Under the turquoise seas of Indonesia’s Raja Ampat archipelago, a paradox exists: the very minerals driving the global green energy revolution are destroying one of Earth’s most biodiverse marine environments. Called the “Amazon of the Seas,” Raja Ampat boasts a rainbow of marine life and 75% of the coral species found worldwide. But nickel mining necessary for electric vehicle (EV) batteries has destroyed forests, contaminated rivers, and caused landslides, so transforming this biological paradise into a battlefield between conservation and climate change.

Legal challenges and a planned nickel smelter threaten to rekindle damage even with recent government actions to revoke mining permits. One wonders if the global drive for clean energy justifies the loss of a marine paradise.

The Nickel Boom: Fueling EVs at Nature’s Expense

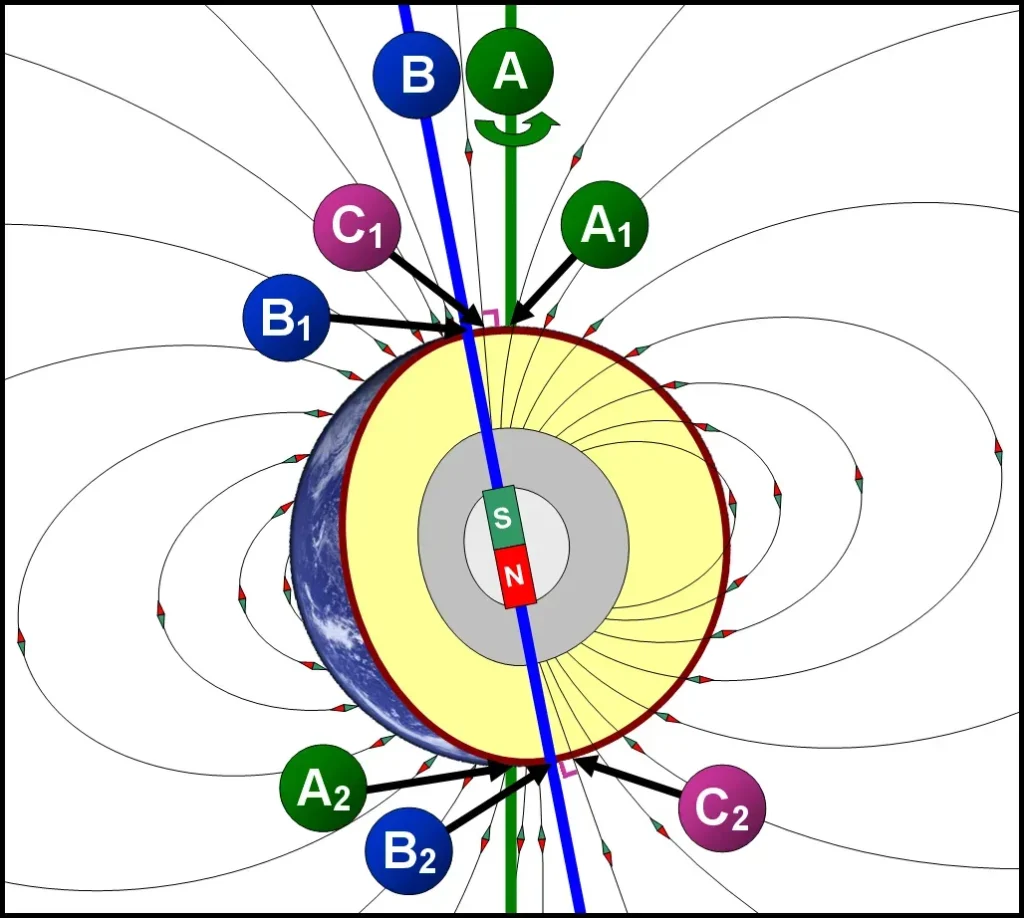

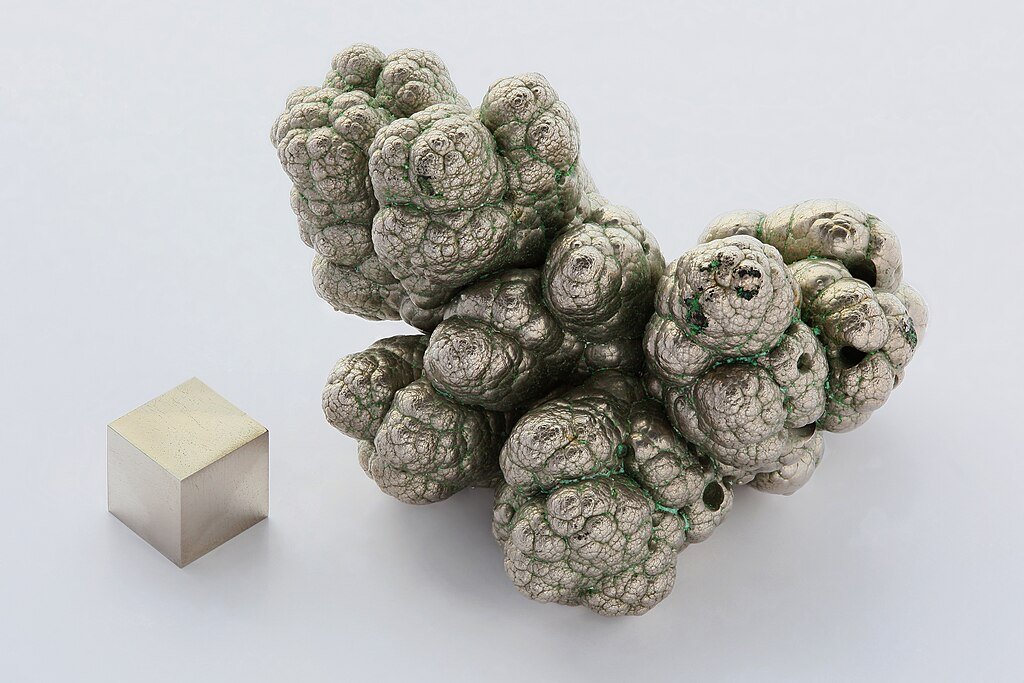

Driven by EV batteries, which could consume 40% of world nickel production up from just 4% a decade ago, nickel demand is set to explode 65% by 2030. With Raja Ampat’s premium grade deposits in the crosshairs, Indonesia, the top nickel producer in the world, provides 48% of all supplies.

Still, the price is astounding. Since 2020, satellite images show 500 hectares of forest loss equivalent to 700 football fields along with coral reef smothering from sediment runoff. Worse, mining concessions span three-quarters of Kabaena Island, where near processing facilities deforestation has doubled.

Unexpected angle: Although nickel is praised as a green metal, its extraction results in 4–500 times more carbon emissions than first believed from neglected effects of deforestation.

“The Sea Is Dirtier Than Before”: Pollution and Broken Livelihoods

For Indigenous Sawai fisher Max Sigoro, the sea no longer serves him. “The fish stock was plentiful before. Now the water is contaminated, and security runs us away,” he says, detailing reddish runoff from coal plants running smelters 8 and oily sludge. Nearby hot wastewater from captive coal plants burning more coal than Spain or Brazil yearly has killed fish and caused skin infections.

Rivers running brown with silt on land force farmers like Felix Naik to dig wells. ” Should rain fall, the water becomes muddy. We worry about heavy metals,” he says, repeating studies connecting mining to poisonous runoff.

Land Grabbing and Coercion: The Human Toll

Alleged land grabs and intimidation surround the $15 billion nickel complex IWIP. Maklon Lobe, a sawai farmer, describes police pressuring him to sell his 38-hectare plot for 15% of its value while businesses preload destruction of his trees.

Denied Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), indigenous people suffer existential threats. Activist Adlun Fikri notes: “We bear the cost for global net-zero ambitions.”

Legal Loopholes and the Smelter Threat

Three companies are suing to resume operations even though Indonesia withdrew four of the five mining licenses in Raja Ampat in June 2025. A planned nickel smelter in Sorong supported by Chinese investors could thus spark demand for Raja Ampat once more.

Greenpeace issues a warning: ” revoked mines will reactivate if the smelter runs. Where else can the nickel originate?”

The Climate Irony: Coal-Powered “Green” Nickel

Twelve new coal plants at IWIP will be used for nickel processing, producing 3.78 gigabytes yearly, so compromising EV carbon savings. Research analyst Krista Shennum says, “It’s an unacceptable false solution.”

Halmahera’s 2.04 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalent emissions from nickel mining equaled 440,000 gas-powered vehicles.

Can the Cycle Be Broken?

There are answers, but they come with challenges.

- EV behemoths like Tesla and Volkswagen have to check vendors for rights violations and deforestation.

- High-pressure acid leaching and bioleaching could reduce the impact of mining.

- Policy changes: Indonesia has to enforce FPIC and stop building more coal plants.

As coral ecologist Dr. Mark Erdmann points out, “The nickel dilemma is horrible. To what extent damage are we ready to tolerate?” The response could decide whether Raja Ampat stays a sacrifice zone or a sanctuary.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.