Picture this: Over forty years ago, ‘s rivers and streams fell eerily silent where once playful river otters thrived. These sleek aquatic acrobats had nearly vanished, wiped out by decades of unregulated hunting and habitat destruction. What happened next became one of North America’s most remarkable wildlife comeback stories. In the early eighties, when most of ‘s waterways hadn’t seen a wild otter in decades, something extraordinary began. Scientists, conservationists, and wildlife managers embarked on an ambitious mission that would transform the state’s aquatic ecosystems forever. Today, the sight of an otter’s whiskered face popping up in a creek is no longer rare – it’s a testament to human determination and nature’s incredible resilience.

The Near-Complete Disappearance of a Species

By the early 1980s, Missouri’s river otter population had been reduced to a heartbreakingly small number due to unregulated harvest a century prior. Biologists estimated that only 35 to 70 otters survived in the few remnant swamps and wetlands in Missouri’s Bootheel region. This represented one of the most dramatic wildlife population collapses in the state’s history. Their numbers had remained stagnant for more than 50 years, trapped in small pockets of suitable habitat in southeastern Missouri. The species that once thrived throughout the state’s vast network of waterways had been pushed to the very edge of extinction. Unregulated hunting and habitat destruction continued into the 1970s, making recovery seem nearly impossible without human intervention.

The Bold Louisiana Connection

Beginning in 1982, a total of 845 river otters were reintroduced to Missouri, more than 50 years after extirpation. The source of these otters came from an unexpected place: the bayous and coastal marshes of Louisiana. Most otters were translocated from Louisiana and released at 43 sites across the state. This wasn’t just a simple catch-and-release operation. The first batch came from Louisiana in 1982, fitted with radio-implants for tracking, and released in some of Missouri’s finest wetlands in and around Chariton County in north-central Missouri. The Louisiana otters proved to be hardy pioneers, perfectly suited for Missouri’s varied aquatic habitats. In a few short generations, they made hundreds of new otters that spread out into adjacent duck clubs and borrow ditches.

Explosive Population Growth Beyond All Expectations

The success of Missouri’s otter reintroduction exceeded everyone’s wildest dreams. By 2000, an estimated population of 15,000 to 20,000 otters existed, with density estimates similar to those reported for populations across the continent. This represents one of the fastest carnivore population recoveries ever documented. Their population peaked at more than 15,000, transforming Missouri from a state with virtually no otters to one with a thriving population. Otters now exist in every county of the state, with the statewide population numbers having peaked between 15,000-20,000. This dramatic turnaround occurred in less than two decades – a conservation success story that caught even the experts by surprise.

The Science Behind Success

What made Missouri’s otter reintroduction so successful? Scientists have studied the genetic makeup of these recovered populations to understand their remarkable comeback. The Missouri population showed moderate to high heterozygosity and allelic diversity, similar to that of the source populations. This genetic diversity proved crucial for their adaptability and reproductive success. Researchers detected five distinct genetic clusters distributed throughout eight rivers, with no evidence of isolation by distance. This finding suggested that otters were freely moving and breeding across the landscape, creating a robust, interconnected population. Missouri river otters made a robust recovery despite retaining the genetic signature of the reintroduction, proving that careful planning and sufficient genetic diversity could overcome the challenges of species restoration.

Unexpected Challenges and Controversies

Success brought its own problems. As otter populations exploded, they began showing up in places nobody expected. There is no predator of fish more efficient than river otters, and traveling in groups of two to eight animals, they can devastate fish in a small pond before anyone knows they’re there. Farm pond owners across Missouri suddenly found their carefully stocked fish populations decimated overnight. Conservation agents in the central Ozarks handled more than 500 otter complaints in one year alone. As one local angler put it, “There’s not enough room for otters and fishermen in the Ozarks”. The situation became so heated that the Conservation Department had gone from hero to goat for its “successful” otter restoration program almost overnight.

Finding Balance Through Management

By the mid-1990s, Missouri wildlife officials realized they needed to manage their success story more carefully. The first regulated trapping season was initiated in 1996 to help bring balance back to the state’s rivers and ponds. This decision wasn’t made lightly – it represented a delicate balance between conservation success and practical wildlife management. Despite two court cases forced by national animal rights groups, annual trapping seasons have continued ever since. Missouri trappers became the backbone of management efforts to restore some balance to the otter population. The state learned that successful conservation sometimes requires ongoing management to maintain harmony between wildlife and human communities.

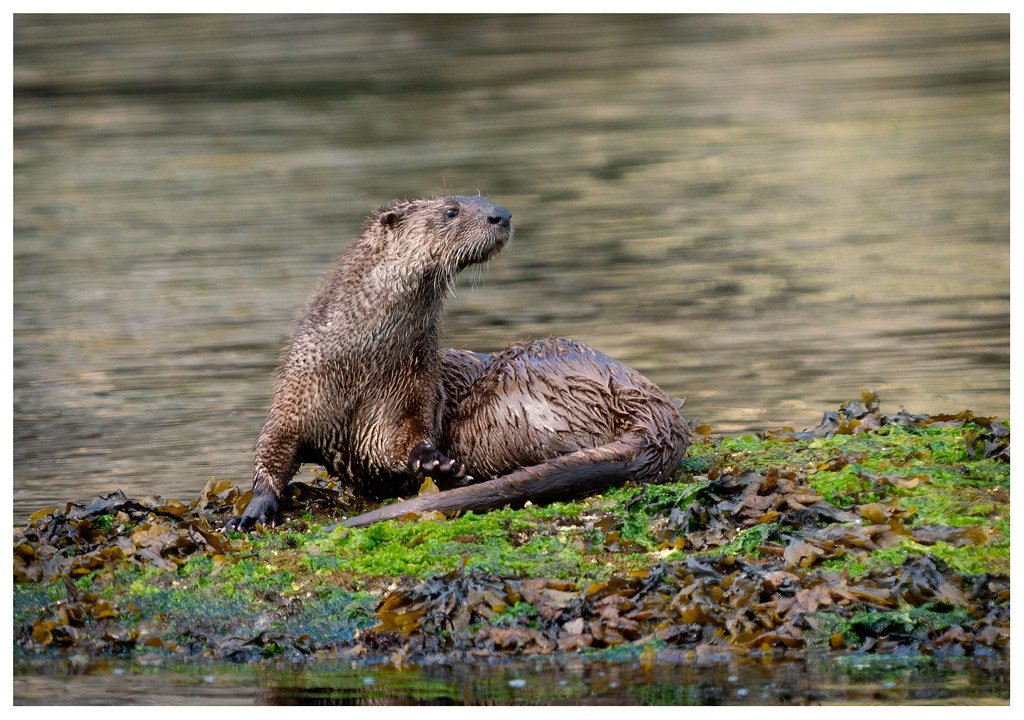

Remarkable Physical Adaptations for Aquatic Life

Understanding why otters succeeded so dramatically in Missouri requires appreciating their incredible physical adaptations. They have streamlined bodies, fully webbed feet, and long, tapered tails that are thick at the base and flat on the bottom. Their ears and nose close when they go underwater, making them perfectly designed for aquatic hunting. Dense, oily fur and regular preening help insulate them in the water, allowing them to remain active year-round in Missouri’s varied climate. They are graceful, powerful swimmers and can remain submerged for 3-4 minutes. Their elongated body, webbed feet, and powerful tapered tail allow otters to swim at least half a mile while submerged.

Complex Social Lives and Breeding Success

Missouri’s otters proved remarkably successful at reproduction, contributing to their rapid population growth. Females typically give birth to 2-5 young, usually in February or March, with the young weaned at 4 months of age but staying with their parents until the following spring. Otters are relatively long-lived, still breeding into their teens in captivity and may live to be 20-25 years old. Except for raising litters, otters seem constantly on the move from place to place, not defending territories from other otters, with overlapping territories occurring often. They are social creatures, generally living in family groups and vocalizing to each other through various sounds including chirps, grunts, and snarls. This social flexibility helped them establish successful breeding populations across Missouri’s diverse waterways.

Dietary Flexibility Drives Success

One key to the otter’s successful reestablishment in Missouri was their adaptable diet. During winter months, fish occurred in 86% of their diet, while during summer, fish occurrence dropped to approximately 15% as they switched to other prey. River otters primarily eat crayfish from April through October, but during winter months when fish populations are vulnerable, otters prefer to eat fish. Otters have a high metabolic rate, with food passing through their entire digestive system in about an hour, and they eat small fish whole. They eat between 2 and 3 pounds of fish per day, making them incredibly efficient predators in Missouri’s aquatic ecosystems.

A Model for Conservation Success Worldwide

Missouri’s otter reintroduction has become a template for wildlife restoration projects across North America. The Missouri framework was extremely successful and eventually served as a template for many states, including Ohio, Kentucky, and Illinois. More than two dozen states recognized the ecological role of the river otter and launched similar restoration efforts. Federal excise taxes paid by manufacturers of firearms, ammunition, and archery gear have funded wildlife conservation, creating a model of conservation success with river otters now found in all of the contiguous United States and Alaska. Only one of the world’s 13 otter species, the North American river otter, is bucking the declining trend, leading conservation experts to call it “a conservation success story”. Missouri’s river otter saga represents more than just numbers – it’s proof that with scientific planning, adequate funding, and community cooperation, even species on the brink of extinction can make remarkable comebacks. Thanks to these efforts and improvements in stream conditions, otters are once again found throughout most of Missouri. The sight of a playful otter family splashing in a Missouri stream reminds us that nature’s resilience, combined with human determination, can achieve the seemingly impossible. What started as a desperate conservation gamble has become one of North America’s greatest wildlife success stories, proving that sometimes taking bold action pays off beyond our wildest dreams.

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.