A walk through a Vermont forest is like stepping into a living, breathing mystery. Sunlight flickers through ancient maple leaves, the air is thick with the scent of moss, and the ground beneath your feet hums with life you can’t see. But what if I told you the trees themselves might be whispering, sharing secrets, or even “spying” on each other—not through rustling leaves, but with the help of a hidden network of fungi beneath the soil? It sounds like something out of a fantasy novel, yet science suggests the forests of Vermont are alive with invisible conversations, all thanks to a tangled web of fungal threads that connect tree to tree. Get ready to meet the most overlooked spies in the natural world and discover how Vermont’s quiet woods are buzzing with underground intrigue.

The Mysterious Wood Wide Web

Beneath the soft carpet of fallen leaves and pine needles, a vast, intricate web stretches for miles. Scientists call it the “mycorrhizal network,” but it’s often nicknamed the “Wood Wide Web.” Imagine a city’s subway system—only instead of trains and tunnels, it’s made of fine, thread-like fungal filaments called hyphae. These mycorrhizal fungi form intimate partnerships with tree roots, weaving together the lives of different plants. The network is so dense that a single teaspoon of forest soil can contain miles of these tiny threads, connecting the roots of maples, birches, and pines in a secret underground society.

How Trees and Fungi Became Partners

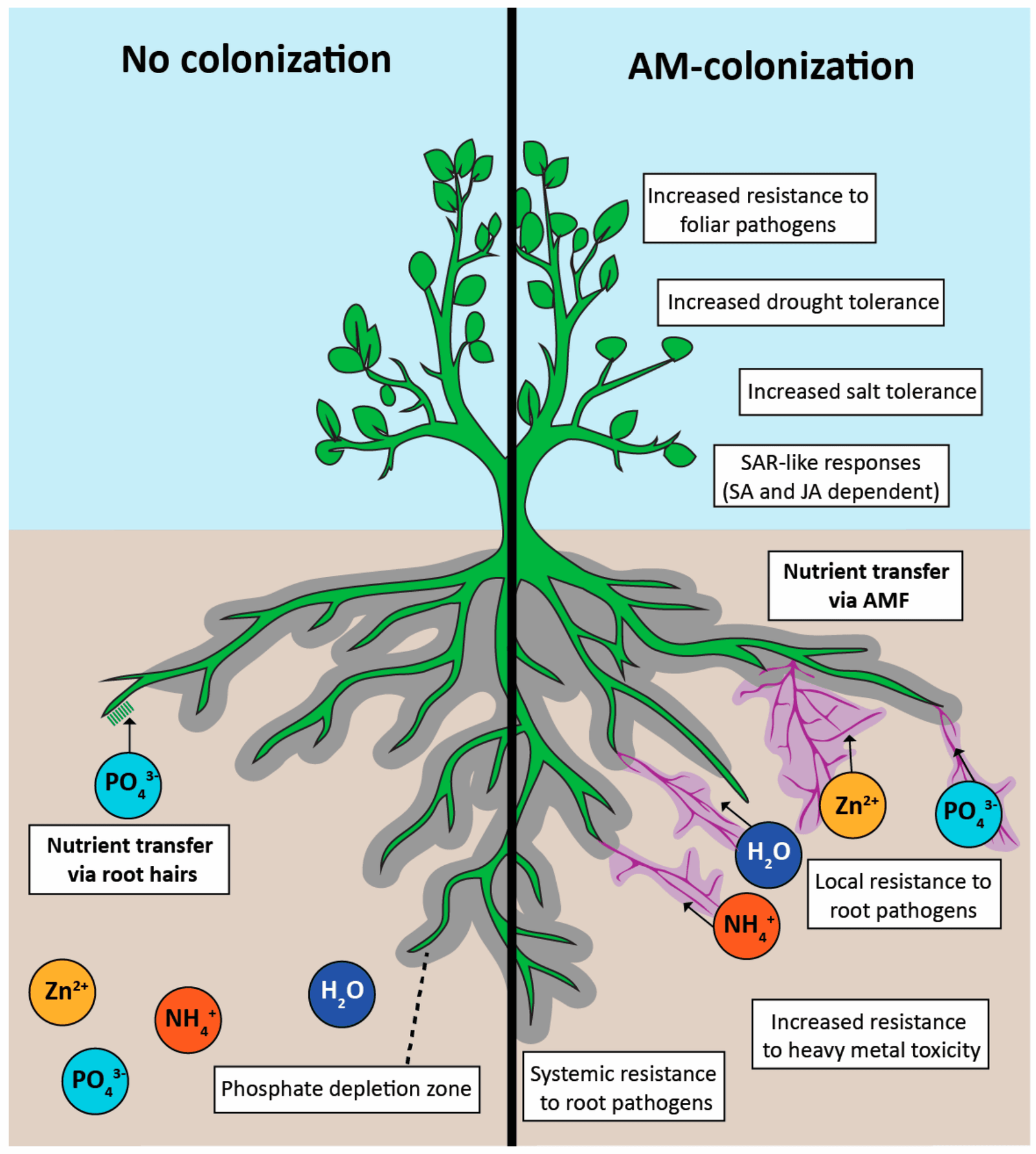

The relationship between Vermont’s trees and fungi isn’t just casual—it’s an ancient alliance that dates back millions of years. Fungi help trees absorb water and nutrients, like phosphorus and nitrogen, by extending the reach of their roots. In return, the trees feed the fungi sugars they make through photosynthesis. This partnership is so close that some trees can’t survive without their fungal allies. It’s a bond built on trust and mutual benefit, but also on constant communication—sometimes even competition.

Communication Beneath the Surface

When we think of communication, we picture birdsong or the rustle of wind. But trees have their own silent language, and fungi are the messengers. Through the mycorrhizal network, trees can send chemical signals to their neighbors. For example, if one maple is attacked by pests, it can alert surrounding trees, prompting them to boost their own defenses. These signals travel faster and farther through the fungal web than they ever could through the air or soil alone, almost like a forest-wide warning system.

The Science of Tree “Eavesdropping”

Recent research in Vermont’s forests shows that trees aren’t just passive participants—they’re active listeners. When a birch tree receives distress signals from its fungal partners, it can change its own chemistry, strengthening its leaves or producing more toxins to fend off would-be attackers. Sometimes, a tree will even “listen in” on the signals intended for another species, giving it a sneak peek at nearby threats. In this way, trees aren’t just cooperating; they’re gathering intelligence, much like spies in a Cold War drama.

The Role of Fungi as Nature’s Secret Messengers

Fungi don’t just pass along messages—they interpret, amplify, and even manipulate them. Some fungi can favor certain trees over others, channeling more nutrients and information to their preferred hosts. This makes the mycorrhizal network not just a neutral highway, but a complex, living system with its own interests and agendas. In Vermont’s wild woods, these fungal “middlemen” play both sides, shaping alliances and rivalries that ripple through the entire ecosystem.

Sharing Resources: The Forest as a Community

One of the most astonishing discoveries is how trees use the fungal web to share resources. Healthy, mature trees in Vermont sometimes send extra sugars or nutrients to younger saplings—especially if they are their own offspring. It’s a bit like parents feeding their children through an invisible umbilical cord. Even dying trees can donate their remaining resources to the network, giving nearby plants a boost before they fall. This generosity blurs the line between individual and community in the forest.

Competition and Sabotage in the Underground Network

Yet, not all is harmonious beneath the Vermont soil. Trees can use the mycorrhizal network for sabotage, sending chemical signals that inhibit the growth of rival species. In times of drought or scarcity, some trees may even hoard resources, blocking the flow to competitors. The underground web is a place of both cooperation and cunning, where alliances shift and secrets are kept.

Evidence from Vermont’s Maple Forests

Vermont’s famous maple forests are ground zero for research into these fungal networks. Scientists have found that maples connected by mycorrhizal fungi grow faster, recover more quickly from damage, and are less likely to succumb to disease. Experiments where connections are severed show a sharp decline in tree health, proving just how vital the fungal web is to the forest’s resilience. Vermont’s forests are not just collections of trees—they’re communities tied together by invisible threads.

Impacts on Forest Health and Resilience

When storms, pests, or diseases strike, the mycorrhizal network acts as a life raft for Vermont’s trees. By redistributing water and nutrients, fungi help trees survive adversity. This networked strategy makes the forest more resilient, able to bounce back from disasters that might devastate isolated individuals. In a world facing climate change and environmental stress, these underground alliances may be the key to Vermont’s forests enduring for generations.

Fungi as Forest Engineers

Fungi don’t just move nutrients and messages—they shape the very structure of Vermont’s forests. By directing resources, they can influence which trees grow tall and which struggle. Some fungal species are choosy, forming partnerships only with certain types of trees and subtly guiding the composition of the woods. In this way, the “spying” isn’t just about information—it’s about engineering the future of the forest itself.

Human Disruption: Logging and the Loss of Networks

Logging and development can break the delicate fungal networks beneath Vermont’s forests. When the soil is disturbed, the hyphae are severed, and trees lose their ability to communicate and share. This makes forests more vulnerable to disease and environmental change. Recent studies show that replanting trees alone isn’t enough; restoring fungal connections is crucial for a truly healthy, resilient woodland.

Climate Change and Shifting Alliances

As Vermont’s climate warms, fungal communities are shifting, and so are their relationships with trees. Some fungi thrive in warmer, wetter conditions, while others struggle. These changes can tip the balance between cooperation and competition, reshaping the forest in ways scientists are only beginning to understand. The future of Vermont’s forests may depend on how well trees and fungi adapt together.

Surprising Fungal Diversity in Vermont

Vermont’s forests are home to a stunning variety of mycorrhizal fungi, each with its own quirks and preferences. Some species specialize in forming networks with just one kind of tree, while others are social butterflies, connecting many species at once. This diversity creates a web of interactions as complex as any city’s social scene, with every tree and fungus playing a unique role.

Ancient Wisdom: Indigenous Knowledge of Fungal Networks

Long before scientists studied mycorrhizal networks, Indigenous peoples in Vermont understood that forests were interconnected. Traditional knowledge often emphasized the relationships between all living things, including the unseen fungi beneath the ground. Today, researchers are listening to these ancient insights, finding that science and Indigenous wisdom often point to the same truth: the forest is a living community.

Lessons from Vermont for the World

What happens in Vermont’s woods has lessons far beyond its borders. As scientists uncover the secrets of fungal networks, they’re rethinking how we manage forests everywhere. From reforestation to climate adaptation, understanding these hidden connections could change the way we protect nature around the globe. Vermont’s trees and fungi are showing the world that cooperation and communication are the keys to survival.

How Gardeners and Landowners Can Help

Anyone with a backyard or a patch of woods can support mycorrhizal networks. Avoiding chemical fertilizers and pesticides helps fungi thrive. Planting a mix of native trees and allowing leaf litter to decompose naturally nourishes the underground web. By respecting what’s beneath our feet, we become part of the forest’s secret society, nurturing the connections that keep it strong.

Fungi in Popular Culture and Imagination

From fairy tales to science fiction, fungi have always sparked our imagination. The idea of trees “spying” on each other might sound like fantasy, but it’s rooted in real, cutting-edge science. Vermont’s forests are a living reminder that the world is stranger, and more wondrous, than we often realize. The next time you wander through the woods, imagine the secret conversations happening beneath your feet.

The Future of Forest Spying: New Frontiers in Research

Scientists in Vermont and beyond are pushing the boundaries of what we know about tree-fungi communication. New technologies, like DNA sequencing and underground sensors, are revealing hidden patterns and unexpected alliances. Each discovery raises new questions: How far can these networks reach? Can we harness them to fight climate change or heal damaged forests? The research is just beginning, and the possibilities are as vast as the forest itself.

Personal Encounters: Wonder and Awe in the Woods

If you’ve ever felt a sense of awe standing in a forest, you’re not alone. Many Vermonters recall moments when the woods seemed alive with possibility—birds singing, sunlight dappling through leaves, and a sense that something more is happening just out of sight. Now, knowing that trees may be communicating through fungi, that feeling of wonder deepens. It’s as if the trees themselves are watching, listening, and caring for each other through a hidden web of life.

A Call to Curiosity

There’s still so much we don’t know about Vermont’s fungal networks and the secret lives of trees. Each step through the forest is a step into the unknown, a chance to glimpse the hidden threads that bind the world together. Will we learn to listen to the silent language of trees and fungi? The next time you find yourself among Vermont’s maples and pines, pause and imagine the underground drama unfolding all around you.