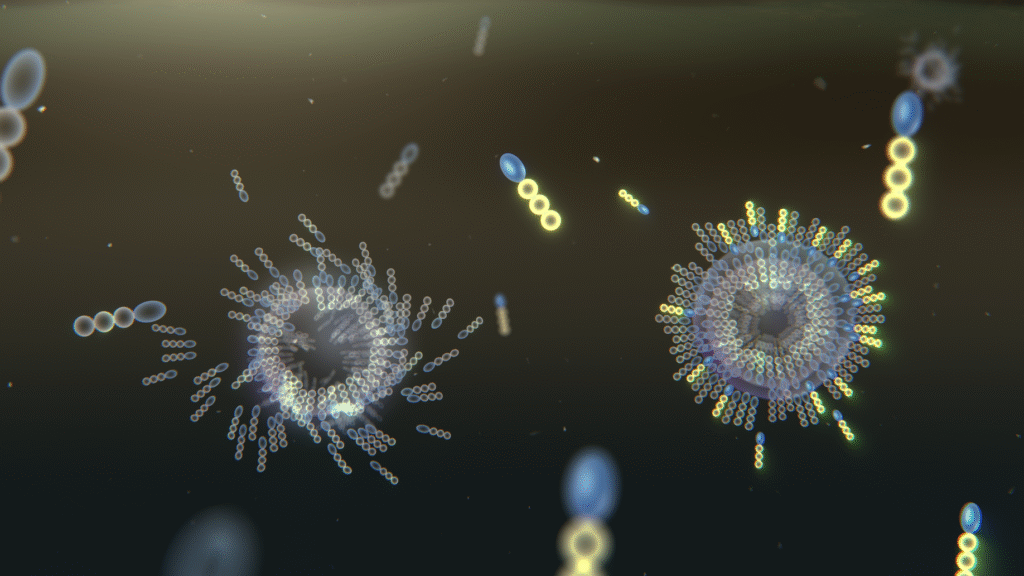

Protocells Relied on Physics Before Genes Took Over (Image Credits: Upload.wikimedia.org)

Tokyo, Japan – A recent experiment revealed how temperature swings in icy conditions propelled the growth and selection of protocells, the simple precursors to modern life.

Protocells Relied on Physics Before Genes Took Over

Modern cells depend on elaborate genetic instructions and protein machines for division and survival. Protocells, however, operated through basic physical and chemical traits of their lipid membranes. Researchers at the Earth-Life Science Institute at the Institute of Science Tokyo tested this idea by simulating early Earth environments.[1][2]

The team created large unilamellar vesicles, or LUVs, from phospholipids common in prebiotic scenarios. These vesicles mimicked protocells as they endured repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Such cycles recreated the harsh, fluctuating temperatures protocells likely faced. The study highlighted how membrane physics drove early evolutionary steps.[3]

Key Lipids and Their Physical Traits

The experiment used three phosphatidylcholine lipids: POPC, PLPC, and DOPC. Each shared a common head group but varied in fatty acid tail unsaturation. POPC featured one double bond, forming rigid membranes. PLPC and DOPC, with more double bonds, produced fluid structures.[1]

| Lipid | Structure | Membrane Property |

|---|---|---|

| POPC | One unsaturated chain (single double bond) | Rigid |

| PLPC | One unsaturated chain (two double bonds) | Fluid |

| DOPC | Two unsaturated chains (one double bond each) | Fluid |

Lead author Tatsuya Shinoda noted that these lipids linked prebiotic chemistry to modern membranes while holding internal contents effectively. Mixtures of these lipids allowed tests of compositional biases under stress.[2]

Ice Stress Sparked Fusion and Growth

After three freeze-thaw cycles, POPC-rich vesicles clustered into small aggregates. PLPC- or DOPC-rich ones fused into larger compartments. Fusion probability rose with PLPC content, favoring unsaturated lipids. Ice crystals stressed membranes, fragmenting them and prompting reorganization on thaw.[1]

Coauthor Natsumi Noda explained that looser packing in unsaturated membranes exposed hydrophobic areas. This eased fusion between vesicles, an energetically favorable process. Such merging mixed contents, concentrating organics in prebiotic soups. The setup concentrated solutes as ice expelled them into liquid channels.[3]

Retaining Genetic Cargo Under Duress

PLPC vesicles captured and held more DNA than POPC ones before cycles began. Post-thaw, PLPC retained a greater DNA fraction each time. This enriched populations with unsaturated membranes and their original genetic loads. The bias suggested early selection for protective compositions.[2]

- Unsaturated membranes promoted fusion and size increase.

- They better accumulated informational polymers like DNA.

- Ice-driven stress selected fluid over rigid structures.

- Trade-off existed: fluidity aided mixing but risked leaks.

Toward Darwinian Evolution in Icy Worlds

Senior author Tomoaki Matsuura proposed that repeated cycles enabled recursive selection. Fission via osmosis or shear could sustain protocell generations. Over time, advantageous traits spread physically before genes dominated. This bridged simple compartments to complex cells capable of full evolution.[1]

Icy sites complemented other origin scenarios like wet-dry cycles or vents. Membrane fitness varied by conditions, with no universal optimum. The findings appeared in Chemical Science.[1]

Key Takeaways

- Freeze-thaw cycles biased protocells toward unsaturated lipid membranes for growth and fusion.

- Fluid membranes retained genetic material better amid icy stress.

- Physical selection preceded genetic control, paving life’s path.

This research reframes icy environments as cradles for life’s dawn. How might such mechanisms play out on distant icy moons? Share your thoughts in the comments.