In server rooms humming quietly beneath cities and in brain labs lit by the cold glow of MRI scanners, a question that once belonged to science fiction is edging toward serious scientific debate: could we ever upload a human mind? The idea sits at the collision point of neuroscience, computer science, philosophy, and raw human fear of death. For some, a digital afterlife promises a kind of technological salvation; for others, it is a chilling threat to what it means to be human. Right now, the science is nowhere near “mind uploading” in any practical sense, yet research into brain mapping, neural prosthetics, and AI simulations is moving faster than our moral vocabulary. Whether we welcome or dread it, the possibility forces us to ask a very old question with very new tools: what, exactly, is a self?

The Hidden Clues Inside a Living Brain

Walk into a modern neuroscience lab and you will not find anything that looks like a glowing, digitized soul; instead, you see sprawling screens of brain scans, rows of electrodes, and endlessly scrolling code. These are the instruments scientists are using to decode the patterns of electrical and chemical activity that make up our thoughts, memories, and sense of “I.” Technologies like functional MRI, high-density EEG, and invasive electrode arrays can already track brain activity linked to simple decisions, intentions, and even rough images a person is seeing. The clues are faint but real: research teams have reconstructed coarse video frames and written words a person is viewing, based on nothing but recorded brain activity. In parallel, brain–computer interfaces are letting paralyzed patients move cursors, robotic arms, and even spell out sentences purely with their thoughts.

Yet these tools capture only the tiniest fraction of what the brain is doing at any moment, and they do it at resolutions far too low for anything like full “mind capture.” A single human brain contains roughly as many neurons as there are stars in the Milky Way, each making thousands of connections, constantly changing with experience. Capturing a true “snapshot” of a person’s mind would mean tracking not just the structure of these networks, but the dynamic state of every relevant cell and synapse. The hidden clues we have today are like a child’s stick figure compared with a living, breathing portrait. Still, every year brings a new, slightly sharper sketch – and that is enough to fuel both hope and alarm.

From Sci-Fi Dream to Lab Bench: How Uploading Entered Serious Debate

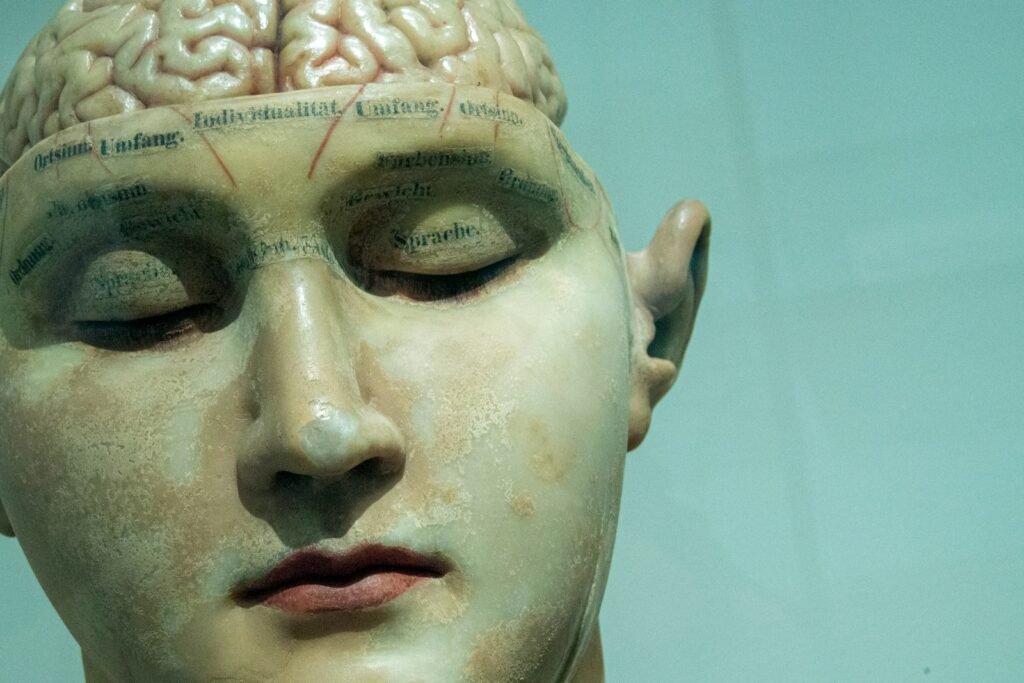

For much of the twentieth century, the idea of uploading consciousness lived comfortably in the pages of novels and on cinema screens, an entertaining but distant fantasy. What changed was not a sudden breakthrough in “soul extraction,” but a series of smaller, very tangible advances in mapping and mimicking pieces of the brain. In the early twenty-first century, projects to simulate slices of rat cortex and then larger networks of neurons showed that at least some brain-like activity could be recreated in silicon. Efforts to map the full connectome – the wiring diagram – of simple organisms, such as worms and flies, added to the sense that, in principle, the circuitry of a mind might be charted.

Alongside these efforts, the rise of powerful machine learning systems that can imitate human conversation, recognize faces, and generate images blurred the line between “computer” and “mind-like behavior” in the public imagination. Companies began talking openly about backing “mind uploading” research or offering future digital preservation, even if the underlying science was aspirational at best. For many neuroscientists, the rhetoric ran far ahead of the data, but the debate had already shifted. Instead of asking whether mind uploading was pure fantasy, serious researchers began asking a more uncomfortable question: what, exactly, would have to be true about the brain and consciousness for this ever to work?

What Would It Really Mean to Upload a Mind?

On paper, the basic recipe sounds almost straightforward: scan the brain at extraordinary detail, build a digital model that reproduces every relevant connection and property, and then run that model on a powerful computer. In theory, if the simulation is accurate enough, the resulting system should behave like the original person, remember their life, and respond in their style. But each piece of that recipe hides huge unknowns. Neuroscientists still argue about which aspects of the brain are essential for consciousness: is it just the connectivity and firing patterns of neurons, or do we need to capture the subtle chemistry of glial cells, blood flow, and even quantum effects in ion channels, as some fringe theories propose?

There is also a brutal technical snag: today’s best brain scanners cannot begin to capture every synapse and molecule in a living human brain without destroying it. Some proposed methods for “whole brain emulation” imagine preserving a brain post-mortem at extremely fine resolution, then reconstructing it digitally, which raises an obvious and disturbing paradox: the biological original does not survive the process. Even if a future technology allowed non-destructive scanning, we would still face a philosophical cliff edge. If a digital copy of you wakes up and insists it is you, with your memories and your fears, is that continuity of self – or a convincingly animated echo?

Why It Matters: Death, Identity, and Who Gets to Live Forever

This is not just an abstract thought experiment for late-night debates; it cuts straight into how we think about death, grief, and justice. For centuries, every human culture has evolved rituals and beliefs to help us accept that life ends, from burial traditions to ideas of spiritual afterlives. A viable path to digital continuation would tear at those frameworks, offering a new answer to the most human of fears: the fear of not being. At the same time, it risks creating a two-tier reality in which those with enough money, data access, and technological infrastructure get a shot at “extended existence,” while everyone else remains subject to ordinary mortality.

There are sharp practical worries as well. A digital mind would depend entirely on infrastructure: servers, electricity, maintenance teams, corporate or governmental policies. That leads to unsettling scenarios in which a person’s continued “life” might be subject to subscription fees, ownership disputes, or even political control. Unlike traditional inheritance or funeral costs, the ongoing survival of a digital self could become a recurring bill. There is also the ethical nightmare of consent: what counts as permission to preserve and run a model of someone’s mind, especially if they can no longer change that decision? These questions make mind uploading less of a tech novelty and more of a civil rights frontier in waiting.

Brains, Bodies, and the Question of the Soul

One of the most emotionally charged objections to digital afterlives comes from a simple intuition: we are not just brains in jars. Our sense of self is shaped by hormones, gut bacteria, heartbeat, and the feedback of moving through space, touching, tasting, and aging. A purely digital version of “you” running in a server rack might replicate your memories and conversational style, but would it feel anything like the lived experience of a human in a body? Some philosophers argue that detaching mind from flesh would create something fundamentally new – a kind of alien intelligence built from human data rather than a genuine continuation of the person.

On the other hand, proponents of mind uploading often point out that much of what we consider “personality” already shows resilience through changes in our bodies: we remain ourselves despite injuries, illnesses, and even radical medical interventions. From this view, the brain is the essential substrate, and the body is an important but ultimately replaceable interface. Personally, I find myself torn. When I imagine a loved one existing only as a chat window and an animated avatar, it feels both comforting and heartbreakingly hollow, like talking to a reflection that can smile back but never hold your hand.

Global Perspectives: Who Owns a Digital Afterlife?

If mind uploading ever inches closer to reality, it will not arrive into a cultural vacuum. Different societies already hold deeply varied beliefs about death, souls, and the acceptability of posthumous manipulation of the body. In some traditions, tampering with the dead beyond minimal burial rites is seen as profoundly disrespectful, while others embrace organ donation and medical study as acts of service. Digital preservation of consciousness – or even of a realistic mind simulation – would likely provoke similarly diverse responses, from enthusiastic adoption to outright bans. The global map of acceptance might end up resembling our patchwork attitudes toward euthanasia, genetic editing, or surrogacy.

Another fault line will run between nations that control the infrastructure and intellectual property behind such technologies and those that do not. Imagine a world where a handful of powerful corporations and governments effectively oversee humanity’s “cloud of the dead.” Questions of data sovereignty, cultural ownership of ancestors’ stories, and cross-border legal conflicts would be inevitable. Some communities might choose to build local, culturally grounded “memory archives” instead of full-blown consciousness emulations, preserving voices and decision patterns without claiming that the dead truly live on. The choices we make as a global community will determine whether digital afterlives, if they come, deepen existing inequalities or open new forms of connection.

The Future Landscape: Technologies, Roadblocks, and Dystopian Detours

Looking ahead from 2025, mind uploading remains, by any sober assessment, a distant prospect, but the building blocks are under active development. Advances in nanoscale imaging, improved brain–computer interfaces, and AI models capable of mimicking specific individuals’ writing and speech patterns are all converging. Some startups already offer services that train AI avatars on a person’s messages, videos, and recordings, creating chatbots that feel eerily like digital ghosts of the living or recently deceased. These avatars are a far cry from true consciousness, but they are close enough to stir real grief, comfort, and ethical discomfort in the people who interact with them.

Technically, the biggest roadblocks are staggering: we would need vastly better scanning techniques, more complete theories of consciousness, and computing architectures orders of magnitude beyond what we have today. Socially, the risks of stumbling into dystopian futures are just as daunting. A world filled with editable, copyable “people files” invites abuses from identity theft at a horrifying new scale to exploitative resurrections of public figures. At the same time, limited forms of digital continuation – carefully regulated and transparently artificial – might help the living process loss or preserve knowledge across generations. The future landscape is not a straight road to digital immortality; it is a branching maze of technical, legal, and emotional choices.

How You Can Engage With the Question – Without Waiting for a Server-Side Afterlife

Most of us are not running brain labs or designing supercomputers, but that does not mean we are bystanders in this debate. The norms we set today around data privacy, biometric information, and AI-generated personas will shape the environment any future mind-uploading technology grows into. You can start by paying closer attention to where your data goes, how your likeness and voice are used, and what terms you agree to when you hand over fragments of yourself to apps and platforms. Supporting strong digital rights laws and transparent AI regulation is, in a quiet way, also a vote on what kinds of digital selves will be possible decades from now.

On a more personal level, there is something grounding about considering your own preferences before the technology exists. Would you want a realistic chatbot model of you to comfort your family? A public archive of your decisions, values, and stories? Or would you prefer that your traces fade, leaving only memories in human minds? Talking about these questions with friends and family might feel strange at first, but so did early conversations about organ donation and living wills. In the end, mind uploading – or whatever comes closest to it – will not just be a scientific milestone; it will be a reflection of what we decide a good human life, and a good human death, should look like.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.