Behind the colorful battles and catchy theme music lies a quiet biological truth: many beloved Pokémon carry the fingerprints of real wildlife. Natural history – spanning venom tricks, fossil forms, and migration stories – has quietly shaped characters that feel familiar even when they breathe fire. Scientists and designers alike have long mined the same library of life, turning field notes into cultural icons. Understanding those roots doesn’t just satisfy curiosity; it opens a door to seeing nature with fresh attention. And in 2025, with biodiversity under pressure, that attention matters more than ever.

The Hidden Clues

Start with the subtle details, because that’s where the magic often hides: Caterpie’s bright, forked “horn” mirrors the osmeterium of swallowtail caterpillars, a fleshy organ they pop out to startle predators with sharp scents. Poliwag’s belly spiral nods to the visible gut coil in translucent tadpoles, a small reality inflated into a memorable motif. Pikachu, meanwhile, borrows its cheeky charisma from small mammals with food-storing cheek pouches; its original design famously leaned squirrel rather than mouse, which explains the rounded face and springy posture. Sandshrew and Sandslash evoke pangolins and armadillos, masters of armor who curl into near-spherical shields when threatened. Even Wooper winks at the axolotl, a salamander that keeps gills into adulthood, a real-life lesson in arrested development known as neoteny. These aren’t random flourishes; they’re field-guide notes translated into pop culture.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

The pipeline from nature to character sheet looks surprisingly like the scientific process: observe, sketch, compare, refine. Early concept artists leaned on the same references biologists use – field guides, museum halls, and preserved specimens that display anatomy without motion blur. Today, high-resolution wildlife photography, CT scans of museum fossils, and slow-motion videos of animal movement offer an archive richer than anything available when the first games launched. Designers can freeze a cormorant plunging after a fish or zoom into the crown of spines on a venomous starfish, then amplify what looks most distinctive. I once compared a museum pangolin specimen to a Sandslash figure on my desk and realized the silhouette – the arched back, the layered scales – does most of the storytelling. The result is creature design that feels grounded even when it’s fantastical.

Fossils, Birds, and Monsters in the Mind

Prehistoric life supplied a deep well of inspiration, with pterosaurs and plesiosaurs informing the aerodynamic menace of Aerodactyl and the serene, long-necked grace that echoes in Lapras. Fossil-based lines like Tyrunt and Tyrantrum lean into tyrannosaur hallmarks – robust skulls, heavy tails, and a posture built for power – while keeping proportions approachable. Birds add another thread: owls and corvids shape the bearing of modern avian Pokémon, from silent, precision hunters to glossy, steel-blue sentinels. That resonance works because birds really are living dinosaurs, carrying forward traits like hollow bones and high metabolic engines into modern skies. When players say a design “feels real,” they’re responding to evolutionary memory written into wings, beaks, and stance. It’s less fantasy, more remix of deep time.

Fire, Venom, and Mimicry

Nature’s defense playbook has always been irresistible to designers because it’s already dramatic. Arbok’s hood traces to real cobras that flare ribs to look larger, while Seviper echoes the bold striping and head shape of venomous vipers. Toxapex, bristling with spikes, channels the crown-of-thorns starfish, a reef predator whose spines can deliver painful stings and whose outbreaks reshape coral communities. Kecleon carries the chameleon idea forward, blending the notion of color-shift camouflage with a radar line down its belly that reads like a stylized lateral line. Even coloration strategies – aposematism in poison dart frogs or coral snakes – slip into palettes that warn, taunt, or deceive, then get stylized for readability on a tiny screen. Mimicry and toxins aren’t just plot devices; they’re nature’s field-tested survival tech.

Oceans as a Design Lab

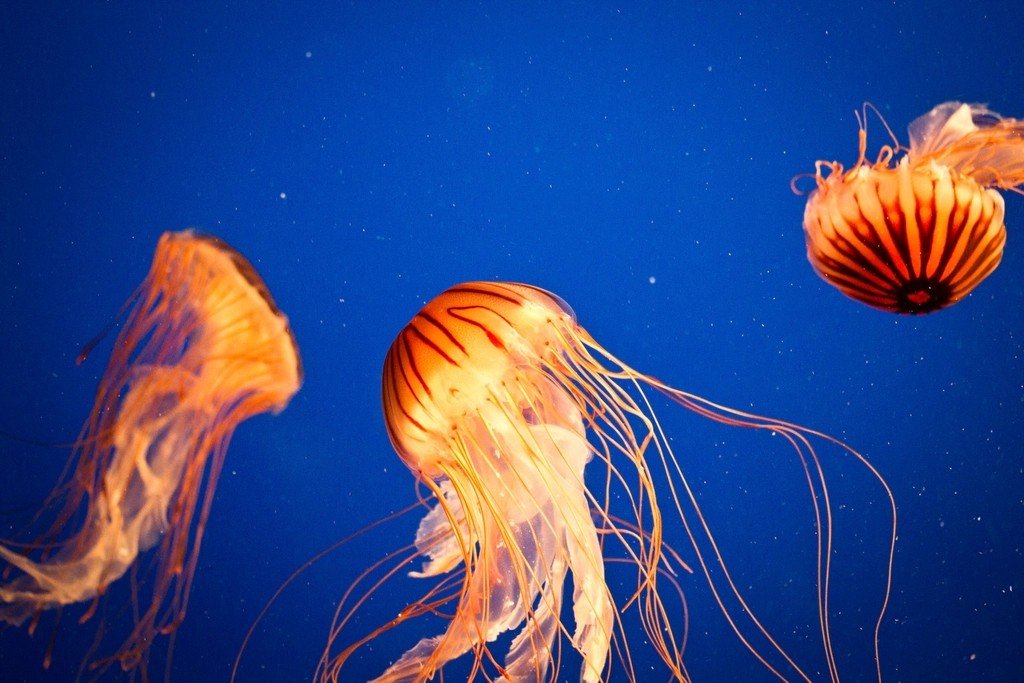

The sea is where form gets strange, which is perfect for creature design that needs to surprise without breaking biology. Cramorant wears the cormorant’s fishing lifestyle openly, showcasing a throat and beak built for slippery prey, while Sharpedo condenses shark hydrodynamics into a compact torpedo. Shellos and Gastrodon take a page from nudibranchs – sea slugs whose waving cerata and neon colors signal toxicity – and turn soft-bodied elegance into approachable charm. Dewgong signals its dugong lineage right in the name, fusing sirenian heft with seal-like motion, a reminder that common names often muddle real evolutionary branches. Wishiwashi exaggerates schooling behavior into a literal swarm-entity, but the core insight holds: small fish survive by synchronizing into something big. The ocean’s lesson is clear – change the medium and new shapes emerge.

Why It Matters

Designs rooted in real animals do more than look cool; they act as on-ramps to science literacy. When a child learns that Caterpie’s “antenna” mimics an osmeterium or that Wooper resembles an axolotl that never grows up, words like gland, neoteny, and aposematism stop feeling intimidating. Compared with traditional textbook routes, games reverse the order: curiosity comes first, terminology follows naturally. That pattern is gold for public engagement, especially when biodiversity is declining and attention is scarce. Tying a character to a conservation story – pangolins threatened by trafficking, axolotls by habitat loss – turns fandom into empathy without scolding. The broader scientific importance is simple: familiarity breeds care, and care fuels better decisions about the living world.

The Future Landscape

Creature design is entering a new phase where biology and technology will mingle even more tightly. High-speed 3D capture of animals in the wild, museum-grade CT scans of fossils, and motion-analysis datasets can feed designers details once invisible to the naked eye. That fidelity could bring new families of organisms into the spotlight – think velvet worms, mantis shrimps, or gliding lizards – without distorting what makes them special. The challenge will be ethical as much as technical: honoring cultural stories tied to animals, avoiding harmful stereotypes, and staying sensitive to species under pressure from trade or habitat loss. There’s also a global equity angle, since biodiversity – and thus design inspiration – is unevenly mapped across regions. If studios partner with researchers and local communities, the next generation of creatures could double as ambassadors for real ecosystems.

Conclusion

You don’t need a lab coat to join this conversation; you just need to notice more. Visit a natural history museum and compare silhouettes – you’ll spot the pangolin in Sandslash and the cormorant in Cramorant faster than you expect. Try a local bioblitz or a backyard survey using a field guide; matching a real nudibranch to Gastrodon is both delightful and eye-opening. Support conservation groups protecting pangolins, axolotls, dugongs, and coral reefs, the very species that gave our favorite characters their spark. Encourage schools and libraries to stock modern field guides and museum passes so curiosity has somewhere to go. When entertainment and ecology shake hands, everybody wins.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.