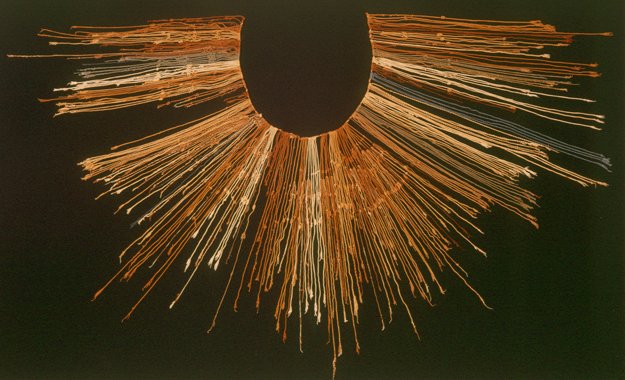

In a remote village high in the Peruvian Andes, there is a 68-meter-long (224-foot) knotted cord that is the biggest of its kind ever found. Khipus were the Inca Empire’s advanced way of keeping records. They encoded everything from tax records to poetry. But researchers now think they might have something even more amazing: a climate archive that is 500 years old.

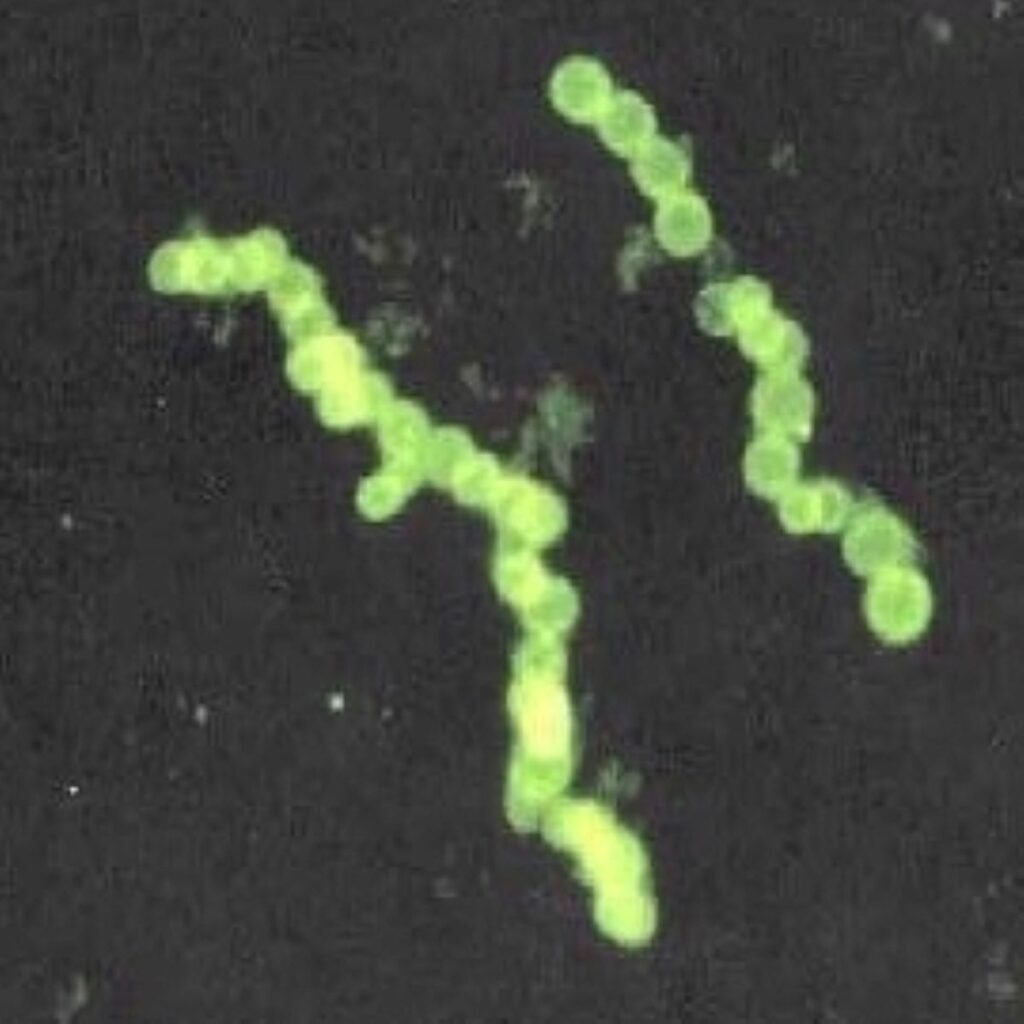

Anthropologists have found khipus in the village of Santa Leonor de Jucul that villagers used to keep track of droughts, floods, and ritual offerings to mountain spirits. These cords are different from regular khipus because they use complicated tassels, fluffy llama tails, coca pouches, and even cigarettes to keep track of changes in the environment. If we could figure out what they meant, they might be the first climate record of the Andes made by Indigenous people. They would show how ancient communities dealt with changing weather.

The Inca’s “Living” Climate Database

For hundreds of years, Andean elders used khipus as public records, just like meteorologists use satellite data today. Anthropologist Sabine Hyland, who led the research in Jucul, says, “They were looking at these as a record of the climate, trying to understand patterns just like we do today.”

The Inca system was very spiritual, while Western climate models use tools. For example, a fuzzy llama-tail tassel stood for rain clouds and was used to mark offerings to Paccha-cocha, a holy lake that was thought to control rain. When there were more tassels in a year, it meant there was a bad drought, and the villagers begged for rain. People thought that rituals for the dead that had different tassels would stop floods.

A Code Hidden in Tassels, Not Knots

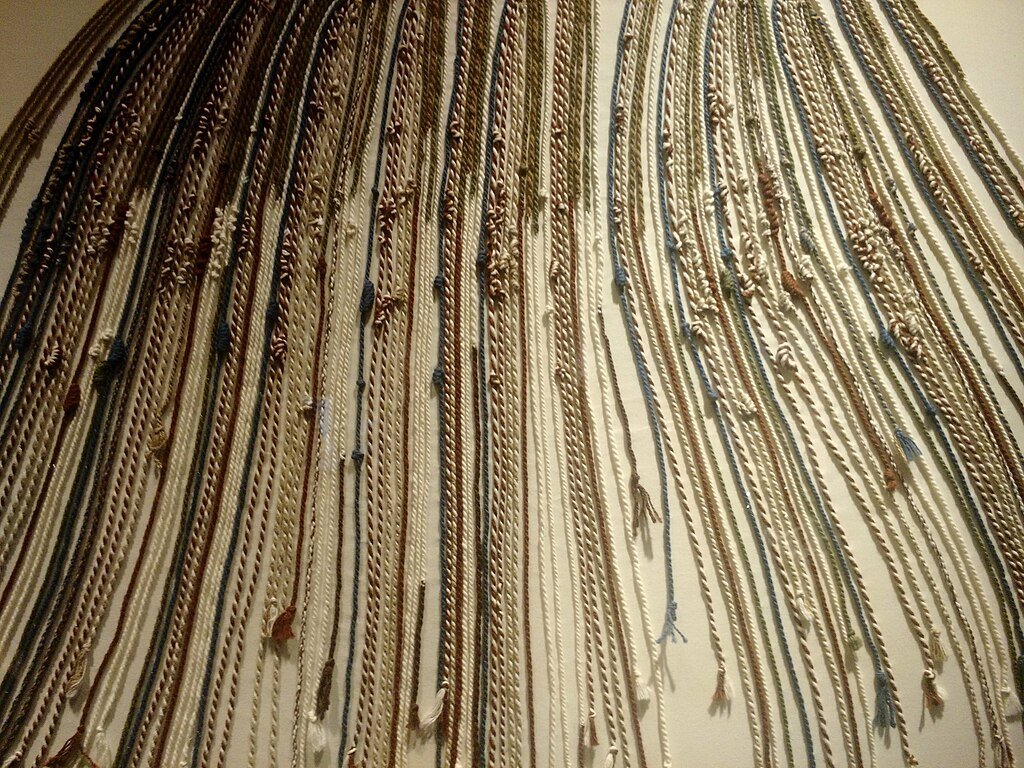

Most khipus that are still around use knots to write down numbers in a decimal manner that is like an old spreadsheet. But the Jucul cords don’t work the way we assumed they would. Instead of tying knots, they converse to one other through

- Tassels on llama tails that demonstrate how to pray for rain

- Pouches of pink coca leaves (to keep track of gifts)

- Cigarettes with doll parts (maybe to stand for gods)

Llama tails look like rain clouds, says Don Lenin Margarito, an expert on Jucul rituals. “There were a lot of Paccha-cocha offerings this year, which means it was a dry year.” This touch-based “language” shows that khipus were more than just instruments for operating things; they were also spiritual items that were part of the Andes’ spiritual ecology.

Radiocarbon Dating Could Reveal a Lost Climate Timeline

What do you need to get this data? Exact radiocarbon dating. A group of researchers led by Ivan Ghezzi is now looking at the Jucul khipus to figure out when climate events happened. If it works, it could combine traditional knowledge with modern climatology to give us new information about:

- Drought cycles from the past and how they compare to those of today

- Effects of the Little Ice Age (a time when it got colder from the 16th to the 19th centuries)

- Flood patterns before colonisation

The British Museum has paid for preservation work because the cords are in danger from insects, mould, and rodents.

Why This Discovery Challenges Western Science

Ice cores and tree rings are often used to study the climate of the West. The khipus, on the other hand, encodes how people react to environmental stress by combining weather with mythology. For instance:

- Offerings = Proxy Data: More rituals at places that bring rain, like Paccha-cocha, mean longer droughts.

- Colour and texture are important. For example, crimson cords might mean an emergency, while beige cords might mean stability.

Hyland says, “This isn’t just data; it’s a conversation with nature.” Khipus shows how communities felt about climate change, unlike sterile numbers.

The Race to Decipher a Dying Tradition

There are only five Andean villages that still protect their ancestral khipus. Knowledge fades with each elder who dies. But there are signs of progress:

- AI Analysis: Algorithms are finding patterns in the order of knots.

- Phonetic Clues: Some khipus might have Quechua syllables written on them.

Hyland’s team hopes that the Jucul cords will be the key to understanding khipu, showing how climate affected one of history’s greatest empires and how its people fought back.

What This Means for Modern Climate Science

If you could read the khipus, they could:

- Fill in the blanks in climate models by giving them data from before the colonisation of the Andes.

- Show off Indigenous Resilience: Show how old cultures changed to fit new situations.

- Change the definition of “writing”: Showing that complicated communication doesn’t need an alphabet.

Hyland says, “These aren’t just knots; they’re the voices of people who saw the clouds, felt the droughts, and tied their hopes into strings.”

Conclusion: A Thread Connecting Past and Future

The Jucul khipus are more than just old things; they show how smart Indigenous people were. Their message is important right now because of the climate crisis: To know what will happen in the future, we must listen to what has happened in the past. And sometimes the past talks in tangled cords and whispered rituals that need to be untangled.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.