A Long-Standing Puzzle in Planet Formation (Image Credits: Upload.wikimedia.org)

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope recently captured observations that shed light on the elusive process behind the birth of gas giant exoplanets.[1]

A Long-Standing Puzzle in Planet Formation

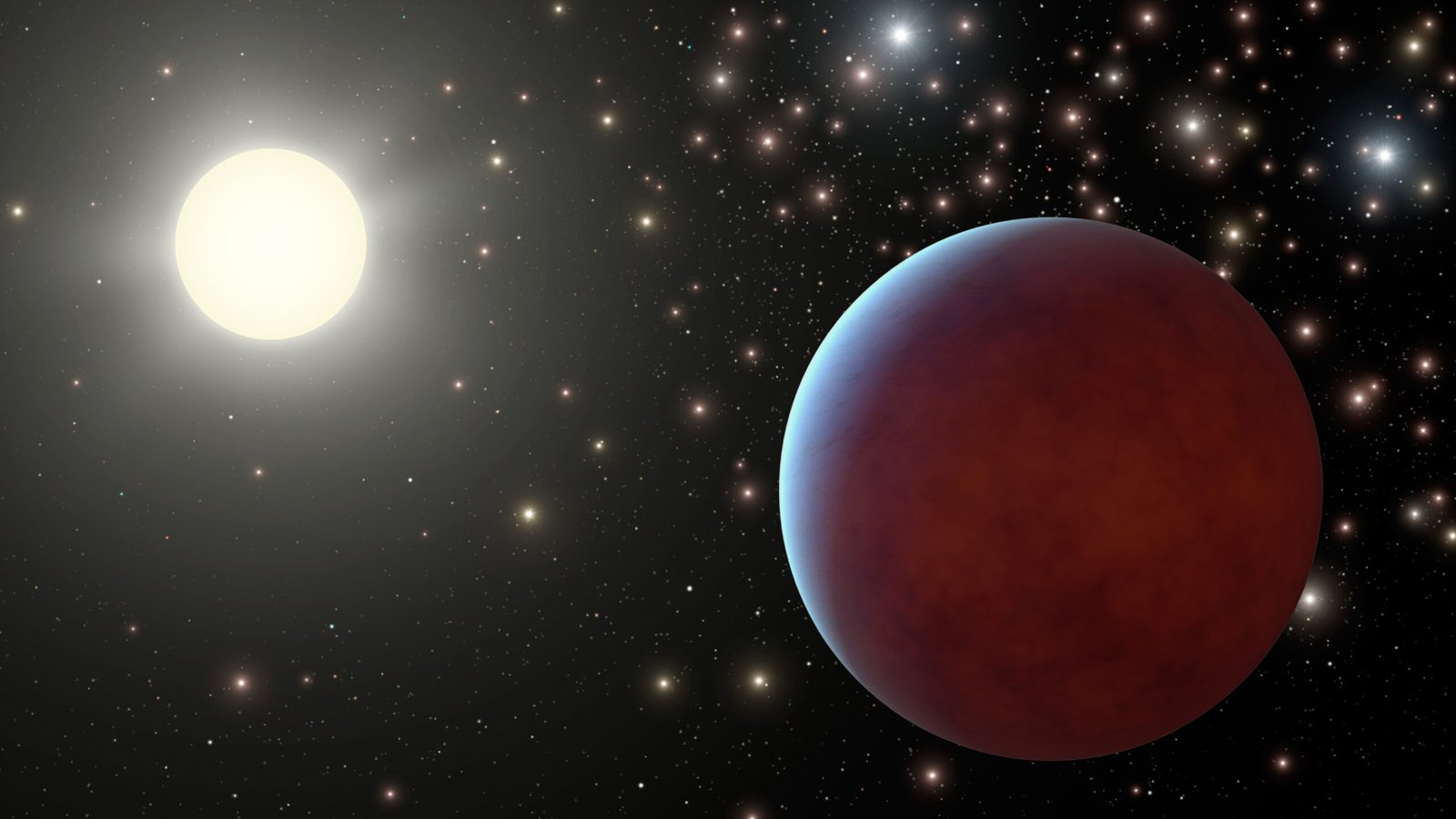

Astronomers debated two primary mechanisms for gas giant formation for decades. The core accretion model posits that a solid core of rock and ice accumulates dust and gas from the protoplanetary disk surrounding a young star. Once this core reaches about 10 times Earth’s mass, it rapidly pulls in a massive envelope of hydrogen and helium.

This process demands specific conditions, such as sufficient disk density and time before the disk dissipates. In contrast, the gravitational instability theory suggests that dense regions in the disk collapse under their own gravity, much like stars form, creating planets in mere thousands of years.[1]

Recent JWST data tips the scales toward one explanation through detailed views of protoplanetary disks.

Probing Protoplanetary Disks with Infrared Precision

The James Webb Space Telescope excels at peering into the infrared glow of warm dust and gas around newborn stars. Its instruments, including NIRCam and MIRI, detect structures invisible to previous telescopes.

Scientists targeted several young star systems hosting protoplanetary disks ripe for planet formation. These observations revealed intricate rings, gaps, and spirals – hallmarks of emerging planets sculpting their surroundings.[1]

- Rings of cooler dust indicating pressure bumps where pebbles accumulate.

- Gaps cleared by growing planet cores.

- Spiral arms suggesting gravitational tugs from massive companions.

- Warm mid-infrared emissions from gas at temperatures ideal for core growth.

Evidence Favoring Core Accretion

The new images show pebble-sized grains clumping in disk regions where temperatures allow ice to trap volatiles. This supports core accretion, as these building blocks feed rocky cores.

Moreover, detections of carbon monoxide and water vapor trace gas flows onto potential cores. Such chemistry aligns with models where cores reach runaway gas accretion before the disk’s lifetime ends, typically a few million years.

Gravitational instability appears less likely in these closer-in disk zones, where instabilities form farther out. JWST’s resolution distinguishes these scenarios by mapping temperature gradients and composition.[1]

Implications for Our Solar System and Beyond

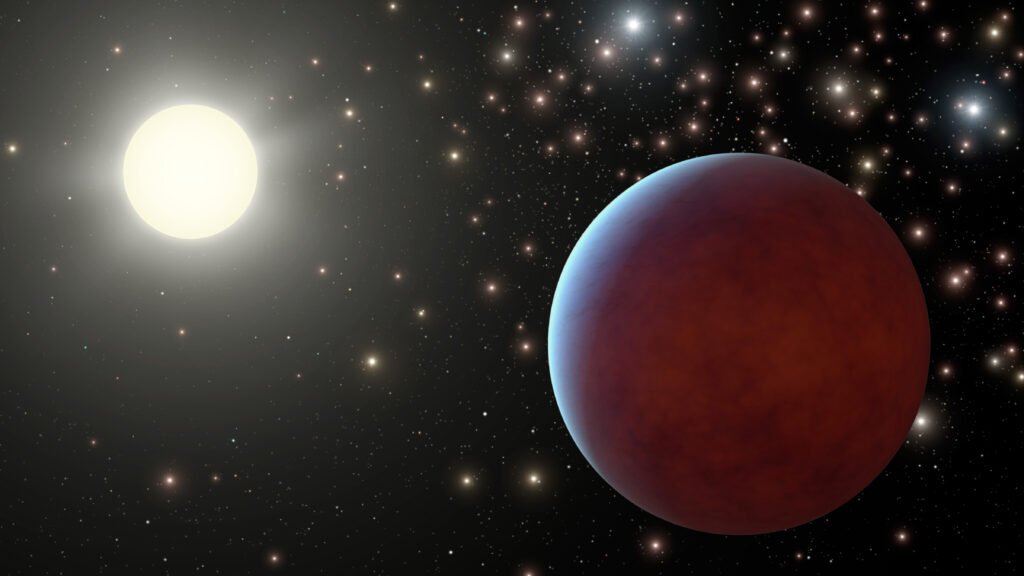

These findings mirror Jupiter’s formation timeline in our solar system, inferred from meteorites and disk models. They explain “hot Jupiters” – gas giants orbiting close to their stars – via migration after formation.

Future observations will target more disks to test universality across stellar masses and metallicities. Understanding gas giant births refines predictions for habitable zones, as these planets influence smaller rocky worlds.

| Theory | Timescale | Best Location |

|---|---|---|

| Core Accretion | Million years | Inner/Moderate disk |

| Gravitational Instability | Thousands of years | Outer disk |

Key Takeaways:

- JWST observations highlight pebble accretion fueling core growth.

- Disk structures reveal active planet sculpting in real time.

- Results bolster core accretion for most observed gas giants.

As JWST continues to map these nurseries, the story of gas giant origins grows clearer, reshaping our view of planetary systems galaxy-wide. What surprises might the next images bring? Share your thoughts in the comments.