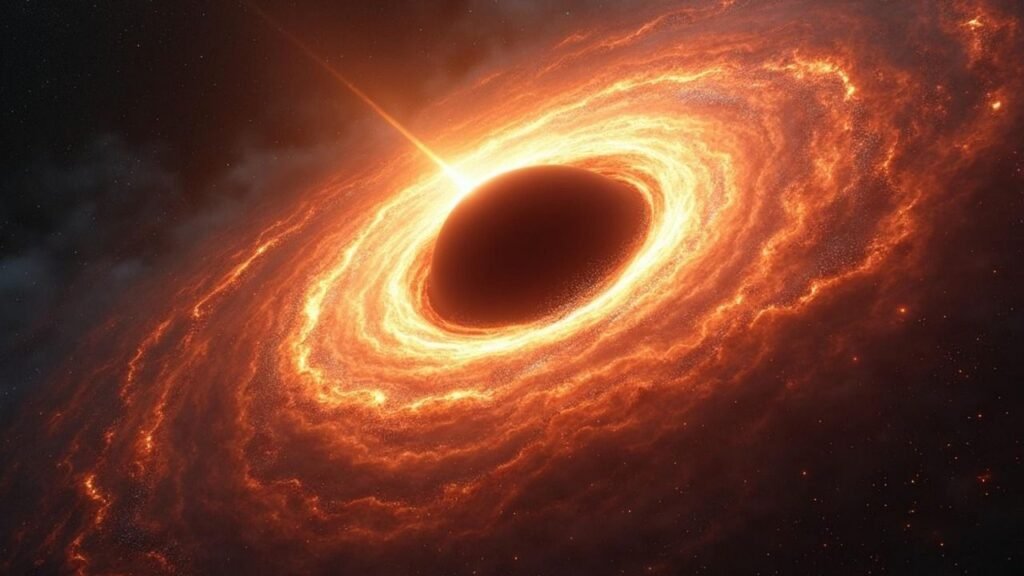

Picture this: for more than two decades, modern cosmology has treated dark energy like an invisible cosmic engine, silently pushing galaxies apart. We cannot see it, cannot touch it, but we have been told it makes up most of the universe. Now imagine being told that maybe this mysterious force is not needed at all – that the expansion of the universe could be driven instead by something we already know exists: singularities, the extreme regions surrounding black holes and other ultra-dense objects.

In recent years, a small but vocal group of physicists has begun challenging the reigning dark energy story, suggesting that what we interpret as a smooth, accelerating expansion might actually be the large-scale effect of highly uneven, singularity-dominated regions of spacetime. It is a bit like realizing the “average” depth of an ocean is misleading because of the trenches at the bottom. In this article, we will walk through what this bold claim really means, why singularities might be more important than the cosmic “average,” and how this debate could reshape our understanding of the entire cosmos.

The Standard Story: Dark Energy as the Cosmic Engine

For most cosmologists today, the universe is guided by a surprisingly simple recipe: a little bit of ordinary matter, a lot of dark matter, and a dominant ingredient called dark energy. This picture, often called the standard cosmological model, emerged in the late nineteen-nineties when observations of distant supernovae suggested that cosmic expansion is not just continuing but actually speeding up. To explain that acceleration, physicists added a new term to Einstein’s equations, often described as a cosmological constant or a smooth, repulsive energy permeating empty space.

In that framework, dark energy acts like an invisible pressure that pushes galaxies away from one another over vast scales, overpowering the pull of gravity at very large distances. The math works impressively well: dark energy helps explain supernova data, the pattern of temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, and the distribution of galaxies on the largest scales. Still, there is a huge problem: we do not know what dark energy actually is, and attempts to connect it to known physics run into wild discrepancies, sometimes off by factors so large they sound almost comical. That enormous disconnect has kept the door open for rival explanations.

Enter the Rebels: Singularities and Cosmic Inhomogeneity

Some physicists argue that the standard model of cosmology makes a dangerously convenient assumption: that on large scales the universe is smooth, homogeneous, and can be described like a calm, evenly expanding balloon. But when you zoom in, spacetime is full of violent structures: black holes, galactic clusters, and ultra-dense regions with extreme gravity, all of which are anchored by singularities or near-singular gravitational fields. These are not just minor wrinkles; they are like deep wells carved into the fabric of spacetime itself.

The rebel view suggests that these deep gravitational wells could, when properly averaged, change the way the universe expands without needing a new form of energy. Instead of treating the cosmos like a perfectly smooth soup, this approach insists on respecting the lumps and spikes, especially the singular regions where density and curvature soar. In this perspective, what looks like accelerated expansion from a distance might be, at least partly, a side effect of living in a universe whose structure is radically uneven once you actually do the math honestly.

How Singularities Could Mimic Dark Energy

To understand how singularities might replace dark energy, think about traffic on a highway. If you only looked from an airplane and averaged the speed of every car, you might conclude traffic is flowing smoothly. But if there are several nasty bottlenecks and pileups, the local stop-and-go behavior can completely change the overall pattern in ways a simple average misses. Cosmologists face a similar problem: they often use equations that assume the universe is smooth, then average later, instead of averaging the complex geometry first and only then computing how it evolves.

Physicists who emphasize singularities and strong inhomogeneities argue that this order of operations matters. Singular regions, like those surrounding black holes, severely curve spacetime and can alter the paths of light and matter on very large scales. When you try to average these effects correctly, you may find that the global expansion looks faster than you would predict from a smooth model without ever needing a separate dark energy term. In other words, the singular structures might be doing the heavy lifting, and the so-called acceleration might be, at least partly, a mirage created by how we model the lumps.

The Mathematics Problem: Averaging a Lumpy Universe

Behind all this lies a stubborn mathematical headache: general relativity is nonlinear, which means that the sum of many small solutions is not necessarily a solution itself. You cannot simply take a universe full of black holes, average their densities, and expect to get the same result as if you first smoothed things out and then solved Einstein’s equations. This is the heart of what some researchers call the backreaction problem: the idea that small-scale structure can feed back into and modify large-scale expansion.

Singularities make this even harder, because they push spacetime curvature to extreme limits where familiar approximations break down. A few theorists have tried to build models in which the combined gravitational impact of singular environments reproduces the effects typically attributed to dark energy. These models are technically demanding and often rely on heavy numerical simulations or idealized setups, but they show that our intuition about “averaging” the universe may be overly naive. If those corrections turn out to be big enough, a lot of what we call dark energy might actually be an artifact of ignoring the real complexity of cosmic geometry.

What the Observations Actually Say So Far

Observationally, the standard dark energy model still does a remarkably good job describing the data, which is why many cosmologists are reluctant to abandon it. Measurements of the cosmic microwave background, large-scale galaxy surveys, and gravitational lensing roughly point to a universe whose expansion history looks as if some smooth, repulsive component is present. When researchers test many alternative models, the simple dark energy picture frequently comes out ahead in terms of fitting the widest range of observations with the fewest adjustable ingredients.

However, cracks and tensions have appeared, especially in measurements of the current expansion rate (the Hubble constant) and the growth of structure over time. Some of these discrepancies could hint that our model is incomplete or that subtle effects from inhomogeneities and singularities are sneaking in. The challenge is that singularity-based or backreaction models must not only remove dark energy but also still match the detailed patterns we see in the sky. So far, no singularity-driven alternative has clearly outperformed the standard model across all data sets, but the fact that a few are even competitive keeps this debate alive.

Why Some Physicists Are Not Ready to Let Go of Dark Energy

From the outside, it might seem obvious: if dark energy is mysterious and singularities are real, why not just blame the expansion on the latter? But for many working cosmologists, the situation is not that simple. Dark energy, while puzzling, slots neatly into equations that already fit a staggering variety of measurements, and it does so with a small number of free parameters. Replacing it with singularity-driven effects often requires more complicated models, subtle assumptions about averaging, and heavy computational work that is not yet as mature or widely tested.

There is also a practical culture issue: large experiments and surveys are already designed around the standard model, using dark energy as the baseline against which deviations are measured. That does not mean singularity-based explanations are wrong, only that they must offer clear, testable predictions and show where the standard model fails in a way that cannot be patched. Until a singularity-focused approach delivers a decisive observational win or a clear argument that dark energy is unnecessary, a lot of researchers will see it as an intriguing but unproven alternative rather than a replacement.

A Personal Take: Why This Debate Matters for How We Think

What fascinates me most about this debate is less the final verdict and more what it says about how we do science. Cosmology asks us to describe an entire universe we can never step outside of, using averages and models that inevitably cut corners. Arguing about whether dark energy is real or whether singularities and inhomogeneities can do the job forces us to confront the limits of those shortcuts, especially when dealing with something as messy as the actual distribution of matter and gravity on all scales.

On a more personal level, I find the singularity-based viewpoint oddly comforting, even if it ultimately turns out to be wrong. It suggests that some of the strangest behaviors we see on the largest scales might be rooted in the same gravitational extremes we already know, rather than in an entirely new substance we cannot detect directly. Whether you lean toward the standard dark energy picture or the singularity-driven alternatives, the real value here is that both sides are pushing us to design sharper observations and more honest mathematical tools. In the end, the universe does not care which story we prefer; it just behaves the way it behaves.

A Universe Still Up for Debate

The idea that singularities, not dark energy, might drive the expansion of the universe is more than a quirky side note; it is a serious attempt to rethink how we connect local extremes of gravity to the global behavior of spacetime. While the standard dark energy model still provides the most widely accepted fit to current observations, singularity-focused approaches highlight real gaps in our understanding of averaging, inhomogeneity, and the nonlinear nature of Einstein’s theory. Those issues do not disappear just because the standard model works well in practice.

As new surveys map billions of galaxies and sharpen our measurements of cosmic expansion, we will learn whether singularities and their backreaction are a subtle correction or a fundamental missing piece in our picture of the cosmos. For now, the universe sits before us like a half-solved puzzle, with dark energy on one side of the table and singularity-driven ideas on the other, both insisting they belong in the final picture. Which one would you have guessed is really pulling the cosmic strings?