Every time you stand in front of a pyramid, a Roman aqueduct, or a megalithic stone circle, there’s this nagging feeling: how on earth did they pull this off without cranes, lasers, and heavy machinery? The stones weigh as much as trucks, the alignments are razor sharp, and the margins for error were tiny. Yet these monuments were built thousands of years ago with what, at first glance, look like sticks, stones, and guesswork.

The truth is way more fascinating than any mystical explanation. Ancient builders were not primitive at all; they were patient, systematic experimenters who understood materials, geometry, and human organization at a level that still commands respect today. Once you look closely at how they worked, the story stops being about miracles and starts being about relentless human ingenuity, cooperation, and stubbornness on a crazy long time scale.

The Hidden Power Of Simple Machines

One of the most surprising facts is that almost all ancient mega-projects can be explained with the same basic tools kids learn about in school: levers, ramps, rollers, pulleys, and sledges. A single person with a sturdy lever can move a stone that would be impossible to lift directly, by trading distance for force. Teams could raise multi‑ton blocks using wooden sleds on lubricated paths, earthen ramps, and carefully timed pulls, turning what looks impossible into something just barely achievable with enough people and patience.

Ramps, in particular, were the secret weapon behind many ancient stone projects. Instead of lifting a block straight up, you drag it along a gentle incline, which is harsh but doable with teams of workers, ropes, and maybe wet sand or mud to reduce friction. Experiments in the last few decades have shown that small crews today can move multi‑ton stones with replica tools, just by using clever combinations of rollers, sledges, and levers. When you scale that up over decades with organized labor, the physics starts to make sense.

Organized Labor: Turning People Into Heavy Machinery

What we often call “primitive tools” were supercharged by something modern people tend to underestimate: disciplined, large‑scale human labor. Ancient states could coordinate thousands of workers, sometimes seasonally, when flooding or weather made farming difficult. Instead of sitting idle, communities were funneled into building projects that served political, religious, or social purposes. The result was a kind of human-powered construction machine, built out of people rather than steel.

On these vast sites, there were planners, overseers, stone masons, haulers, cooks, and tool makers, all playing specific roles. Work was divided into repeating, trainable tasks: cut this shape, haul this distance, place this here. With clear routines, songs to keep rhythm, and social pressure or rewards, enormous groups could pull together in almost frightening coordination. It’s not romantic, but it’s very human: a mix of ambition, coercion, belief, and community pride powering projects that no single person could have even imagined completing alone.

Stonework Mastery Without Metal Monsters

Look closely at ancient stone blocks and you see the fingerprints of intense, patient craftsmanship rather than magic machines. Many cultures used stone tools, copper, bronze, and later iron chisels, paired with abrasives like sand, crushed stone, and water to shape incredibly hard materials. Instead of slicing through granite like butter, they would chip, peck, groove, and grind over and over, sometimes for days on a single surface, until the stone finally gave in. It’s slow, but over years, that slowness adds up to cathedrals of stone.

Some of the “impossibly precise” fits between blocks can be explained by a mix of good geometry and a willingness to adjust and rework. Surfaces were checked with straight edges, plumb lines, and cords, then corrected again and again until gaps became almost invisible. In some cases, builders deliberately left rough edges and then finished joints in place once the stones were already sitting together, like sculpting a puzzle after assembling it. From far away it looks like perfection at first try; up close it’s revealed as relentless trial, error, and refinement.

Geometry, Alignment, And The Math In Their Heads

Even without modern notation or calculators, ancient builders were not guessing when it came to angles, alignments, and layouts. They used ropes knotted into fixed intervals, basic right‑angle triangles, and repeated measurements to transfer precise plans onto the ground. A simple triangle with sides in fixed ratios could be recreated anywhere with a rope, giving them reliable right angles and consistent proportions. Over long distances, they used sighting poles, leveled water trenches, and repeated measurements to keep structures straight and aligned.

Alignments with the sun, stars, and cardinal directions often came from combining basic observation with patient record keeping over generations. If you watch where the sun rises on the horizon during the year and mark it carefully, patterns emerge, and those patterns can be built into architecture. The accuracy can be shocking, but it comes from time and repetition rather than magic numbers. In a way, the math was carried in their tools, their methods, and their habits, not just in written formulas.

Material Knowledge: Reading Rock, Wood, And Earth

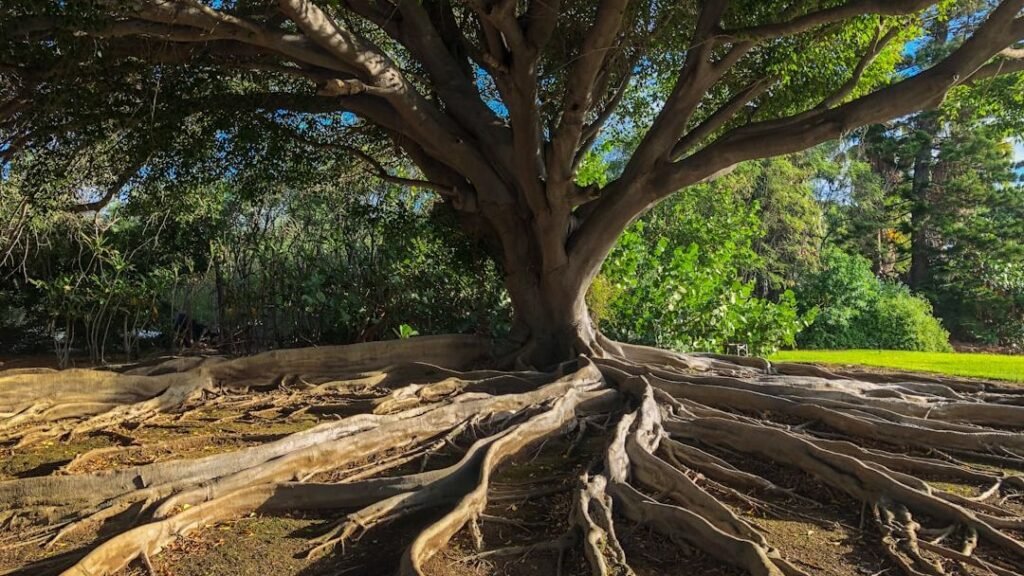

Ancient builders knew their materials intimately, the way a carpenter knows which board will split and which will bend. They learned which stones fractured cleanly, which resisted weathering, and which could be carried from far quarries without breaking apart. This knowledge came from centuries of trial and sometimes painful error, as cracked blocks, failed walls, or collapsed roofs taught harsh lessons. Over time, those lessons turned into unwritten engineering rules about thickness, span, and weight.

They also treated earth itself as a structural material. Huge platforms, embankments, and terraces were formed from compacted soil and gravel, often layered and drained so they would not slump or wash away. Wood served as scaffolding, frames, rollers, sled runners, and temporary supports, constantly being re‑used or recycled from one stage of a project to the next. What looks like stone alone was often stone resting on a carefully engineered combination of earth and timber that spread loads and kept the whole thing stable.

Time, Belief, And The Will To Build For Generations

One thing that really separates ancient mega‑projects from modern work is the sense of time. Many of these structures took decades or even generations to complete, and no one expected instant results. A person might start work on a temple knowing their grandchildren would see the finished version. That kind of long horizon changes what feels “worth it” when it comes to hauling stones and carving blocks by hand. Projects became part of the rhythm of life, not just a line item on a schedule.

Belief systems and power structures gave these efforts emotional fuel. People were not just building storage sheds; they believed they were constructing homes for their gods, monuments to their rulers, or sacred landscapes that anchored their identity. That emotional charge made unbearable labor slightly more bearable, at least for some. Whether we see that as inspiring or troubling, it explains why communities poured so much effort into stone and earth on such a massive scale.

Modern Experiments That Demystify The “Impossible”

Over the last few decades, archaeologists, engineers, and curious enthusiasts have tried to recreate ancient building methods with replica tools, and the results are eye‑opening. Teams using wooden sledges, ropes, and simple levers have successfully moved stones weighing several tons, raised pillars, and assembled small pyramids or walls. These experiments are exhausting, chaotic, and full of small failures, which oddly makes them more convincing. They show that the work is brutally hard but not outside the realm of human ability.

Experimental projects also reveal just how much coordination and planning mattered. When people pull out of sync, ropes break or stones lurch dangerously; when they move together with a clear plan, the same heavy block glides forward surprisingly smoothly. Seeing modern volunteers struggle and then adapt gives a tangible sense of what ancient crews must have gone through, day after day. It doesn’t remove the mystery so much as shift it: from “How did they do this at all?” to “How did they keep doing this for so long?”

Ingenuity Over Magic

When you peel back the layers of awe and myth, ancient mega‑structures stop looking like the work of supernatural forces and start looking like the ultimate expression of what people can do when they combine simple tools, organized labor, and stubborn determination. Levers, ramps, ropes, and chisels may not sound glamorous, but used intelligently and repeatedly over years, they can reshape entire landscapes. The real miracle is not the tools themselves but the patience, coordination, and willingness to live inside a long‑term project that might outlast your own lifetime.

Standing in front of these structures today, it’s tempting to imagine secret technologies lost to time, but in many ways, the techniques are still with us in humble forms: scaffolds on construction sites, surveyors with their tripods, workers moving things with prybars and dollies. Maybe the more unsettling question is this: with all our modern machines, would we still have the patience and collective focus to build something that takes generations to finish, knowing we’ll never see the final stone set in place?