Walk into a crowded city street and you feel certain you’re seeing the world as it truly is: the cars, the faces, the neon signs, the threat of that bike whizzing too close to the curb. Yet neuroscience is quietly, and sometimes uncomfortably, dismantling that confidence. What we experience as reality is not a direct feed from the outside world but a carefully constructed story written inside our skulls. For researchers exploring consciousness, this is both a thrilling opportunity and a profound challenge. If the brain is a storyteller, not a camera, the real question becomes: how much of what we call “the world” is actually us?

The Hidden Clues: Your Brain Is Guessing, Not Just Seeing

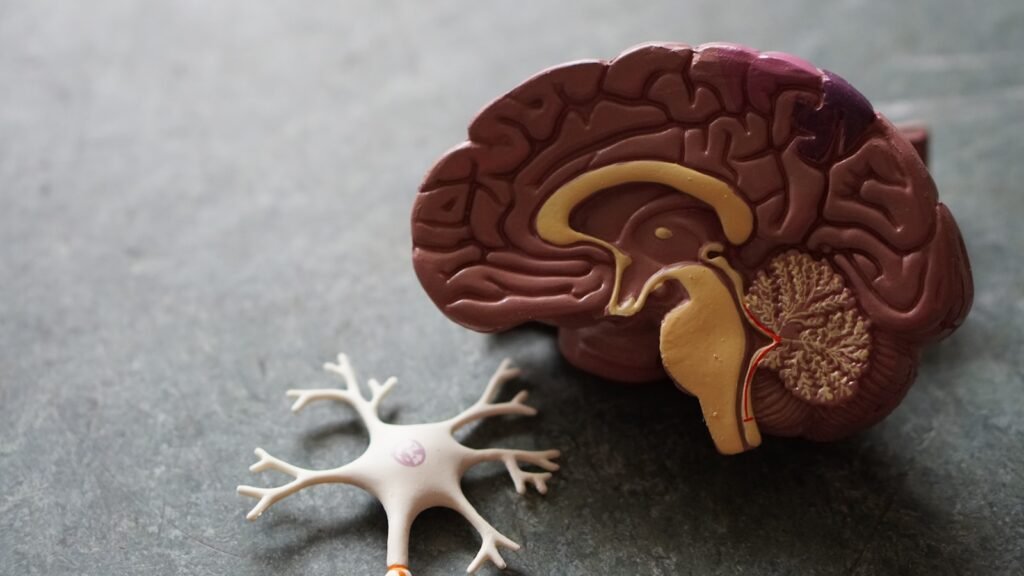

One of the most surprising clues about perception is how easily it can be tricked. Classic visual illusions, like the checkerboard where two identical shades look completely different, reveal that the brain is constantly correcting and interpreting incoming signals rather than just relaying them. Neuroimaging studies show that regions of the brain involved in vision light up even when people merely imagine an object, suggesting that perception and imagination share similar circuits. This blurring of lines hints at a deeper truth: your brain is always predicting what should be out there and then checking whether the incoming data fits. When the guess and the input match closely enough, you get the feeling of a solid, stable reality.

Researchers now often describe perception as a form of “controlled hallucination” anchored by sensory information. The brain uses past experiences, expectations, and context to fill in gaps and smooth over noise. That is why you can read a sentence with letters missing or recognize a friend in bad lighting almost instantly. It also explains why, when predictions go wrong, the world can suddenly feel strange or threatening, as seen in some psychiatric conditions. Instead of thinking of your eyes as windows, it may be more accurate to think of them as tiny webcams feeding raw data into a massive prediction engine.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Brain Scanners

Humans have wrestled with the idea that reality might be filtered or distorted for a very long time. Ancient philosophers in Greece and India already suspected that the senses were unreliable guides to truth, more like shadows on a cave wall than the real thing. For centuries, though, this was mostly a matter of speculation and metaphor, lacking the tools to probe what was really happening inside the head. That changed dramatically in the twentieth century with the arrival of electrophysiology, which allowed scientists to record the electrical chatter of neurons. Suddenly, the brain’s inner conversations about the outside world were not just philosophical ideas but measurable signals.

Today, powerful imaging methods like fMRI and MEG let researchers watch whole networks of brain regions coordinating as people see, hear, imagine, and dream. These tools have revealed that sensory areas are woven into loops with higher-level regions that deal with memory, expectation, and decision-making. In other words, what you sense and what you believe are constantly feeding into one another. Experiments where scientists decode what someone is looking at from brain activity alone show just how structured and interpretable these patterns can be. We are now in an era where the old philosophical hunch – reality is a mental construction – is backed by dense streams of data rather than just clever arguments.

The Predictive Brain: Reality as a Best Guess

A leading framework tying all this together is known as predictive processing. In this view, the brain is less a passive receiver and more a restless prediction machine, always trying to minimize the gap between what it expects and what actually arrives through the senses. It builds internal models of the world – how light behaves, how voices sound, how your own body should feel – and constantly updates them based on experience. When something unexpected happens, such as a sudden loud bang behind you, your brain rapidly learns to adjust its model or explain the event away. Over time, this process gives you the comforting impression of a world that is stable and understandable.

This approach also offers a powerful way to think about disorders of perception and belief. If the brain weights prediction too heavily, it might override sensory evidence and cling to rigid expectations, potentially contributing to delusions. If it trusts sensory noise too much, everything can feel chaotic or overwhelming, feeding into anxiety or certain hallucinations. The predictive brain framework does not reduce people to equations, but it does give scientists a structured way to link brain activity, experience, and behavior. In a very real sense, the story your brain writes about reality depends on how it balances these competing demands: stay open to the world, but not so open that you drown in uncertainty.

Bodies, Senses, and the Self We Think We Are

Perception is not just about the world “out there”; it is just as much about the body “in here.” Experiments like the rubber-hand illusion, where people begin to feel ownership over a fake hand that is stroked in sync with their real one, show how malleable the sense of self can be. Brain regions that integrate touch, vision, and internal bodily signals work together to maintain a coherent feeling of “this is me.” When that integration goes awry, as in some neurological or psychiatric conditions, people may feel detached from their bodies or as if parts of themselves are not truly theirs. These experiences, once dismissed as purely psychological, now have clear neural signatures.

At the same time, research on the gut–brain axis and interoception – the sensing of internal bodily states – has revealed that perception is deeply influenced by what is happening under the skin. The brain constantly monitors heartbeats, breathing rhythms, and hormonal signals, weaving them into your emotional and perceptual life. A racing heart can sharpen your sense of danger; a calm, slow breath can make the world seem gentler and more predictable. This means that reality, as you experience it, is not just shaped by the outside environment but by a chorus of internal signals. The feeling of being a self in a world is a continuous negotiation between body and brain.

The Consciousness Question: What Does “Real” Even Mean?

All of this naturally leads to an unsettling but fascinating question: if the brain constructs reality, what exactly is consciousness doing in the mix? Neuroscientists have mapped many of the brain circuits that correlate with being awake, aware, or in specific mental states, but there is still no consensus on why subjective experience exists at all. Some theories focus on information integration, arguing that consciousness arises when information is combined in certain complex ways. Others emphasize the idea of the brain modeling not just the world but itself, creating a kind of inner theatre of attention. None of these ideas has yet achieved universal acceptance, but they have fueled a burst of experiments and debates.

What is becoming harder to defend is the comfortable assumption that consciousness is just a passive mirror of the outside world. Instead, many scientists now see it as part of an active inference process, a way for the brain to keep track of its own predictions and errors. From this perspective, your conscious reality is like a live news feed about what your brain thinks is going on, both in the environment and in your body. That news feed can be biased, incomplete, or flat-out wrong, but it is still the only channel you have. The philosophical implications are profound: if our realities are brain-made, then understanding consciousness is not a luxury question; it is central to understanding what it means to exist at all.

Why It Matters: Health, Justice, and Everyday Life

The idea that the brain creates reality might sound abstract, but its consequences are decidedly concrete. In mental health, for example, conditions like depression, anxiety, and psychosis can be reinterpreted as disruptions in how the brain predicts and interprets the world. This shift opens new treatment possibilities that aim not only to change chemistry but also to gently reshape prediction patterns through therapy and training. In pain research, scientists have shown that expectation and context can dramatically amplify or dampen pain signals. That means a patient’s reality of suffering is shaped not only by tissue damage but by beliefs, memories, and surroundings.

There are also implications for the legal system and social conflict. If perception is an active construction, eyewitness testimony becomes far less reliable than most juries assume. Two people can, in good faith, experience the same event differently because their brains are using different priors, shaped by culture, history, and personal trauma. On a more everyday level, recognizing that everyone is living inside a slightly different constructed reality can invite a bit more humility. The person who seems unreasonable may simply be operating from a different predictive model. Understanding that our brains are not neutral recorders but biased editors can be a quiet act of empathy.

The Future Landscape: Brain Tech, Virtual Worlds, and Ethical Storms

As we get better at reading and even influencing brain activity, the gap between neuroscience and technology is closing fast. Brain–computer interfaces are already allowing some people with paralysis to move robotic limbs or type by thought alone. Virtual reality systems are becoming more immersive, hijacking the brain’s predictive machinery to create worlds that feel startlingly real. Future devices might combine these trends, delivering finely tuned sensory inputs that the brain treats as indistinguishable from everyday life. When your brain accepts a synthetic environment as reality, the philosophical debate suddenly becomes a design question.

This new landscape brings ethical challenges that are hard to overstate. If companies or governments learn to subtly nudge predictive processes – through targeted media, tailored environments, or neurotechnology – the line between persuasion and manipulation could blur. There are also questions about identity when people spend large chunks of time in alternate realities that feel completely convincing. At the same time, powerful tools for mental health treatment, rehabilitation, and learning may emerge from this same science. The stakes are global: as we learn to build and bend realities from the inside out, societies will need robust conversations about consent, privacy, and what counts as an authentic life.

How You Can Engage With Your Constructed Reality

While all of this might sound like something only labs and tech companies can touch, individuals have more influence than they think. Simple practices that tune your attention – such as mindfulness, deliberate breathing, or even just stepping away from constant digital noise – can shift how your brain filters the world. Paying close attention to moments when your expectations are wrong, like mishearing a word or misjudging a person, can become informal experiments in prediction. Over time, this builds a kind of perceptual literacy: a sense that what you experience is real for you but not necessarily the only way things could appear. That small mental step can make you more curious and less defensive.

You can also support the science that is pushing these questions forward. That might mean following reputable neuroscience reporting, participating in research studies when possible, or backing organizations that promote open, ethical brain research. Even talking with friends and family about how perception works can help spread a more nuanced view of reality. Instead of assuming that others “just don’t see the facts,” you can explore how different histories and bodies produce different worlds. In a time of polarized realities and information overload, understanding that the brain creates reality is not just a fascinating scientific insight – it is a practical tool for living with others.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.