Imagine stepping into a forest where every leaf, every flower, every towering tree has grown in harmony for thousands of years. British Columbia’s landscapes are a living mosaic of native plants, each perfectly adapted to its home, silently shaping the world around us. Yet, as our cities swell and wild spaces shrink, the simple act of planting native species has become a beacon of hope—uniting science, beauty, and community in a powerful movement to heal the land. Have you ever wondered how your garden, balcony, or neighborhood park could help restore the wild heartbeat of this extraordinary province?

The Rich Diversity of British Columbia’s Native Flora

British Columbia is a botanical wonderland, boasting one of the most diverse ranges of native plants in Canada. From the misty rainforests of the Pacific coast to the dry grasslands of the Interior, each region shelters its own unique collection of species. Western redcedar, Douglas-fir, and salal flourish along the coastal rainforest, while ponderosa pine and sagebrush define the drier Okanagan valleys. In alpine meadows, vibrant wildflowers like lupines and paintbrushes brave the short, intense summers. Each plant has evolved to thrive in its native soil, climate, and ecosystem, creating an intricate tapestry of life. This diversity not only supports wildlife but also provides resilience against changing environmental conditions. When we choose native plants, we celebrate and protect this astonishing natural legacy.

Why Native Plants Matter for Local Ecosystems

Native plants play a starring role in the health of British Columbia’s ecosystems. Unlike imported species, they have deep relationships with local insects, birds, fungi, and mammals. For example, the Garry oak ecosystem supports over 100 rare plant species and countless pollinators, some of which can’t survive anywhere else. Native shrubs such as salmonberry and elderberry offer crucial food sources for bears, birds, and bees. Their root systems stabilize soil, prevent erosion, and filter water, quietly working beneath our feet. When non-native plants take over, these delicate networks unravel, threatening the survival of entire communities of life. Choosing native species helps restore balance, offering a lifeline to plants and animals struggling to hold on.

Coastal Forests: Nature’s Green Cathedrals

The coastal forests of British Columbia are breathtaking, draped in moss and alive with the earthy scent of cedar and spruce. Here, native plants have adapted to high rainfall, mild temperatures, and dense shade. Sword ferns unfurl beneath ancient giants, while red huckleberry and salal form tangled green carpets. Epiphytic mosses and lichens cloak the branches, creating microhabitats for insects and birds. These forests act as carbon sinks, slowing climate change, and as sanctuaries for endangered species like the marbled murrelet. By planting native understory species in parks and yards, we can echo the complexity and resilience of these natural cathedrals even within urban boundaries.

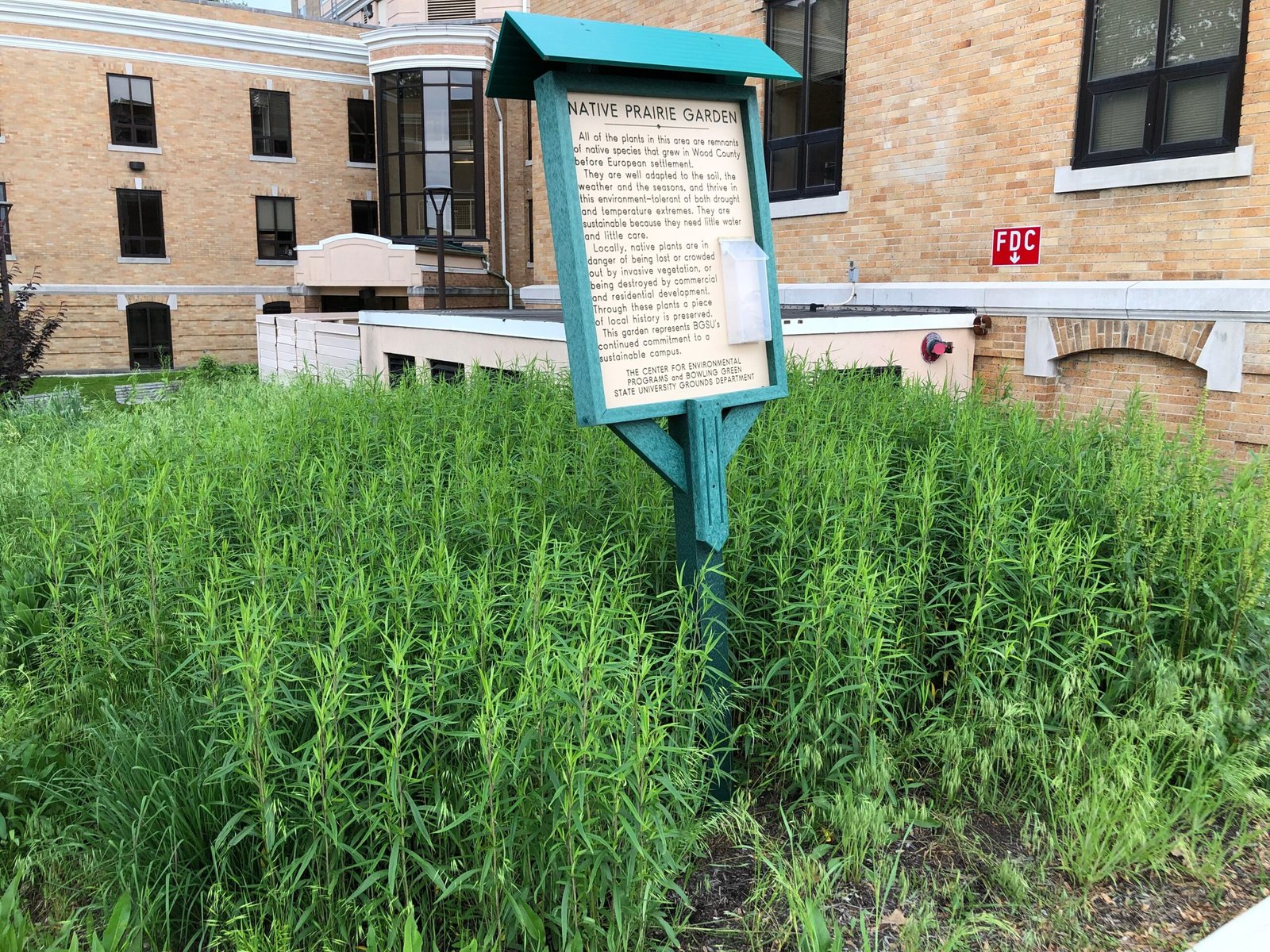

From Wild Meadows to Urban Gardens

Urban spaces often feel disconnected from nature, but native plants can bridge this divide. Even a small patch of native wildflowers or grasses can attract bees, butterflies, and songbirds, transforming sterile lawns into lively ecosystems. Vancouver’s pollinator corridors, for example, use native plants to connect green spaces, allowing wildlife to move safely through the city. Home gardeners are replacing exotic ornamentals with native species like Oregon grape, kinnikinnick, and nodding onion, bringing bursts of color and life to patios and balconies. These choices turn ordinary spaces into miniature meadows, nurturing biodiversity where it’s needed most.

Native Planting as a Climate Solution

Planting native species is more than an act of beauty—it’s a powerful climate solution. Native trees and shrubs store carbon more efficiently, thanks to their deep roots and long lifespans. Coastal Douglas-firs and western hemlocks can lock away carbon for centuries, helping to buffer the impacts of rising greenhouse gases. Native plants also require less water, fertilizer, and maintenance, reducing the carbon footprint of gardens and city landscapes. As heatwaves and droughts become more common, native species are better equipped to withstand these stresses, keeping ecosystems robust in a changing world.

Restoring Wetlands and Riparian Zones

Wetlands and riverbanks are lifelines for many species in British Columbia, and native plants are key to their survival. Willows, sedges, and rushes stabilize banks, prevent erosion, and filter pollutants from the water. These plants create habitat for frogs, fish, and migratory birds, many of which are threatened by habitat loss. Restoration projects along the Fraser River and Okanagan Lake have shown how quickly wildlife returns when native vegetation is replanted. Even urban streams benefit when native shrubs and trees are planted along their banks, offering shade and shelter to aquatic life.

Challenges of Invasive Species

The spread of invasive plants like Scotch broom, Himalayan blackberry, and English ivy poses a growing threat to native ecosystems. These aggressive species outcompete native plants for light, water, and nutrients, often forming dense monocultures where little else can survive. Invasive plants can alter fire regimes, soil chemistry, and hydrology, leading to long-term ecological damage. Removing invasives and restoring native species is a painstaking but vital process, often requiring community involvement and ongoing stewardship. Every native plant replanted is a step towards reclaiming lost landscapes.

Indigenous Knowledge and Native Planting

For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples in British Columbia have stewarded native plants for food, medicine, and cultural traditions. Traditional ecological knowledge recognizes the deep interconnections between plants, people, and place. Camas, salmonberry, and cedar are woven into stories, songs, and seasonal harvests. Today, many restoration projects are guided by collaboration with Indigenous communities, honoring their expertise and relationship with the land. Learning from these traditions deepens our understanding of native planting as an act of respect, reciprocity, and healing.

Designing Native Gardens for All Spaces

Anyone can create a native garden, no matter the size of their space. Start by observing the light, soil, and moisture in your chosen area—nature offers the best planting cues. Grouping plants with similar needs mimics natural plant communities and reduces maintenance. For shady spots, try sword fern and false lily-of-the-valley; for sunny areas, try yarrow, wild strawberry, or nodding onion. Mix in native grasses for texture and movement. Even container gardens and green roofs can host native species, bringing the wild closer to home. The result is not just a garden, but a living tapestry that evolves with the seasons.

Community Initiatives and Citizen Science

Across British Columbia, passionate individuals and groups are championing native planting. Local nurseries now offer a wider range of native species, while schools, parks, and community gardens are embracing restoration projects. Citizen science initiatives invite people to track pollinators, monitor plant growth, or map invasive species, turning curiosity into action. These grassroots efforts build community, inspire stewardship, and spark a sense of wonder in people of all ages. When we work together, even small changes can ripple outward, transforming neighborhoods and restoring hope for the future.

The Lasting Impact of Native Planting

Planting native species is a gift to future generations—a living legacy that outlasts trends and seasons. Each tree, shrub, and wildflower planted today shapes the landscapes of tomorrow, ensuring that British Columbia’s natural beauty and biodiversity endure. Native planting is not just about gardening; it’s about participating in the ongoing story of this remarkable province. What will you plant, and how will your choices echo through the forests, meadows, and cities that you call home?