A striking new study suggests that Uranus and Neptune—long classified as “ice giants”—may instead be better described as “rock giants” with cores dominated by rock rather than frozen materials. This challenges decades-old assumptions about these distant planets’ internal compositions and opens fresh questions about how giant planets form and evolve. The research, led by planetary scientists at the University of Zurich, proposes hybrid interior models that fit observational data while revealing that rock-rich cores could be just as plausible as the traditionally assumed icy ones.

If confirmed, this shift could reshape our understanding not only of our own solar system’s outer members but also of similarly sized exoplanets around other stars, which are often grouped into “ice giant” categories based on size and composition assumptions. The study highlights how much remains unknown about these worlds and underscores the need for dedicated space missions to gather more detailed measurements of their deep interiors.

Rethinking “Ice Giants” and What That Really Means

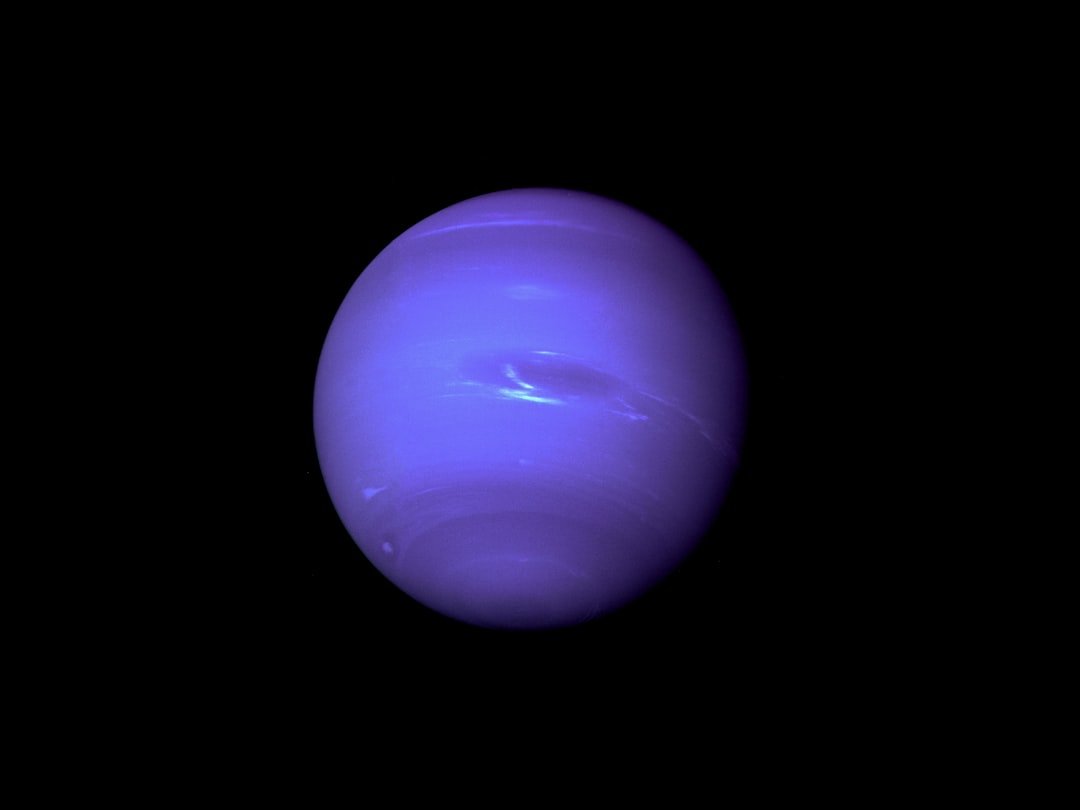

Uranus and Neptune have traditionally been labeled ice giants because they contain significant amounts of volatile compounds—like water, ammonia, and methane—that were thought to be frozen during planet formation. These ices distinguish them from the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, which are dominated by hydrogen and helium.

However, the new models suggest that this “ice” label may be misleading, as materials under the extreme pressures inside these planets behave very differently from familiar ice on Earth. At such depths, water and other volatiles may be in exotic states like super-critical fluids or ionic phases, while a much larger fraction of rock and metal may dominate the interior than previously thought.

Breakthrough Models with Hybrid Approaches

The Zurich research team developed a novel modeling technique that combines physical theory with observational constraints—balancing unbiased assumptions against real data to derive possible interior compositions. These models produced a range of possible structures for both planets, some showing rock-to-water ratios far higher than classical “ice giant” models would predict.

In this framework, rock may play a significant role in shaping the planets’ interiors, while layers of ionic water and other exotic fluids still contribute to unique behaviors like unusual magnetic fields and heat flows. Such hybrid scenarios challenge the simplistic notion of giant planets as either purely icy or purely rocky.

Magnetic Mysteries and Deep Interiors

One longstanding puzzle about Uranus and Neptune is their complex magnetic fields, which don’t resemble the simple dipole fields seen on Earth or Jupiter. The new models suggest that if layers of ionic water and rock coexist in specific configurations, these deep structural differences could naturally explain multiple magnetic poles and unexpected field orientations.

For instance, the models imply that Uranus’s field may originate closer to its center than Neptune’s, hinting at distinct interior dynamics beneath similar outer appearances. These insights could help resolve decades-old questions about why these planets’ magnetic signatures are so odd.

Limitations of Current Data and the Need for Missions

Despite their promise, the rock-giant models come with significant caveats. Key uncertainties stem from our limited understanding of material behavior under the extreme pressures and temperatures found inside these planets, as well as the sparse data available from past missions like Voyager 2.

Because of this, scientists emphasize that current observations are insufficient to definitively distinguish between “rock giant” and “ice giant” scenarios. To move beyond theory, researchers argue for dedicated future missions to Uranus and Neptune equipped to measure gravity fields, magnetic structures, and atmospheric composition in much greater detail.

Broader Impacts on Planetary Science

If Uranus and Neptune are indeed rock giants, the implications extend beyond our solar system. Many exoplanets with Neptune-like sizes have been discovered, and rethinking their internal makeup could influence how astronomers classify and model these distant worlds. A rocky interior with thick volatile envelopes might be more common than once believed, reshaping theories of planet formation and migration.

This change would prompt updates not only in textbooks but also in how future space observatories interpret observational signatures from distant planetary atmospheres and interiors.

A Wake-Up Call for Planetary Classification

The possibility that Uranus and Neptune are rock giants—not ice giants—is more than a semantic shift; it’s a profound reminder of how much we still don’t know about the worlds in our own cosmic backyard. These new models underscore that planetary classification is fluid, evolving with better data and deeper theoretical insight. By challenging decades-old assumptions, this research highlights the pitfalls of relying on labels that oversimplify complex physical realities. As we push further into the era of precision planetary science, the true nature of these enigmatic giants will remain one of the solar system’s most compelling puzzles—one that demands ambitious exploration and open minds.