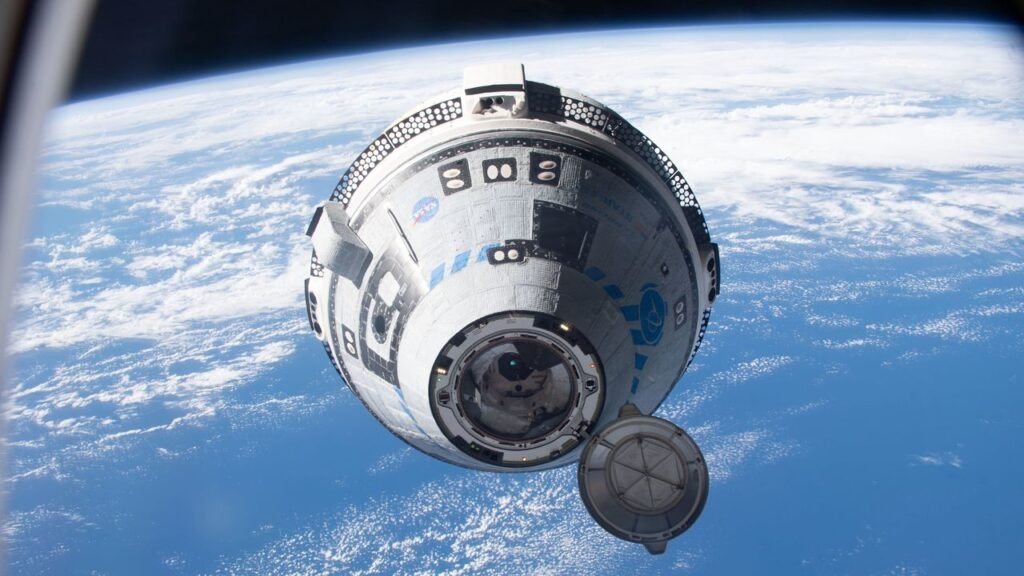

Thrusters Fail, Control Slips Near the Space Station (Image Credits: Cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net)

NASA formally classified Boeing’s first crewed Starliner mission as a “Type A” mishap, highlighting profound risks that nearly turned a routine test flight into tragedy.[1][2]

Thrusters Fail, Control Slips Near the Space Station

Astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore confronted chaos roughly 24 hours after liftoff when five of Starliner’s maneuvering thrusters shut down during approach to the International Space Station.[3] The spacecraft lost full “six degrees of freedom” control, threatening docking and crew safety. Crew members intervened manually, recovering four thrusters through troubleshooting and securing a linkup.[2]

Launched June 5, 2024, from Cape Canaveral, the mission aimed for an eight-to-14-day stay but stretched to 93 days amid helium leaks in seven of eight manifolds and propulsion vulnerabilities. Starliner returned uncrewed in September 2024, while Williams and Wilmore waited aboard the station until a SpaceX Crew Dragon brought them home in March 2025. Both later retired from NASA.[1][4]

Unpacking the ‘Type A’ Label and Its Gravity

NASA defines a Type A mishap as the most severe, encompassing events with over $2 million in damages, vehicle loss, or life-threatening loss of control – criteria matching Starliner’s thruster cascade and financial toll.[5] This places it alongside the Challenger and Columbia shuttle losses. Agency leaders overlooked the designation initially, prioritizing certification amid schedule pressures.[2]

Administrator Jared Isaacman stressed transparency: “We are formally declaring a Type A mishap and ensuring leadership accountability so situations like this never reoccur.”[1] Associate Administrator Amit Kshatriya added, “We almost did have a really terrible day,” underscoring the razor-thin margin.[2]

Root Causes: Technical Flaws and Oversight Gaps

Investigators pinpointed hardware shortcomings like Teflon poppet extrusion in thrusters from overheating and two-phase oxidizer flow, plus seal degradation from propellant exposure.[3] Qualification tests fell short, lacking flight-like conditions and fault tolerance for deorbit burns. NASA faulted its hands-off contracts, fragmented governance, and culture favoring provider success over rigor.

- Inadequate thermal modeling ignored plume effects and soakback heat up to 300°F.

- Low telemetry rates hampered real-time diagnosis.

- Schedule fatigue led to “use-as-is” risk acceptance.

- Eroding trust sparked unprofessional disputes over crew return plans.

Boeing bore responsibility for systems engineering lapses, while NASA admitted permitting program goals to sway safety calls.[4]

Charting Recovery: 61 Recommendations Ahead

The 311-page report outlined 61 fixes, from enhanced thruster testing and data access to trust-building training and unified decision frameworks.[3] Starliner eyes an uncrewed cargo flight no earlier than April, with crewed returns pending resolutions. Isaacman affirmed commitment to dual providers for low-Earth orbit access.[2]

Corrective steps promise safer human spaceflight, though Boeing’s challenges persist amid the ISS’s 2030 retirement.

Key Takeaways

- Thruster failures risked total loss of control, averted by crew action.

- Shared NASA-Boeing accountability demands cultural and technical overhauls.

- Future flights hinge on rigorous verification to restore trust.

This episode serves as a stark reminder that spaceflight tolerances remain unforgiving. What do you think lies ahead for Starliner and NASA’s commercial crew goals? Tell us in the comments.