Deep below your feet, far beneath the crust and beyond the reach of any drill, lie colossal hidden structures that may have quietly shaped the history of life on Earth. For decades, seismologists have seen strange echoes in earthquake waves hinting at something enormous lurking at the base of the mantle, but no one could agree what they were or why they mattered. Now, a new wave of research is turning those blurry shadows into a sharper picture – and the story they tell reaches all the way to the origins of our continents, our atmosphere, and possibly our own existence. The mystery is no longer just about what is down there; it is about whether these deep-mantle giants have been steering Earth’s evolution from the start. In other words, to understand why there is a habitable world at the surface, we may need to start by listening to the rumblings from nearly three thousand kilometers below.

The hidden clues

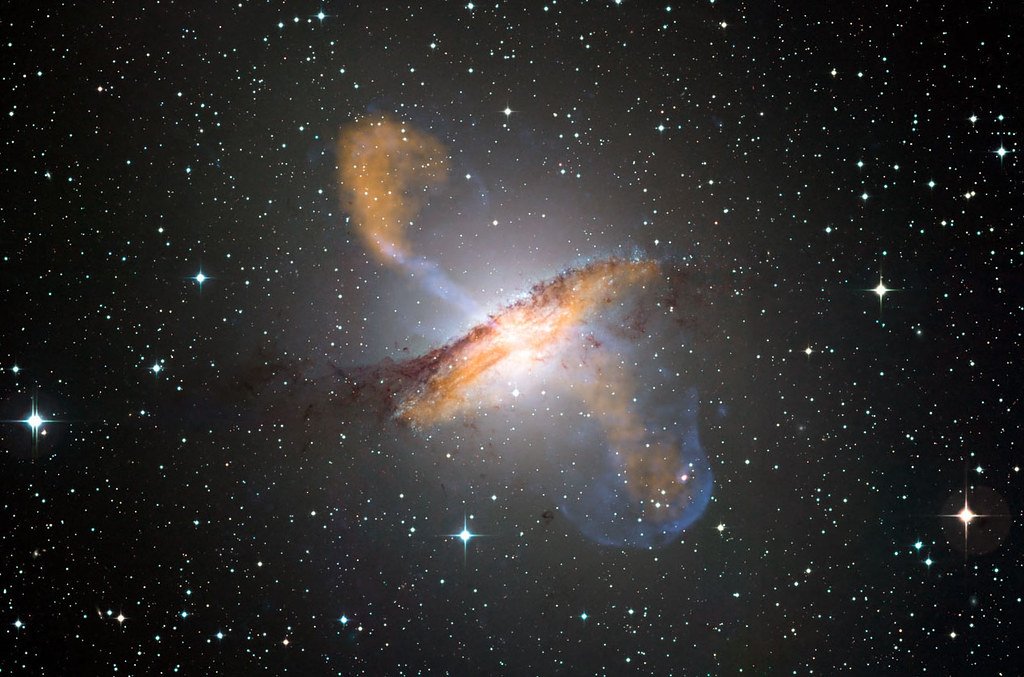

It all started with something that did not fit: seismic waves from big earthquakes kept slowing down in two vast regions near the bottom of the mantle, one beneath Africa and one beneath the Pacific. To seismologists, that slowdown meant those regions were made of something denser or hotter – or both – than the surrounding rock, but the patterns were too strange to dismiss as simple blobs of hot mantle. These zones, now known as large low–shear velocity provinces, or LLSVPs, are staggeringly huge, each the size of a continent turned upside down and buried above Earth’s core. For a long time, they were treated as an oddity in the data, a curiosity that might matter only to deep-Earth specialists. Yet the more precisely researchers measured them, the more it looked like these were not random lumps but key players in Earth’s interior architecture.

Imagine an upside-down mountain range made of ultradense, partially molten rock, draped along the top of the molten outer core; that is roughly what these structures seem to be. They rise hundreds to thousands of kilometers into the mantle and have steep, cliff-like edges rather than fading smoothly into their surroundings, which suggests they have distinct compositions rather than being just hotter mantle. Over the last decade, more detailed seismic imaging has revealed fine structure along their tops and margins, including ultra-low velocity zones that may be thin layers of almost magma-like material. This kind of intricate pattern is not what you would expect from a simple heat blob – it looks more like an ancient, evolving feature that has been sculpted by the restless flow of the mantle for billions of years. That realization has pushed scientists to ask not just what these giants are, but what they have done to the planet over deep time.

Relics of violent beginnings

Most of us grow up with a fairly tame picture of Earth’s birth: a hot young planet that gradually cooled and settled into place. In reality, early Earth was more like a demolition site in space, slammed by enormous impacts that could melt rock oceans and strip atmospheres in a geological instant. One especially dramatic idea, the giant impact hypothesis, suggests that a Mars-sized body called Theia smashed into the young Earth more than four billion years ago, blasting material into orbit that later became the Moon. That collision would have poured enormous energy into the planet and sprayed alien material deep into the mantle and toward the core. For years, the question was: where did all that extra stuff end up, and does any of it still exist today?

One striking proposal is that the LLSVPs we see now are actually the long-lived graveyards of that impact debris, enriched in elements like iron that make them denser than average mantle rock. In this view, those deep structures would be among the oldest surviving remnants of Earth’s childhood violence, preserved at the base of the mantle like sunken continents. Some lab experiments and computer simulations show that dense, iron-rich material from early impacts could indeed migrate downward and pool above the core, forming piles much like the ones we now infer from seismic images. That would mean these structures are not just mantle features but part of the story of how Earth and Moon formed as a coupled system. It is a dizzying thought: the same disaster that may have given Earth its stabilizing Moon might also have seeded the internal structures that later helped shape our surface world.

How deep structures sculpt the surface world

The connection between something thousands of kilometers down and the landscapes we see every day might sound far-fetched at first. But Earth’s mantle, though solid on human timescales, creeps slowly like very thick honey, constantly carrying heat from the core upward toward the surface. That rising heat drives mantle plumes – columns of hotter rock that can punch through tectonic plates and feed giant volcanic eruptions at the surface. What has excited researchers recently is the growing evidence that many of the most powerful, long-lived plumes seem to originate right at the edges of those deep LLSVP structures. Instead of plumes popping up randomly, they appear to be guided or focused by the geometry of these hidden giants.

This matters because those plumes are linked to some of the most dramatic episodes in Earth’s history. Enormous volcanic outpourings called large igneous provinces, which can cover areas the size of countries or even small continents with lava, are often tied to plume heads rising from these deep sources. Such eruptions have been implicated in past mass extinctions, abrupt climate shifts, and the break-up of ancient supercontinents. In that sense, the deep mantle structures act like slow-motion triggers, setting the stage for events that can reshape oceans, continents, and ecosystems over tens of millions of years. The landscape you see around you today – the placement of continents, mountain ranges, and ocean basins – may owe more than we realized to the shape and position of ancient structures we can never directly touch.

Why it matters for life and habitability

This is where the story turns from geophysics to something more personal: whether these hidden features helped make Earth a world where complex life could arise and persist. Over billions of years, mantle plumes tied to the LLSVPs have likely helped drive cycles of volcanism that release gases into the atmosphere and oceans, including carbon dioxide and other volatiles that help regulate climate. Without such deep-sourced volcanism, Earth might have cooled into a static, geologically dead planet with a thin or unstable atmosphere. At the same time, too much or too frequent plume-driven volcanism could push the climate into extremes, triggering runaway greenhouse conditions or persistent global winters.

Some studies suggest that the locations of the LLSVPs relative to tectonic plates may even influence where supercontinents assemble and break apart. That, in turn, affects ocean circulation, nutrient delivery, and the evolution of ecosystems on land and in the sea. If you view the planet as a long-running experiment in habitability, then these mantle structures look less like passive features and more like slow, deep regulators, nudging the system back and forth between different climatic and tectonic states. One could reasonably argue that the delicate balance Earth has maintained between icehouse and greenhouse conditions owes something to the way heat and materials move through these structures over time. In an indirect but profound way, the fact that you are here reading about them may trace back to their quiet work in the deep interior.

Rewriting Earth’s inner map

For most of the twentieth century, textbooks described Earth’s interior as a set of fairly simple, onion-like layers: crust, mantle, core, with the mantle itself treated as compositionally uniform except for temperature differences. The discovery and growing appreciation of LLSVPs has upended that picture, replacing the idea of a bland mantle with a more intricate world of chemically distinct domains that have survived for billions of years. In practical terms, it means that global models of mantle convection, plate motions, and thermal evolution have had to be rebuilt with these dense piles near the core as central features rather than afterthoughts. When scientists simulate how plates drift, how supercontinents assemble, or how heat leaves the core, the presence and geometry of these structures now play a starring role.

This shift also changes how we interpret the rock record at the surface. For example, geochemists studying volcanic rocks have long found isotopic signatures that did not fit neatly into a simple, well-mixed mantle model. Those odd signatures, rich in certain forms of helium, lead, or neodymium, may now be easier to understand if plumes are tapping ancient reservoirs stored in or around the LLSVPs. Instead of being an embarrassing anomaly, those data become supporting evidence that deep mantle domains have kept some of Earth’s earliest geochemical flavors alive. The net effect is that Earth begins to look less like a thoroughly stirred pot and more like a layered, evolving system where memory of the earliest times never fully disappeared. In science, that kind of conceptual flip often marks a genuine turning point in understanding.

Peering into the deep: tools and breakthroughs

Given that no human-made drill has ever come close to the mantle, let alone the core-mantle boundary, all of this knowledge has been won indirectly, through a combination of clever observation and imagination grounded in physics. The main workhorse is global seismology, which uses the way earthquake waves bounce, bend, and slow down inside Earth to create three-dimensional tomographic images, almost like a CT scan of the planet. As more seismic stations have been deployed worldwide and computational methods have improved, those images have gone from fuzzy blobs to relatively sharp reconstructions of the LLSVPs’ outlines and internal variations. In parallel, lab experiments on minerals at extreme pressures and temperatures, using diamond-anvil cells and powerful lasers, have helped constrain what kinds of compositions and phases could match the seismic data.

On top of that, high-resolution numerical simulations running on supercomputers let researchers test different scenarios: for instance, what happens if you start with a mantle seeded with dense impact debris, versus one that is uniform? Over millions of virtual years, the models can reveal whether such structures survive, drift, or break apart, and how they interact with plumes and plates above. Geochemists then bring another layer of evidence, tracing subtle isotopic fingerprints in volcanic rocks back to possible deep reservoirs. It is a messy, interdisciplinary process, and I find that part oddly reassuring; the picture of these mysterious structures has emerged not from one perfect dataset but from many lines of imperfect evidence pointing in the same direction. That convergence gives the idea real weight, even as details continue to be debated.

Why this deep-mantle mystery matters now

It might be tempting to dismiss all this as an esoteric puzzle about rocks far beyond our reach, but the implications spill out into several urgent conversations we are having about planets and life. For one thing, as astronomers discover rocky exoplanets in astonishing numbers, the question of what makes a planet truly habitable is shifting from simple metrics like distance from a star to deeper issues of internal dynamics. A world without long-lived mantle convection and internal structure like Earth’s might never sustain a stable climate, a protective magnetic field, or the cycling of volatiles essential for life. By understanding how features like LLSVPs emerge and persist, we get a more grounded sense of how rare or common Earth-like conditions might actually be in the galaxy.

At the same time, our own efforts to model future climate and long-term carbon cycles rely, at their foundation, on how carbon and heat move between Earth’s interior and surface over millions of years. Traditional climate discussions often end at the crust or the oceans, but those are just the outermost loops of a much larger system. Deep-mantle structures influence the rate and style of volcanism, the creation and destruction of oceanic crust, and the flushing of carbon between reservoirs. Comparing our current understanding with older, simpler models makes clear how much we once left out – and how that could skew our sense of Earth’s long-term stability. Taking these deep processes seriously is not a luxury; it is part of building a more honest, physically rooted picture of the planet we are actively changing.

The future landscape of deep-Earth research

Looking ahead, the story of these mantle giants is likely to get sharper and stranger at the same time. Plans for denser global seismic networks, including ocean-bottom seismometers, promise clearer images of the core-mantle boundary and the detailed edges of LLSVPs. Advances in waveform modeling and machine learning are already helping scientists squeeze more information out of existing quake data, teasing out tiny signals that used to be lost in the noise. On the experimental side, better high-pressure facilities and synchrotron X-ray sources will refine our understanding of how complex mineral mixtures behave at the crushing conditions deep inside Earth. With each step, the room for hand-waving descriptions of these structures shrinks, forcing more precise, testable theories of their origin and evolution.

There are also more speculative frontiers opening up. Some researchers are exploring how neutrinos or other elusive particles might someday give us independent glimpses of the deep interior, bypassing the limitations of seismic waves. Others are starting to link mantle structure more explicitly to the history of Earth’s magnetic field, which is generated in the core but influenced by how heat escapes through the mantle. The global implications are broad: better models of deep-Earth processes feed into everything from resource exploration to hazard assessment for large volcanic provinces. And as we compare Earth with other rocky worlds in our solar system – Mars with its apparently stalled interior, Venus with its extreme surface conditions – the question of why Earth’s deep engine took the path it did will only loom larger.

How readers can stay engaged with Earth’s deep story

Even though none of us will ever visit the base of the mantle, there are surprisingly direct ways to stay connected to the unfolding science about it. One simple step is to follow and support public-facing geoscience: many seismic networks, geological surveys, and space agencies share accessible updates, visualizations, and explainers about new findings. When you see headlines about big earthquakes, supervolcanoes, or exoplanets, it is worth pausing to ask how the hidden structure of a planet’s interior shapes the story. That mindset shift – from thinking of Earth as a static ball to seeing it as a layered, evolving system – can make news about geology feel far more alive and relevant.

On a more concrete level, supporting science education, from local school programs to museum exhibits and citizen science initiatives, helps ensure that the next generation of researchers has the tools to push this work further. If you are inclined, you can even participate indirectly through projects that involve earthquake data or planetary science, where volunteer classifications and observations feed into real research. The deep mantle may seem remote, but our choices about funding, education, and curiosity all feed into how well we understand it in the decades to come. In the end, these mysterious structures are part of the same planet that grows our food, shapes our coasts, and sets the stage for our climate. Paying attention to them is another way of paying attention to the conditions that let us be here at all.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.