Imagine stepping into a suburban neighborhood in the early 1900s—lush lawns, bursts of colorful blooms, and neat hedges lining every sidewalk. It looked like paradise, but hidden behind that beauty was a quiet invasion. Without realizing it, homeowners and landscape designers welcomed foreign plants that would forever change the balance of local ecosystems. The choices made back then still ripple through our gardens and wild spaces today, shaping the very look and health of our neighborhoods. How did these trends take root, and what lessons do they hold for us now?

The Allure of the Exotic

At the turn of the 20th century, homeowners wanted more than just grass and native shrubs. Exotic plants from far-off continents were seen as symbols of wealth, sophistication, and adventure. Nurseries were quick to import unusual flowers, vines, and trees, advertising them as must-haves for the modern garden. People delighted in unusual textures and colors, often unaware of the ecological consequences. The thrill of owning something rare trumped concerns about how these newcomers might interact with native species. In many cases, these imported plants escaped the boundaries of backyards, thriving with unexpected vigor.

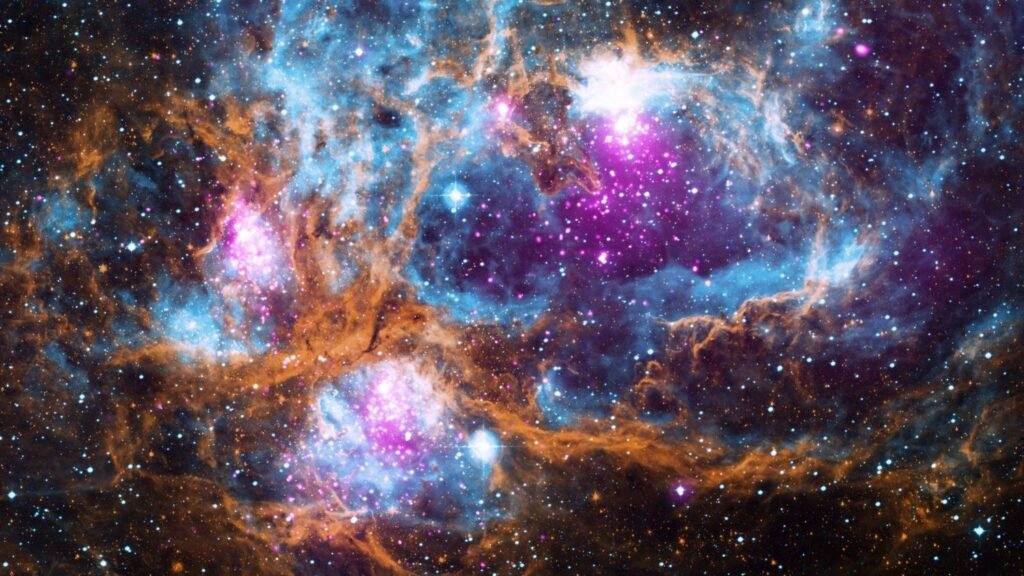

Garden Catalogs: The Trendsetters

Printed garden catalogs became wildly popular during this era, with companies like Burpee and Jackson & Perkins shaping public taste. These catalogs were more than just shopping lists—they were glossy promises of beauty and abundance. Vivid illustrations enticed readers to try Japanese honeysuckle, English ivy, and multiflora rose. Homeowners trusted these brands and rarely questioned the origins or behavior of the plants advertised. As a result, invasive species were often introduced en masse, with little thought for their adaptability or potential harm.

The Role of the Suburban Boom

After World War II, suburbs exploded in size. Developers raced to build homes, and landscaping was a major selling point. Quick-growing, hardy plants were preferred since they could green up a bare lot in no time. Many of these were non-native species that had proven resilient in other parts of the world. The speed and scale of suburban expansion meant that mistakes spread quickly—one development’s landscaping choices would be copied by others nearby. Within a generation, invasive plants had become a common sight on new streets.

Japanese Knotweed: A Cautionary Tale

Japanese knotweed is one of the most notorious examples of an invasive plant introduced for landscaping. It was first brought to North America in the late 1800s as an ornamental curiosity. By the 1900s, it was widely planted for its bamboo-like stems and hearty growth. But knotweed quickly escaped gardens, invading riverbanks and roadsides where it outcompeted native plants. Today, its aggressive underground rhizomes make it nearly impossible to eradicate, costing millions in damage control each year.

The English Ivy Epidemic

English ivy was prized for its elegance and ability to cover unsightly walls in a lush green blanket. In the shade of suburban yards, it thrived, quickly climbing trees and fences. But what started as a charming groundcover soon spiraled out of control. Ivy’s dense mats smothered native undergrowth and weakened trees, increasing the risk of storm damage. In many cities, it’s now considered a noxious weed that threatens both gardens and wild spaces.

Privet Hedges: Privacy with a Price

Every suburbanite wanted privacy, and privet hedges offered a fast, living fence. European and Asian privets grew quickly and could be shaped into perfect green walls. Yet these hedges dropped seeds that birds happily spread, resulting in untamed thickets in parks and forests. As privet crowded out native shrubs, it disrupted habitats for birds and insects, leading to a cascade of ecological changes.

Multiflora Rose: From Fence to Foe

Originally touted as a “living fence” and erosion control, multiflora rose was planted along highways and property lines. Its fragrant blooms and rose hips made it seem like a win-win. But the plant’s arching canes and prolific seed production allowed it to overrun pastures, fields, and woodlands. Today, it’s a prickly menace, forming impenetrable thickets that choke out nearly everything else.

Norway Maple: The Shady Invader

Norway maple became the street tree of choice in countless neighborhoods. Its wide canopy and tolerance for pollution made it seem perfect for city planting. Yet beneath its dense leaves, little else could grow. The tree outcompeted native maples, altered soil chemistry, and even changed the light patterns of forests. What looked like an urban blessing turned into a silent ecological shift.

Periwinkle and Groundcovers Gone Wild

Vinca, or periwinkle, was a favorite for its glossy leaves and blue flowers. Sold as a low-maintenance groundcover, it was planted in shady corners and under trees. But vinca spreads by runners, quickly marching beyond garden beds into woods and fields. Its thick mats can prevent native wildflowers from sprouting, reducing biodiversity in areas where every plant counts.

Bamboo: Fast-Growing Nightmare

Bamboo’s rapid growth and tropical appeal made it a sensation among gardeners looking for dramatic effect. Promoted as a privacy screen, it was often planted along property lines. Few realized how aggressively bamboo’s roots could travel—sometimes popping up in neighbors’ yards or even through concrete walkways. Getting rid of unwanted bamboo can be like waging a never-ending battle, with new shoots returning year after year.

Butterfly Bush: Beauty with Consequences

Butterfly bush (Buddleia) was marketed for its fragrant flowers and ability to attract pollinators. While it does draw butterflies, it also spreads easily by seed, especially in disturbed soils along roads and riverbanks. In some regions, butterfly bush now forms dense stands that crowd out native plants, ironically reducing the diversity of nectar sources for insects.

Chinese Wisteria: The Climbing Giant

Chinese wisteria’s cascades of purple flowers made it a showstopper in any garden. But it’s a vigorous climber, twisting around trees, fences, and even buildings with incredible force. Once established, wisteria can strangle trees and topple fences, its woody vines growing thicker each year. Removing mature wisteria is a Herculean effort, often requiring cutting, digging, and repeated treatments.

Ornamental Grasses: Seeds on the Wind

With their feathery plumes and low-maintenance appeal, ornamental grasses became trendy in mid-century landscapes. Some species, like pampas grass and miscanthus, produce thousands of seeds that the wind carries far and wide. Once established in natural areas, these grasses can overwhelm native plants and change fire regimes—sometimes making wildfires more intense.

The Science of Invasiveness

Why do some plants become invasive while others remain well-behaved? Scientists study traits like rapid growth, prolific seed production, and adaptability to different soils. Invasive plants often lack natural predators or diseases in their new homes, allowing them to flourish unchecked. Once established, they can alter soil chemistry, water cycles, and even the behavior of local wildlife, creating a domino effect through the ecosystem.

Ecological Costs of Aesthetic Choices

The quest for a beautiful yard or eye-catching boulevard came with hidden costs. Invasive plants reduce biodiversity, making it harder for native birds, insects, and mammals to survive. They can also increase maintenance costs for cities and homeowners, as well as decrease property values when infestations become severe. What started as a matter of taste has become a widespread ecological challenge.

The Rise of Native Plant Awareness

Today, there’s a growing movement to restore native plants in suburban landscapes. Gardeners and city planners are rethinking what beauty means, choosing wildflowers, grasses, and shrubs that support local wildlife. Native plants require less water and fertilizer, are better adapted to local soils, and help rebuild the ecological web disrupted by earlier trends. This shift is part science, part cultural change, and part coming to terms with the past.

Personal Stories of Regret and Restoration

Many homeowners have stories of regret—planting English ivy or bamboo, only to spend years battling their spread. Others share moments of joy when native wildflowers return or when butterflies flock to their restored gardens. These personal experiences highlight how deeply our choices matter, and how every backyard can become a haven for biodiversity—or a launchpad for invasion.

Lessons for Future Landscapes

Looking back, it’s clear that fashion and function both played a role in the spread of invasive plants. Today’s gardeners can learn from the past by choosing plants thoughtfully, researching their origins, and considering their long-term impact. Simple changes—like replacing a privet hedge with native elderberry or swapping out periwinkle for wild ginger—can make a world of difference. The future of our suburbs depends on the decisions we make now, one plant at a time.

The Unfinished Story of Suburban Nature

The story of invasive plants in the suburbs is still unfolding. While much damage has been done, there’s hope in the growing awareness and actions of individuals and communities. As we tend our gardens and design our neighborhoods, we’re not just shaping our own view—we’re writing the next chapter for local wildlife, water, and wildflowers. The landscape choices of today will become the legacy of tomorrow.