The biggest iceberg in the world, a frozen behemoth the size of Cornwall, is breaking into thousands of icy fragments close to South Georgia’s wildlife-rich coastlines. After almost four decades of drifting from Antarctica in 1986, this “megaberg” is finally giving way to warmer temperatures; its soaring cliffs are collapsing in a show both amazing and frightening. From satellite photos, one finds a surreal scene: a blizzard of ice debris fanning out across the Southern Ocean, some chunks big enough to sink ships, others dissolving into nutrient-rich meltwater possibly altering the marine ecosystem.

For researchers, sailors, and the island’s vulnerable penguin colonies, A23a’s collapse is a high-stakes natural experiment. Will it cause anarchy by blocking important penguin and seal feeding paths? Alternatively could its meltwater enrich the ocean and cause a plankton bloom benefiting the whole food chain? The fate of the iceberg and South Georgia’s wildlife hangs precariously as the clock runs out.

The Iceberg’s Odyssey: From Frozen Prison to Drifting Colossus

The path of A23a resembles an epic tale. Born in 1986 when it calved from the Filchner Ice Shelf in Antarctica, it spent thirty years frozen on the seaflower, its base buried in shallow waters 5. It at last broke free in 2020, only to be caught once more in 2024 by a whirling ocean vortex spinning helplessly for months before escaping into the Drake Passage, the infamous “iceberg graveyard” where Antarctic giants go to die.

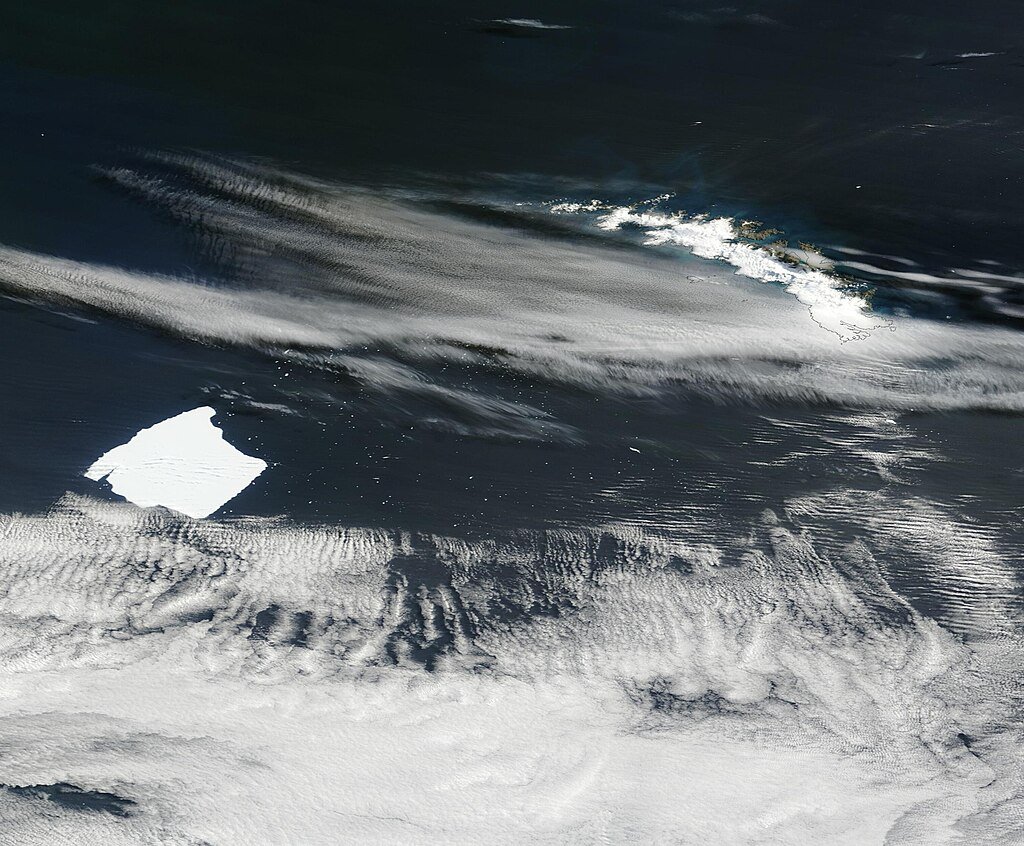

By March 2025, it grounded just 60 miles (100 km) off South Georgia, its sheer mass nearly a trillion tons halting its northward march. Now, NASA’s Aqua satellite captures its dramatic decay: “Thousands of iceberg pieces litter the ocean surface near the main berg, creating a scene reminiscent of a dark starry night”. The largest fragment, A23c, spans 50 square miles (130 sq km), while the main berg has shed 200 square miles (520 sq km) since March, a process scientists call “edge wasting”.

Wildlife on the Brink: A Repeat of Past Disasters?

Comprising over 2 million penguins and 5 million seals, South Georgia is a remote British territory hotspot for biodiversity. For some animals, A23a’s existence could be disastrous. Iceberg A38 grounded close in 2004, cutting off access to feeding areas and leaving dead penguin chicks and seal pups all over beaches.

“If the iceberg parks there, it’ll either block where they feed, or they’ll have to go around it,” warns Andrew Meijers of the British Antarctic Survey. “That burns a huge amount of energy, so less food reaches pups and chicks”. Compounding the crisis, South Georgia’s wildlife is already battling a devastating bird flu outbreak, making A23a’s disruption a potential death knell for vulnerable colonies.

Yet there’s a twist: some researchers argue the iceberg’s meltwater could seed the ocean with iron and nutrients, fueling phytoplankton blooms that feed krill the linchpin of the Southern Ocean’s food web.

The “Iceberg Alley” Menace: A Growing Threat

Sitting in “Iceberg Alley,” a path where Antarctic currents channel floating ice northward, South Georgia is But the area is experiencing more frequent megaberg invasions as climate change speeds ice loss. With its fragments lingering for months and forcing fishing vessels to negotiate a maze of ice “from the size of Wembley Stadium to desk-sized chunks,” iceberg A76 loomed dangerously near in 2023.

Sailors describe a treacherous new normal. “We have searchlights on all night to try to see if ice can come from nowhere,” says Captain Simon Wallace of the South Georgia patrol vessel Pharos 1. Meanwhile, scientists warn that as Antarctica’s ice shelves weaken, more colossal bergs like A23a will break free, turning Iceberg Alley into a high-stakes obstacle course for both wildlife and humans.

A Scientific Goldmine: What A23a Reveals About Our Planet

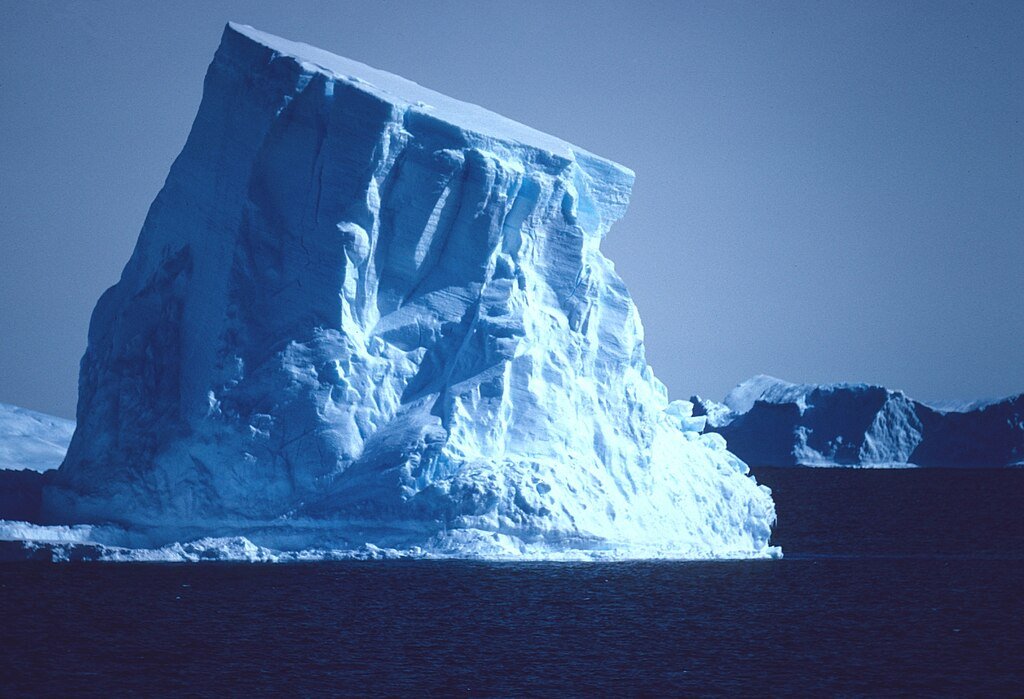

Before it vanishes, A23a has given researchers a rare opportunity. In 2023, the British Antarctic Survey’s Sir David Attenborough vessel sailed into a fissure in the berg’s walls, collecting water samples just 1,312 feet (400 m) from its cliffs. “I saw a massive wall of ice way higher than me, as far as I could see. Chunks were falling off it was quite magnificent,” recalls PhD researcher Laura Taylor.

Her team is studying how meltwater alters the Southern Ocean’s carbon cycle. As A23a dissolves, it releases trapped nutrients and phytoplankton, which may help sequester CO₂ a fleeting counterbalance to human-driven climate change.

The Climate Paradox: Natural Process or Human Accelerant?

A23a’s calving in 1986 predates the worst of modern warming, but its accelerated drift and decay align with broader Antarctic instability. Since 2000, the continent’s ice shelves have lost 6 trillion tons of mass, with melt rates six times faster than in the 1990s.

“Big berg calvings are normal, but their frequency is increasing,” says Meijers. While A23a isn’t directly caused by climate change, it’s a stark reminder of the fragility of polar ecosystems and the cascading consequences of ice loss.

Epilogue: A23a’s Legacy

A23a will linger even as it melts into oblivion. Regarding the animals of South Georgia, the stakes are existential. It is a case study for scientists on how icebergs shape oceans. For the planet as well, it portends a time when melting ice redefines coastlines, ecosystems, and even the balance of climate for Earth.

One thing is certain: A23a’s last act in the chilly Southern Ocean theater will be unforgettable.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.