Imagine waking up every morning not to emails or alarms, but to the question: will I survive today? For hundreds of thousands of years, that was normal life for our ancestors. Every scar on their bodies, every tool they carved, every fire they lit left tiny fingerprints on the humans we’ve become.

We like to think we’re completely modern, scrolling screens and streaming shows, but under the surface we’re still running on very old software. The way we love, fear, cooperate, fight, tell stories, and even stress-eat at night was shaped by people who spent their lives dodging predators, hunting wild animals, and trying not to starve. Their challenges didn’t just shape history; they’re still writing the code of our daily lives.

Living on the Edge of Hunger

For most of human history, there were no full fridges, no corner stores, no emergency snacks in the desk drawer. Food was uncertain, and the next good meal was never guaranteed. Our ancestors survived long stretches of scarcity, and their bodies adapted in ways that still live inside us, from how we store fat to how we crave sugar and salt when we’re stressed.

This is a big reason our brains light up for calorie-dense foods and why it feels easier to eat too much than too little. When food was rare, overeating when it was available was a survival strategy, not a bad habit. Today, that ancient wiring meets a world of endless junk food, and suddenly many of us are fighting instincts that once kept our families alive.

Predators, Peril, and the Birth of Anxiety

Our early ancestors lived in a world filled with real, physical threats: big cats, hidden snakes, rival groups, sudden storms. If you didn’t notice the rustle in the grass or the shadow at the edge of camp, you might not live long enough to pass on your genes. So evolution favored brains that were quick to spot danger, even if they sometimes overreacted.

That same hair-trigger alarm system still runs today, just in a different environment. Instead of lions, we jump at notifications, harsh emails, or social rejection, but our body still reacts as if something could physically hurt us. What we call anxiety, hyper-vigilance, or “overthinking” is often an ancient survival mode playing out in a modern world that almost never requires us to run for our lives.

Cold Nights, Harsh Climates, and Human Toughness

Many of our ancestors had to survive ice ages, droughts, and dramatic climate swings that would terrify most of us today. They learned to track seasons, migrate long distances, store food, make clothing, and build shelters that could keep them alive through brutal winters or scorching heat. Those who couldn’t adapt simply didn’t survive to have children.

That history is written in our bodies: our ability to sweat efficiently, our layered fat distribution, our wide range of skin tones designed to balance sun exposure and vitamin production. Even our cultural habits, like gathering around warmth or sharing hot drinks in cold weather, echo a time when getting temperature management wrong was a death sentence instead of just an inconvenience.

Cooperation: Our Greatest Survival Tool

Unlike many predators, we weren’t especially fast, strong, or well-armed with claws or fangs. What we had was each other. Early humans hunted in groups, shared food, watched each other’s children, and nursed the injured. Groups that cooperated were far more likely to survive famine, attacks, or disasters, and that cooperation shaped the kind of brains we evolved.

This is why humans are so deeply social and why isolation feels painful on a level that goes beyond simple boredom. We’re wired to read faces, interpret tone, form alliances, and care what others think. Modern office politics, social media drama, and neighborhood gossip are oddly distorted echoes of older patterns: figuring out who’s on our side, who might betray us, and where we belong in the group.

Fire, Tools, and the Expanding Human Brain

When our ancestors learned to control fire, everything changed. Cooking made food easier to chew and digest, unlocking more energy from the same amount of meat or plants. With that extra energy, our brains could grow larger and more complex, and we could spend less time endlessly chewing raw food and more time thinking, planning, and communicating.

The rise of tools, from simple stone flakes to finely shaped blades and needles, took that even further. Tools allowed us to hunt larger animals, shape clothing, build better shelters, and manipulate our environment instead of just enduring it. That constant problem-solving and tinkering laid the foundation for the creative, tool-obsessed species that now builds rockets, smartphones, and ridiculously complicated coffee machines.

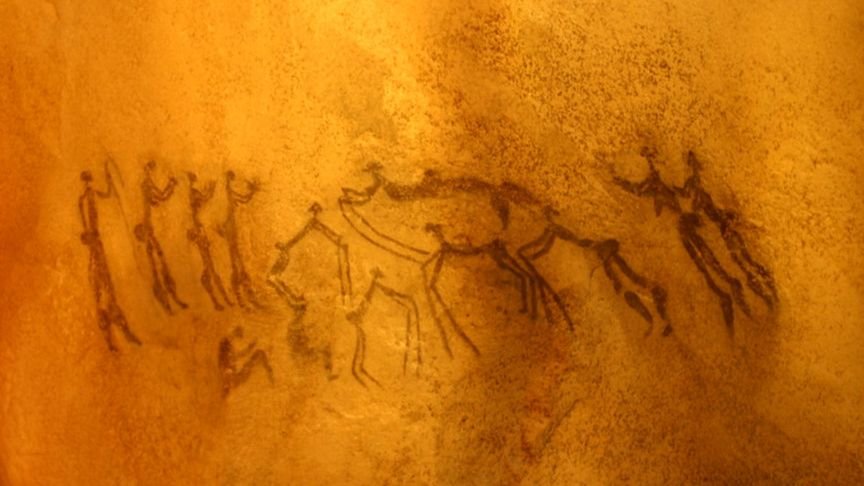

Storytelling, Myths, and Shared Meaning

Imagine a small group of people sitting around a fire, telling stories about a dangerous river crossing, a generous ancestor, or a strange pattern in the stars. Those stories were not just entertainment; they were memory, instruction, warning, and identity all woven into one. Groups with strong shared stories could pass on survival knowledge and keep people united across generations.

That is why our brains are still so addicted to narrative. We remember stories better than raw facts, we bond over shared legends, and we instinctively try to turn our own lives into some kind of coherent plot. From ancient myths to modern movies, we’re still doing what our ancestors did: using stories to make a confusing, dangerous world feel a little more understandable and a little less lonely.

Grief, Love, and the Cost of Deep Attachment

Archaeologists have found some of the earliest evidence of humans carefully burying their dead, sometimes with objects that seemed meaningful. That suggests something powerful: our ancestors loved deeply enough to mourn, to remember, and to treat the dead with respect rather than simple disposal. Attachment came with a real emotional cost, but it also glued groups together in ways that improved survival.

We still carry that tendency toward fierce connection and painful loss. The joy of bonding with family, friends, or partners and the devastation when we lose them is part of the same ancient pattern. Strong relationships made the difference between surviving and dying in harsh environments, so it makes sense that love and grief both run so deep, even when the threats we face now are no longer saber-toothed cats and sudden storms.

From Survival Instincts to Modern Lives

When you look closely, modern life is layered over instincts that were honed in caves, grasslands, and forests, not cities and screens. Our cravings, fears, emotional reactions, and social habits often make more sense when seen through that older lens. The very traits that sometimes frustrate us today once helped keep our ancestors alive long enough to build the world we now live in.

Understanding that connection doesn’t excuse our bad behavior, but it does help explain why change can feel so hard and why some patterns seem almost baked into us. We’re not broken; we’re just ancient animals trying to navigate a brand-new kind of world with very old wiring. Knowing where that wiring came from might be the first real step toward deciding what we want to keep and what we’re finally ready to outgrow.