High in the limestone of France’s Dordogne, a hidden gallery froze a moment in human imagination and kept it sealed for roughly seventeen thousand years. When local teenagers stumbled on Lascaux in 1940, they opened not just a cave but a vault of ancient minds at work. Since then, Lascaux has become a scientific tightrope: reveal its secrets, but do no harm. Today’s researchers move with lab-like caution, using light, air, and time as carefully as any scalpel. The mystery is still alive, and the race to understand it without destroying it is shaping how we study the deep past.

The Hidden Clues

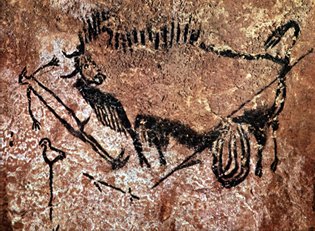

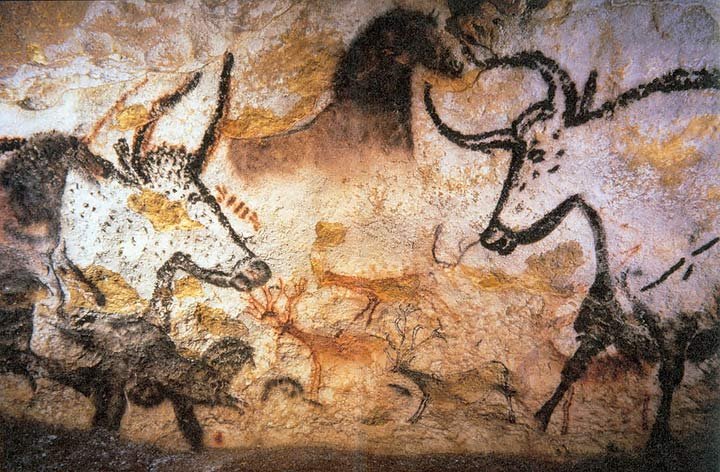

Imagine stepping into a midnight cathedral where the walls breathe with animals in motion. In the Hall of Bulls, massive aurochs charge across pale rock, flanked by powerful horses, deer, and enigmatic signs that still spark debate. Painters placed figures to ride the cave’s curves, using bumps and hollows to suggest muscle and speed, as if the stone itself joined the performance. Pigments came from the earth – iron oxides for reds and yellows, manganese minerals and charcoal for blacks – ground, mixed, and blown or brushed to create soft edges and depth. Some shapes overlap, hinting at sequences of painting and revisiting across years or generations. Even the tiniest details – sprayed dots, delicate outlines, and negative hand stencils – read like fingerprints from the Ice Age.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Archaeologists now parse these images with technologies barely imaginable a generation ago. Portable X‑ray fluorescence helps identify mineral signatures in pigments without shaving off samples, while Raman spectroscopy reads molecular structures to separate red ochres from hematite-rich blends. High-resolution photogrammetry and laser scanning stitch millions of data points into a precise 3D twin, letting researchers “walk” the cave virtually and study brushwork at sub‑millimeter scale. Because many paintings lack organic binders, direct radiocarbon dating is tricky, so teams cross‑check stylistic evidence with dates from nearby hearths and tools. Environmental loggers track carbon dioxide, humidity, and temperature, building models that predict when even a small shift could stress the walls. The result is a layered biography of the cave, where every line sits inside a changing climate of rock, air, water, and people.

- Noninvasive mapping tools reduce contact while boosting resolution.

- 3D models allow pigment, crack, and microfilm tracking over time.

- Integrated sensors flag risky spikes in humidity and CO₂ before damage happens.

The Hall of Bulls, Up Close

Stand under the high vaults and the scale hits first – these paintings weren’t casual doodles; they required planning, scaffolding, and teamwork. The artists used a kind of twisted perspective, showing horns from the front while bodies turn in profile, a visual trick to capture what the eye knows rather than what it sees. Some contours are softened with sprayed pigment, a technique that lends fur and flesh a lifelike gradient in dim light. Torches would have set the animals flickering, so movement feels baked into the design, like an early form of animation. You can trace moments of revision where a new stroke corrects an old outline, suggesting careful decision-making, not random improvisation. It’s a workshop of ideas, not a cave of accidents.

The Living Threat

Lascaux’s greatest danger isn’t vandals or floods – it’s life itself. After mid‑twentieth‑century tourism brought heat, moisture, and breath into a delicate microclimate, fungi and bacteria found a foothold and spread across the walls. Conservators have since battled outbreaks and stains, stabilizing the site with stricter access, better ventilation, and constant monitoring. Every step is recalibrated: even a technician’s body heat can tilt a local humidity curve if they linger too long. The cave is now a patient under long-term care, with protocols designed to prevent the next microbial bloom. Hard lessons from earlier interventions now drive a conservation-first mindset that favors prevention over cure.

Why It Matters

Lascaux is not just about beauty; it’s about the origins of symbolic thinking and the social glue of shared stories. Here is a culture investing long hours, scarce resources, and real risk to make images in the dark, which tells us art wasn’t decoration – it was infrastructure for memory and meaning. Traditional archaeological finds – stone points, bones, hearths – show survival; painted caves show intention, imagination, and teaching across generations. By comparing Lascaux with other Ice Age sites, researchers piece together how humans organized knowledge before writing, including what animals were valued, feared, or mythologized. The art also sits within a changing Ice Age climate, hinting at how people read seasons, migrations, and landscapes in ways that merged observation with belief. In short, Lascaux anchors a bigger narrative about how minds became modern.

Global Perspectives

Seen alongside Chauvet in France, Altamira in Spain, and far-flung rock art in Indonesia, Lascaux belongs to a global conversation about very old ideas traveling through time. Each site preserves a different moment and style, yet they share a surprising sophistication in composition and technique. Management strategies now cross borders: limited access, detailed environmental baselines, and highly faithful replicas reduce pressure on fragile originals. The Vézère Valley’s decorated caves – Lascaux among them – are recognized for exceptional universal value, which brings both attention and responsibility. Visitors learn to see a replica not as a fake, but as a protective lens that keeps the original intact. This shift in mindset may be one of Lascaux’s quietest but most important exports.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science, Part II: What We’ve Learned

Technical studies have clarified how the artists mixed pigments, layered images, and exploited the cave’s contours to create motion and depth. Microscopic residues suggest repeated visits and reworking, echoing a community practice rather than a one-off event. Scans reveal hairline cracks and salt blooms early, allowing conservators to intervene before damage blooms into a visible wound. Side-by-side spectral maps differentiate subtle blacks – charcoal versus manganese-rich mineral – pointing to choices that were aesthetic as much as practical. Even the distribution of soot and calcite films becomes data about torch routes and air flow patterns through the chambers. Piece by piece, the cave shifts from a gallery of mysteries to a dataset of behaviors.

The Future Landscape

The next wave is about listening to the cave with new senses. Environmental DNA from dust could track microbial communities without swabbing the walls, and machine learning can flag tiny pigment shifts across thousands of high‑res images. Hyperspectral imaging will map varnish-thin films and salts that a human eye can’t see, while digital twins let teams rehearse interventions in virtual space before touching stone. Climate volatility adds urgency: warmer, wetter spells can push humidity beyond safe bounds, challenging today’s ventilation strategies. Ethical debates are sharpening as well – biocide use, even in tiny doses, can ripple through a cave’s microbiome for years. The long game is a protective envelope of prediction, detection, and restraint that keeps art, rock, and microbes in balance.

Conclusion

Most of us can help by choosing the replica over the original and celebrating accuracy as a form of care. If you travel to Dordogne, the International Center for Cave Art in Montignac‑Lascaux offers a remarkably precise reconstruction, immersive light control, and rich context without the risks of body heat and breath. Teachers and parents can tap museum digital archives and 3D tours to bring cave art into classrooms, turning curiosity into stewardship early. Support organizations that fund noninvasive conservation, and be skeptical of sensational claims that encourage risky access. Share the idea that preservation isn’t about saying no; it’s about saying yes to the next century of study and wonder. The cave waited thousands of years for us – meeting it halfway is the least we can do.

Sources:

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Prehistoric Sites and Decorated Caves of the Vézère Valley.

- Centre International d’Art Pariétal Lascaux (Lascaux IV), Montignac‑Lascaux, France.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.