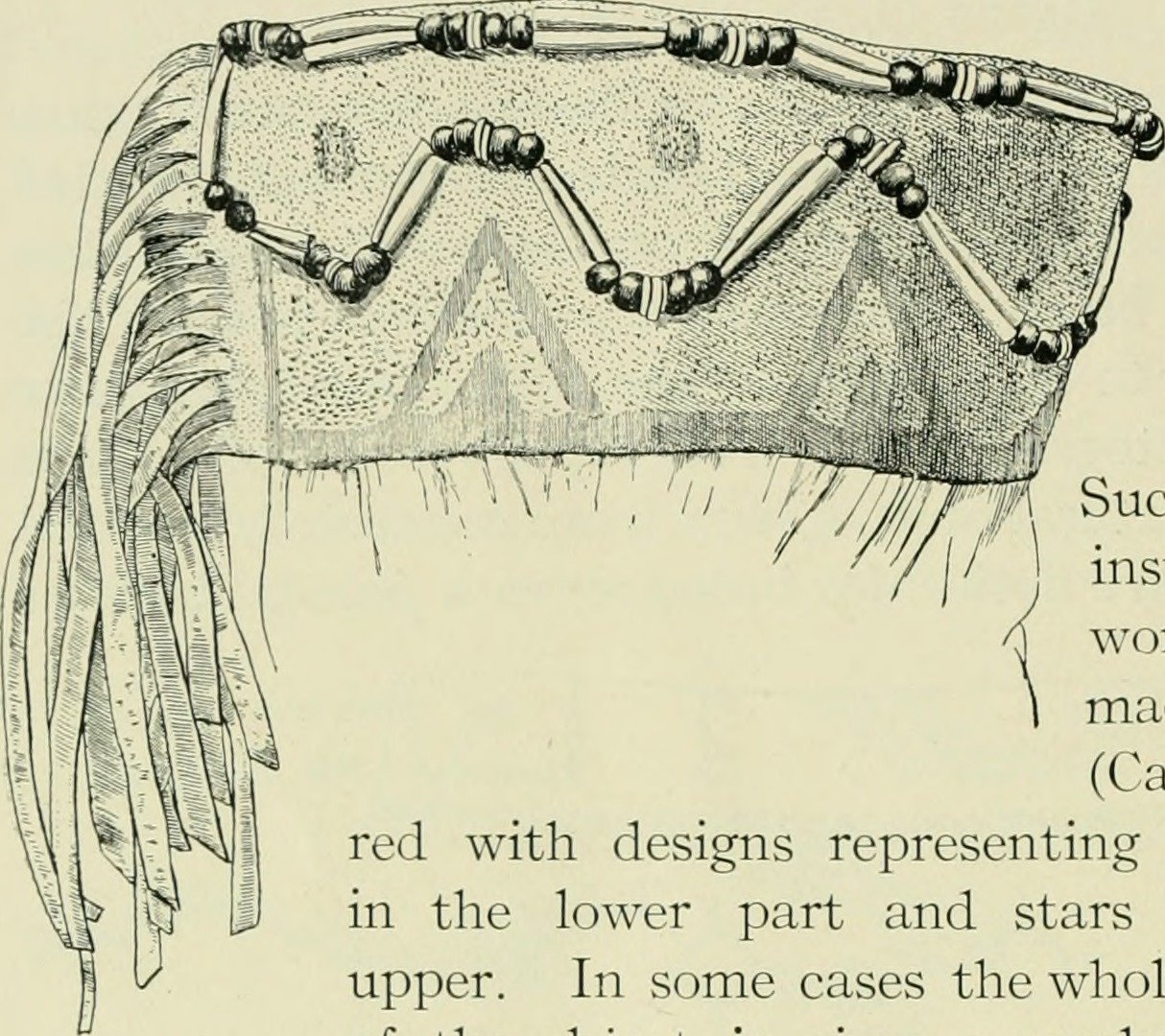

Mapping Place and Story Through Pattern

For Indigenous peoples, art is inseparable from place. Geometric patterns often serve as visual maps, encoding stories and histories that are tied to specific landscapes. In Australia, Aboriginal artists use mosaics of dots and lines to record Dreamtime journeys and sacred sites—maps that can only be fully understood by those initiated in their meanings. In North America, quillwork and beadwork tell stories of migration, survival, and adaptation, using motifs that change as families move across the land. This visual language turns every garment, basket, or carving into a living archive, preserving the memory of place for future generations.

Color and Geometry: Emotions in Every Hue

The impact of sacred geometry in Indigenous art is heightened by the careful use of color. Each hue carries its own symbolism—red for earth, blue for water, yellow for the sun, black for night. The interplay of color and shape can evoke emotions, signal clan affiliations, or mark the passage of seasons. In the art of the Plains tribes, for example, certain geometric designs are paired with specific colors to invoke protection or healing. This emotional resonance transforms geometric art into an experience that is both visual and visceral, drawing viewers into a world where every line and shade has a purpose.

Geometry as a Living Tradition

Sacred geometry in Indigenous art is not a relic of the past; it continues to evolve in the hands of contemporary artists. Today, painters, sculptors, and digital creators reinterpret traditional motifs in new and exciting ways, blending old wisdom with modern innovation. These artists use geometry to speak out about identity, resilience, and environmental stewardship. They remind us that sacred shapes are not just about the past, but about carving out a place in the present and the future. The language of geometry remains alive, ever-changing, and always deeply meaningful.

Science and Spirit: Bridging Worlds Through Art

At its heart, sacred geometry in Indigenous art is a bridge between worlds—the scientific and the spiritual, the personal and the communal, the seen and the unseen. By studying these patterns, scientists gain insights into ancient knowledge of astronomy, ecology, and mathematics. Meanwhile, the spiritual dimensions of these shapes remind us that art is also about connection, reverence, and belonging. The beauty of sacred geometry lies in its ability to hold many truths at once, inviting us to see with both the mind and the heart. As we trace the lines and curves crafted by Indigenous hands, we are invited to listen—to the land, to the ancestors, and to the stories written in shape and color.