Not long ago, many astronomers quietly assumed the universe’s expansion was slowing down, like shrapnel from a blast gradually tugged back by gravity. Then, in the late nineteen‑nineties, two teams studying dying stars stumbled on a result so unsettling that some thought they had made a mistake: distant galaxies were not just receding, they were speeding up. That shocking twist forced cosmologists to revive an old idea with a new name – dark energy, an invisible ingredient that behaves less like matter and more like a restless pressure in the fabric of space itself. Today, dark energy sits at the center of one of science’s biggest puzzles, an enormous question mark hanging over nearly three quarters of the cosmos. We can map its fingerprints in the sky, build billion‑dollar instruments to chase it, and argue about it in conference halls, but we still cannot say with confidence what it actually is.

The Night the Universe Changed Direction

The story of dark energy begins, surprisingly, with small points of light that explode only once. In the nineteen‑nineties, astronomers used a special kind of stellar explosion called a Type Ia supernova as a cosmic yardstick, assuming its consistent brightness would reveal how quickly the universe was expanding at different times. The expectation was straightforward and comforting: over billions of years, gravity from all the matter in the universe should have slowed the expansion like a car coasting uphill. Instead, when researchers looked at supernovae in very distant galaxies, they appeared dimmer than expected, as if the galaxies had been flung farther away than their models allowed. That mismatch was not a rounding error – it suggested that, on the largest scales, some unknown influence was overpowering gravity.

For a while, the result felt almost too weird to accept, so scientists attacked it from every angle. Were the supernovae changing with cosmic time in ways no one had noticed? Was dust making them look dimmer than they really were? After years of cross‑checks, improved data, and independent methods, the unsettling conclusion held up: the universe’s expansion is accelerating. That realization did not just tweak existing theories; it upended them, forcing cosmologists to admit there was a missing piece in their cosmic recipe. That missing piece, now called dark energy, quickly went from an odd idea to the main driver of the universe’s long‑term fate.

The Ghost in Einstein’s Equations

In a twist that would probably make him cringe and smile at the same time, Albert Einstein had already written something like dark energy into his equations a century earlier. To keep the universe static – the prevailing belief at the time – he added a term now called the cosmological constant, a sort of built‑in pressure that could counterbalance gravity. When observations later showed that the universe was expanding, Einstein reportedly abandoned this term and moved on, considering it a kind of mathematical kludge. However, once the late‑twentieth‑century supernova data pointed toward an accelerating cosmos, physicists dusted off the cosmological constant and asked whether it might represent a real physical feature of space.

In the modern view, the cosmological constant is often interpreted as vacuum energy, a faint but persistent energy associated with empty space itself. In this picture, every cubic centimeter of space has a tiny amount of energy that does not dilute as the universe expands but keeps pushing outward. The trouble is that when physicists try to calculate this vacuum energy using quantum field theory, the numbers explode into absurdity, predicting a value wildly higher than what cosmic observations allow. That staggering mismatch – sometimes called the worst prediction in physics – is one reason dark energy remains such a profound mystery. Even when the equations seem to fit the big picture, they clash horribly with the underlying microphysics.

Reading the Sky for Hidden Clues

If dark energy cannot be bottled or sampled, cosmologists do the next best thing: they read its tracks across the sky. One major line of evidence comes from the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow of the Big Bang that now bathes the universe in microwaves. Tiny ripples in this ancient light encode how fast the universe was expanding when it was just a few hundred thousand years old, and how much matter and energy it contained. When researchers combine that information with the way galaxies clump together today and the brightness of distant supernovae, they get a remarkably consistent story that demands something like dark energy. It is as if the universe is leaving us careful notes, but in a language we are still learning to translate.

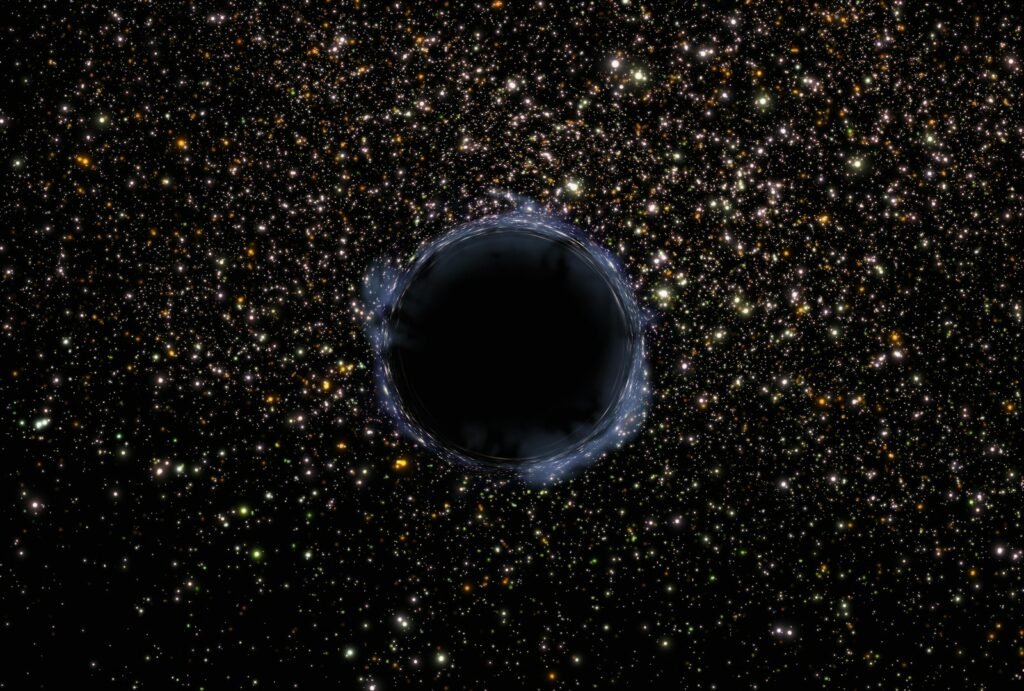

Modern surveys go even further, using vast maps of galaxies to measure how cosmic structures have grown over billions of years. Patterns known as baryon acoustic oscillations – relic sound waves frozen into the distribution of galaxies – act as giant standard rulers that can reveal how the expansion rate has changed over time. Scientists also watch how clusters of galaxies form and how gravity bends light from even more distant objects, a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. Each of these methods offers a different angle on dark energy’s behavior, and when they line up, confidence grows that the mystery is real, not a statistical fluke. Yet the very consistency of these clues sharpens the frustration: we know dark energy is there, but it continues to hide what it is.

Beyond a Simple Cosmological Constant

Although the simplest explanation for dark energy is a constant energy density filling space, many cosmologists suspect the story might be richer. Some theories propose a new field that permeates the universe, somewhat like the Higgs field, but one that can change slowly over cosmic time. In these models, often grouped under the label of quintessence, dark energy could have been weaker or stronger in the past and might evolve in the future. Others explore the possibility that Einstein’s theory of general relativity itself breaks down on the largest scales, and that what we call dark energy is really a sign that gravity behaves differently across billions of light‑years than it does in our solar system. These ideas are not wild guesses; they are carefully constructed alternatives designed to be testable with precise observations.

To sort out these possibilities, researchers focus on a key quantity known as the equation‑of‑state parameter, which roughly describes how dark energy’s pressure relates to its energy density. A true cosmological constant should have a fixed value for this parameter, while dynamical fields or modified gravity models might cause it to vary with time. Large‑scale projects, from space telescopes to ground‑based observatories, are now being built or upgraded to measure this behavior with extraordinary precision. The goal is not just to describe the acceleration but to catch it in the act of changing, if it ever does. A tiny deviation from the constant case could point the way toward an entirely new chapter in fundamental physics.

Why This Invisible Force Matters

It might be tempting to think of dark energy as a remote curiosity, something that matters only for galaxies and grand equations, but its implications reach much closer to home. For one thing, dark energy dominates the universe’s energy budget, accounting for roughly about two thirds of everything, while ordinary matter – the stuff that makes us – contributes only a small fraction. That alone is a humbling fact, a reminder that we live in a cosmic minority. Understanding dark energy is also crucial for predicting the ultimate fate of the universe, whether space will expand forever, coast into a slow freeze, or tear itself apart in a more violent finale. Every scenario depends on how this mysterious component behaves over the next trillions of years.

Our effort to understand dark energy also echoes a deeper human pattern: whenever we push to the extremes of scale, we uncover new rules. Just as atomic physics reshaped our view of matter and quantum theory rewrote the behavior of particles, dark energy hints that our grasp of gravity or spacetime is incomplete. Comparing today’s situation with earlier eras, we are again staring at anomalies that refuse to fit neatly into existing frameworks. The way we respond – by refining our measurements, questioning assumptions, and building better theories – will shape not just cosmology, but our broader understanding of reality. In that sense, dark energy is less a distant mystery and more a mirror held up to the limits of our knowledge.

The New Generation of Cosmic Experiments

To move beyond broad strokes, scientists are building a fleet of experiments capable of scrutinizing dark energy from multiple angles at once. New space telescopes are being designed to map billions of galaxies, tracing how cosmic structures grow and how quickly the universe stretches at different epochs. On the ground, powerful survey telescopes scan huge swaths of the sky night after night, capturing the flickers of supernovae and the subtle distortions of gravitational lensing. Together, these instruments act like complementary senses, each sensitive to a different aspect of dark energy’s influence. The hope is that by overlapping their strengths, they can expose tiny discrepancies that point to new physics.

Alongside these grand observatories, advances in data analysis and simulation are just as crucial. Cosmologists now run vast numerical experiments on supercomputers, evolving virtual universes forward in time under different assumptions about dark energy and gravity. By comparing these synthetic skies to real observations, they can test whether any given model survives or fails. At the same time, improved detectors and better calibration methods aim to squeeze out hidden biases that could masquerade as exotic effects. It is a slow, iterative process, but it is precisely this patience and insistence on cross‑checking that gives the field its credibility.

Living in an Accelerating Cosmos

On human timescales, dark energy is completely silent, its influence spread so thinly that it has no practical effect on everyday life. Yet on the scale of billions of years, it reshapes the story of everything. If the acceleration continues, distant galaxies will slip out of view as their light is stretched beyond detectability, leaving our descendants, if they exist, in a cosmic island almost empty of visible neighbors. Star formation will dwindle, and the universe will grow colder and darker, more like a vast museum where the lights are slowly being dimmed. Understanding this future is not about morbid curiosity; it is about recognizing the real context in which our brief history is unfolding.

There is also something unexpectedly intimate about confronting dark energy’s enormity. Many people describe a strange mix of insignificance and connection when they first learn that most of the universe is made of things we cannot see or touch. For me, that feeling is less about cosmic despair and more about permission to be curious, to accept that not everything has been wrapped up with a tidy bow. Living in an accelerating cosmos means living with unanswered questions on the grandest scale imaginable. Instead of being a defect, that uncertainty can be a feature – a reminder that exploration is still possible, and that the universe is not done surprising us.

How You Can Follow and Support the Search

Even if you never point a telescope at the sky, there are simple ways to engage with the unfolding story of dark energy. One is to seek out trustworthy, in‑depth coverage of new results, rather than settling for quick headlines that frame every update as a dramatic crisis. Many observatories and space missions maintain public outreach programs, open data portals, and live‑streamed events where scientists explain their work in accessible language. By tuning into those channels, you can watch the process of discovery unfold in real time instead of only catching the final announcements. Sharing that journey with friends, students, or family can help make the cosmos feel less distant and abstract.

If you want to go a step further, you can also support organizations that champion basic research and science education. That might mean contributing to planetariums, university outreach programs, or nonprofits that provide classroom resources and teacher training. Some projects invite citizen scientists to help classify galaxies or spot supernovae in telescope images, turning curiosity into real data that professionals can use. And perhaps most importantly, you can defend the idea that exploring questions without immediate practical payoff – like the nature of dark energy – is still a worthwhile, deeply human endeavor. In a universe where most of the energy is hidden from view, keeping that curiosity alive is its own quiet act of resistance.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.