Imagine waking up one day to learn that the Sun, the most familiar thing in our sky, might not be an only child. Somewhere, far beyond the planets we know, there could be a dark, hidden twin that quietly shaped the Solar System, stirred up comets, and maybe even nudged the conditions that allowed us to exist. It sounds like science fiction, but it’s actually rooted in serious astrophysics and decades of curious, sometimes controversial, research.

We don’t have proof of a literal second Sun glowing in the distance, and that’s important to say upfront. But we do have a growing body of evidence that most stars form in pairs, and that our own star’s early history might not be as simple as we once thought. The idea of an unseen solar sibling or long-lost twin offers a surprisingly powerful way to tie together mysteries about comets, distant planets, and even the strange architecture of the outer Solar System. Let’s unpack what scientists really mean when they talk about a hidden twin of the Sun – and why the concept refuses to go away.

A Shocking Idea: The Sun Probably Wasn’t Born Alone

Here’s the first surprising twist: when astronomers look out into star-forming regions today, they find that single stars like our Sun are actually the exception, not the rule. Roughly about half of all Sun‑like stars are found in binary or multiple systems, and for very massive stars the fraction is even higher. In dense star nurseries, it’s common to see newborn stars paired up, dancing around each other in long, slow orbits like cosmic figure skaters who just met.

This has led some researchers to suspect that our Sun, too, may have had a companion in its youth. The idea is not that there’s another bright star hiding behind the Moon; instead, it could have been a widely separated partner, possibly torn away by gravitational encounters with other stars early in our Solar System’s life. When you think of the Sun as once part of a stellar duo, suddenly some odd features of our system stop feeling like isolated quirks and start to look like clues in a much bigger story.

Nemesis, Planet Nine, And Other Cosmic Suspects

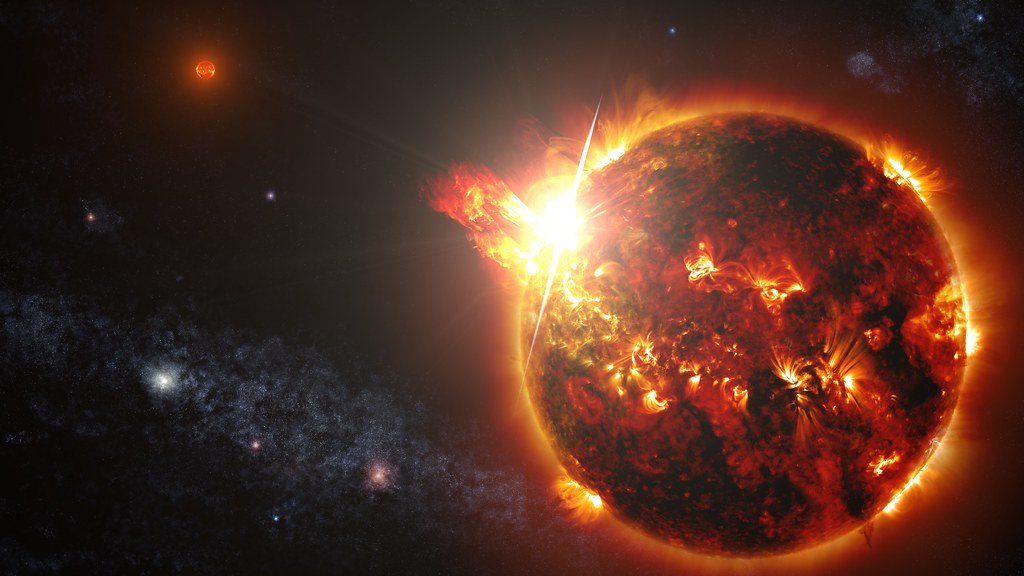

The modern fascination with a hidden solar partner really took off in the late twentieth century, with a bold idea sometimes called the Nemesis hypothesis. Some scientists noticed that mass extinction events on Earth seemed to cluster in roughly repeating intervals, and they wondered if a dim distant companion star might periodically shake up the Oort Cloud – the enormous reservoir of icy bodies far beyond Pluto – sending comet showers inward. This hypothetical star, Nemesis, would be incredibly faint and far away, perhaps a red dwarf or a brown dwarf, making it tricky to spot.

So far, extensive sky surveys, including infrared missions designed to find dim, cool objects, haven’t found convincing evidence for such a star on the proposed orbit. But the search for Nemesis indirectly opened the door for other ideas, including today’s ongoing hunt for Planet Nine: a proposed massive planet orbiting far beyond Neptune. While Planet Nine is not a star and not a true “twin” of the Sun, the impulse behind it is similar – to explain the strange, clustered orbits of distant icy objects with the gravitational pull of something big, dark, and missing from our maps. In that sense, Nemesis and Planet Nine are like two versions of the same urge: to blame the Solar System’s weirdness on a hidden heavyweight lurking at the edge.

Why Scientists Think A Long-Lost Sibling Makes Sense

Beyond specific objects like Nemesis or Planet Nine, there’s a broader, quieter argument that the Sun almost certainly formed with at least one sibling. Star formation simulations suggest that when a cloud of gas collapses under gravity, it often fragments into multiple clumps, each igniting into a star. Observations of young stellar clusters back this up: you see doubles, triples, and loose groups everywhere. From that perspective, a star forming solo is like a child being the only one in an entire neighborhood – not impossible, but statistically odd.

Recently, some researchers have proposed that the Sun’s “twin” might not be bound to us anymore, but could be a lost sibling that shared the same birth cluster. That means it would have formed from the same cloud of gas, maybe at a similar time, with roughly the same chemical makeup, before drifting off through the galaxy in a slightly different direction. If we could find that sibling today, it would be like finding a long‑lost family member who remembers your early childhood. By comparing its composition and age, we’d learn a lot about what the Solar System looked like before the planets were fully formed.

Comets, The Oort Cloud, And The Fingerprints Of A Hidden Partner

One of the strangest features of our Solar System is the Oort Cloud, a vast, nearly spherical shell of icy bodies that probably extends a light‑year or more from the Sun. It’s like a ghostly halo of leftovers from planetary formation, loosely gravitationally bound and extremely easy to disturb. A passing star, a giant molecular cloud, or a binary companion in a huge, slow orbit could all nudge these icy objects, sending some of them falling toward the inner Solar System as long‑period comets. These are the dramatic visitors that sometimes appear with long tails, swinging in from far beyond Neptune.

The idea of a distant twin, or an early‑life binary companion, helps explain how the Oort Cloud got puffed up into a sphere instead of remaining a flat disk like the planets. Gravitational tugs from another star could have scattered icy bodies in all directions, seeding the enormous cloud we infer today. Even if that companion is gone now – kicked away by interactions with other stars in the Sun’s birth cluster – its fingerprints might remain in the architecture of the outer Solar System. In that sense, every bright, long‑period comet you see in the night sky could be a quiet echo of the Sun’s complicated family history.

Dark Twins: Brown Dwarfs And Invisible Companions

When people hear “solar twin,” they often imagine another Sun‑like star blazing in the distance, but reality might be far murkier. A potential companion could be a brown dwarf – an object too big to be a planet and too small to sustain full‑blown hydrogen fusion like a star. Brown dwarfs glow softly in infrared light but can be almost invisible in ordinary visible light, which is why they’re sometimes nicknamed failed stars. If such an object sat tens of thousands of times farther from the Sun than Earth, it would be a genuine ghost to casual observation.

Infrared sky surveys in the past couple of decades have dramatically improved our understanding of brown dwarfs near the Solar System. They’ve discovered many cool, dim objects within a few dozen light‑years, but they haven’t revealed a clear, massive companion in an obvious bound orbit around the Sun. That said, very wide companions on strange paths are hard to rule out completely, especially if they’re relatively low mass. The door isn’t wide open anymore, but it’s not sealed shut either, and that slim space of possibility is where the more speculative versions of a hidden twin still live.

Could A Twin Explain Life-Friendly Conditions On Earth?

The idea that a hidden twin “might explain everything” is obviously an exaggeration, but there’s a serious kernel hidden inside the drama. The history of life on Earth has been shaped by both gentle stability and violent disruption: long periods of calm climate, interrupted by impacts, extinctions, and dramatic shifts. A companion star or lost sibling could have played a subtle role in this balance, especially by influencing the rate and timing of comet and asteroid impacts. Too many catastrophic hits, and complex life struggles; too few, and you might not get the chemical mixing and occasional resets that push evolution forward.

On a more indirect level, thinking about a solar twin forces us to ask why our planetary system ended up relatively orderly compared to some exoplanet systems we see. Many stars have giant planets on wild, close‑in orbits, or wildly tilted configurations that look nothing like our neat chain of worlds. If an early companion helped sculpt or disturb the protoplanetary disk, it might have nudged conditions just enough to favor the long‑term stability Earth needed. We don’t have a smoking gun here, but the twin‑Sun idea acts like a lens, focusing our questions about why the Solar System is so strangely hospitable in the first place.

The Search Today: From Gaia To Future Sky Maps

In the past, looking for a hidden solar twin was like hunting for a needle in a galactic haystack with a dim flashlight. Today, space observatories have turned that flashlight into a stadium floodlight. The European Gaia mission is currently mapping the positions, motions, and brightness of well over a billion stars in our galaxy with extraordinary precision. By combining this data with chemical fingerprints from ground‑based telescopes, astronomers are actively searching for “solar siblings” – stars that likely formed from the same original cloud as the Sun.

What they’re looking for are stars that share almost identical chemical compositions and ages, and whose motions in the galaxy could plausibly trace back to the same birthplace. A few promising candidates have been found, but none have yet been crowned as a definitive solar sibling. At the same time, ongoing surveys continue to tighten the limits on any still‑bound companion lurking in the deep outer Solar System. We’re living in a moment where the question of the Sun’s twin is moving from speculation toward testable science, and the next decade of data could finally reveal whether our star’s early life was quietly shared with a partner we’ve never seen.

What A Hidden Twin Really Tells Us About Ourselves

In the end, the story of the Sun’s potential twin is less about a specific invisible star and more about how we relate to the universe. For a long time, we liked to imagine our Solar System as uniquely tidy and self‑contained, with one star in the middle and a few well‑behaved planets circling around. Modern astronomy has shattered that comforting picture: binary stars are common, weird planetary systems abound, and our own backyard is full of unsolved puzzles. The notion of a hidden twin forces us to accept that even the Sun might have a more complicated emotional backstory than we ever guessed.

On a personal level, I find something oddly moving about the idea that our star may have once had a companion and then lost it to the chaos of the galaxy. It makes the Solar System feel less like a static clockwork and more like a family drama, full of close calls, separations, and long shadows. Whether we eventually confirm a lost sibling, a faint past companion, or nothing at all, the search is already changing how we see our place in the cosmos. If even the Sun might have a twin we can’t see, what else about our universe is hiding in plain sight, just waiting for us to learn how to look?