Tim Friede still remembers the searing pain, the burning, the swelling, the moments when his vision blurred and his body fought to stay conscious. But this wasn’t an accident. He had chosen to be bitten not once, but 202 times by some of the deadliest snakes on Earth. From black mambas to rattlesnakes, Friede turned his body into a living laboratory, injecting himself with venom for nearly two decades in a quest to build immunity. Now, his blood may hold the key to a revolutionary universal antivenom, one that could save thousands of lives each year.

A Dangerous Experiment: Self-Immunization Against Snake Venom

Friede’s journey began in the early 2000s, inspired by the concept of “mithridatism” the gradual self-administration of poison to build resistance. He started with tiny, controlled doses of venom, increasing them over time. His body adapted, producing antibodies capable of neutralizing toxins that would kill most people.

But theory and reality collided in 2011, when two cobra bites in quick succession nearly killed him. “It felt like my arm was on fire,” Friede recalls. He was airlifted to a hospital, where he spent four days in a coma. Critics called him reckless, but Friede insists his work had a purpose: “If my suffering can help others, it’s worth it.”

From Blood to Breakthrough: The Science Behind a Universal Antivenom

Immunologist Jacob Glanville made an unusual request in 2021: “Can we study your blood?” Agreeing immediately, Friede had long hoped his experiments would result in medical advances.

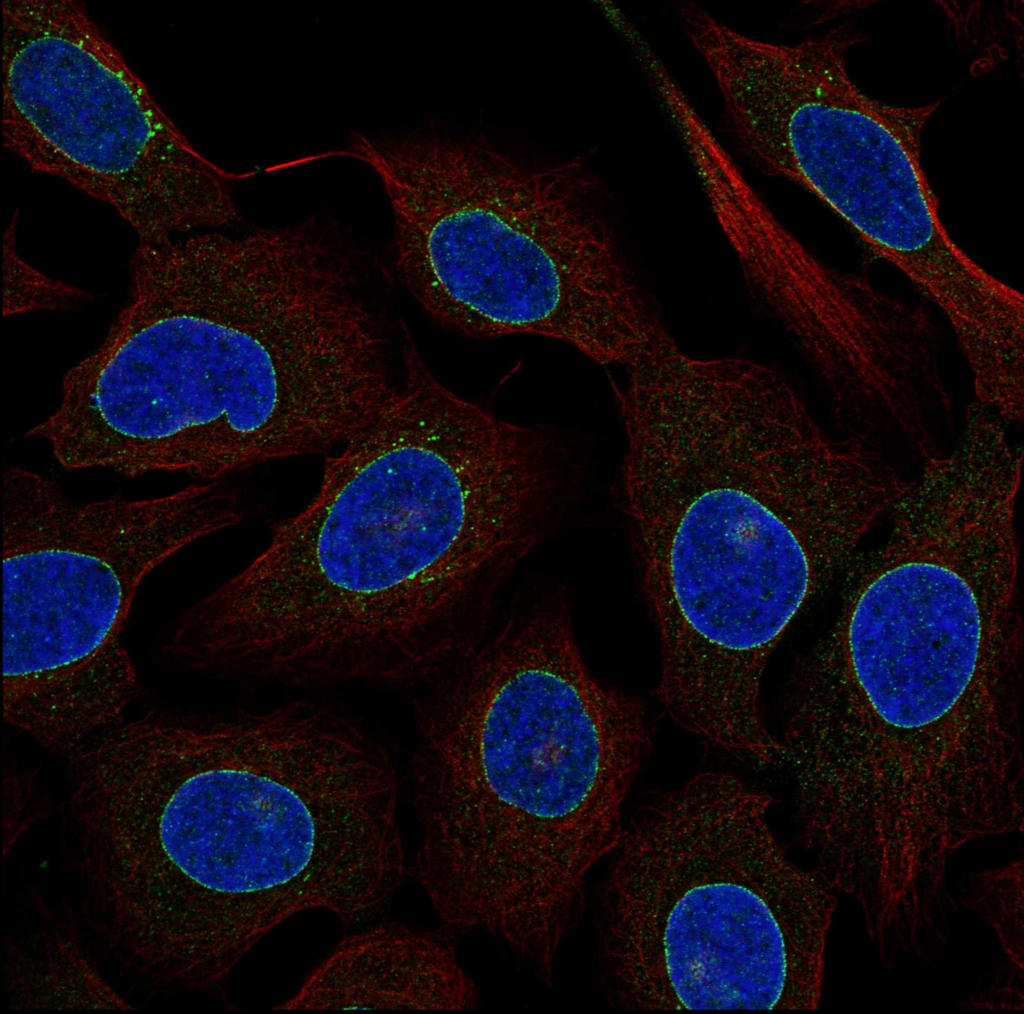

Friede’s blood included billions of distinct antibodies, some of which could neutralize venom from several snake species, according to Glanville’s team at Centivax. Their broad-spectrum antivenom was produced by separating these antibodies and combining them with an experimental drug (varespladib). In lab tests, it partially neutralized six more and completely shielded mice from thirteen different snake venums.

Why Current Antivenoms Are Failing And How Friede’s Blood Could Fix It

Traditional antivenoms are species-specific, meaning a bite from an Indian cobra requires a different treatment than one from a rattlesnake. Producing them is also slow and expensive, involving milking venom and injecting it into horses or sheep to harvest antibodies.

Friede’s approach is different. His antibodies are human-derived, reducing allergic risks. Even more groundbreaking? They target multiple venom families at once. “This could be the first step toward a true universal antivenom,” says Andreas Laustsen-Kiel, a leading venom researcher.

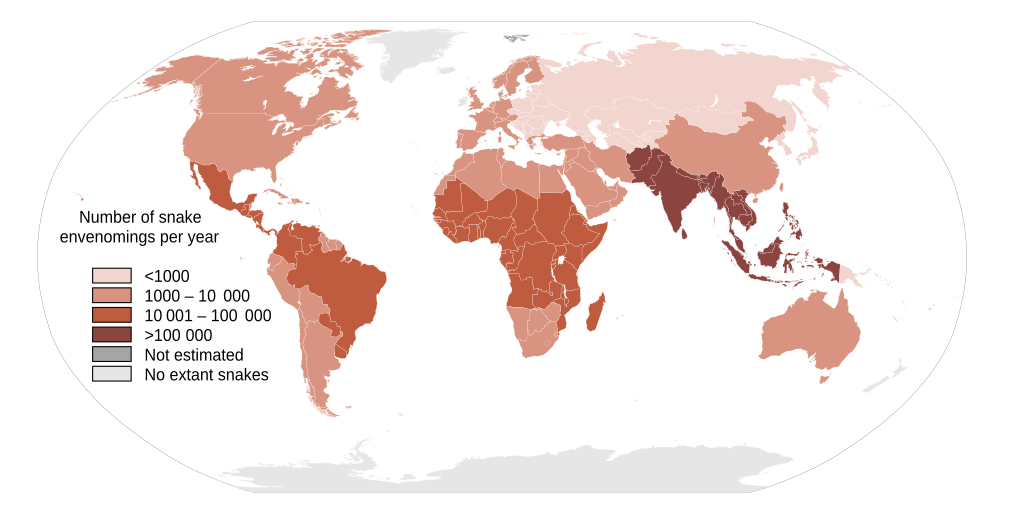

The Global Snakebite Crisis: 140,000 Deaths a Year

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that, mostly in rural areas of Africa, Asia, and South America, snake bites kill up to 140,000 people yearly. Additional 400,000 survivors have permanent disabilities including organ damage or amputations.

Because of cost and storage issues, current antivenoms are sometimes not readily available in these areas. Particularly for those who cannot get to a hospital in time, a single, heat-stable, universal antivenom could revolutionize treatment.

The Ethical Dilemma: Should Anyone Else Try This?

Friede’s methods were extremely risky. Even he admits: “I got lucky.” His kidneys and liver could have failed; his immune system might have turned against him. Glanville warns: “No one should ever attempt this.”

Instead, scientists are now using synthetic biology and AI to replicate Friede’s antibodies without needing more human volunteers. The goal? A safe, lab-made version of his immunity.

What’s Next? Testing in Dogs And Maybe Humans

The next phase involves veterinary trials in Australia, where snakebites are a major threat to dogs. If successful, human trials could follow. Meanwhile, Friede now retired from venom experiments, remains a vocal advocate for better snakebite treatments.

“People call me crazy,” he says. “But if my blood saves even one life, every bite was worth it.”

Final Thought: A Medical Revolution Born From Extreme Sacrifice

The narrative of Tim Friede is equal parts brilliance and craziness, a self-experiment that might redefine venom medicine. Although his approaches were unconventional, the science his techniques revealed could one day make snakebite deaths extinct.

Researchers are hurrying right now to turn his blood into a cure. And should they be successful, Friede’s suffering will have bestowed upon the planet a remarkable gift: immunity bottled.

Sources:

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.