On a crowded reef, small problems can become big emergencies: parasites sap energy, open wounds invite infection, and a bad reputation can get you chased off your own rock. Into this drama steps a tiny professional with a giant promise. Cleaner shrimp run bustling service stations where fish line up for a tune-up – parasites plucked, wounds tidied, stress soothed. Biologists once cast them as bit players compared with the famous cleaner wrasse, but new experiments and field surveys reveal a deeper story. These crustacean concierge teams don’t just groom fish; they help reefs function, one careful appointment at a time.

The Hidden Clues

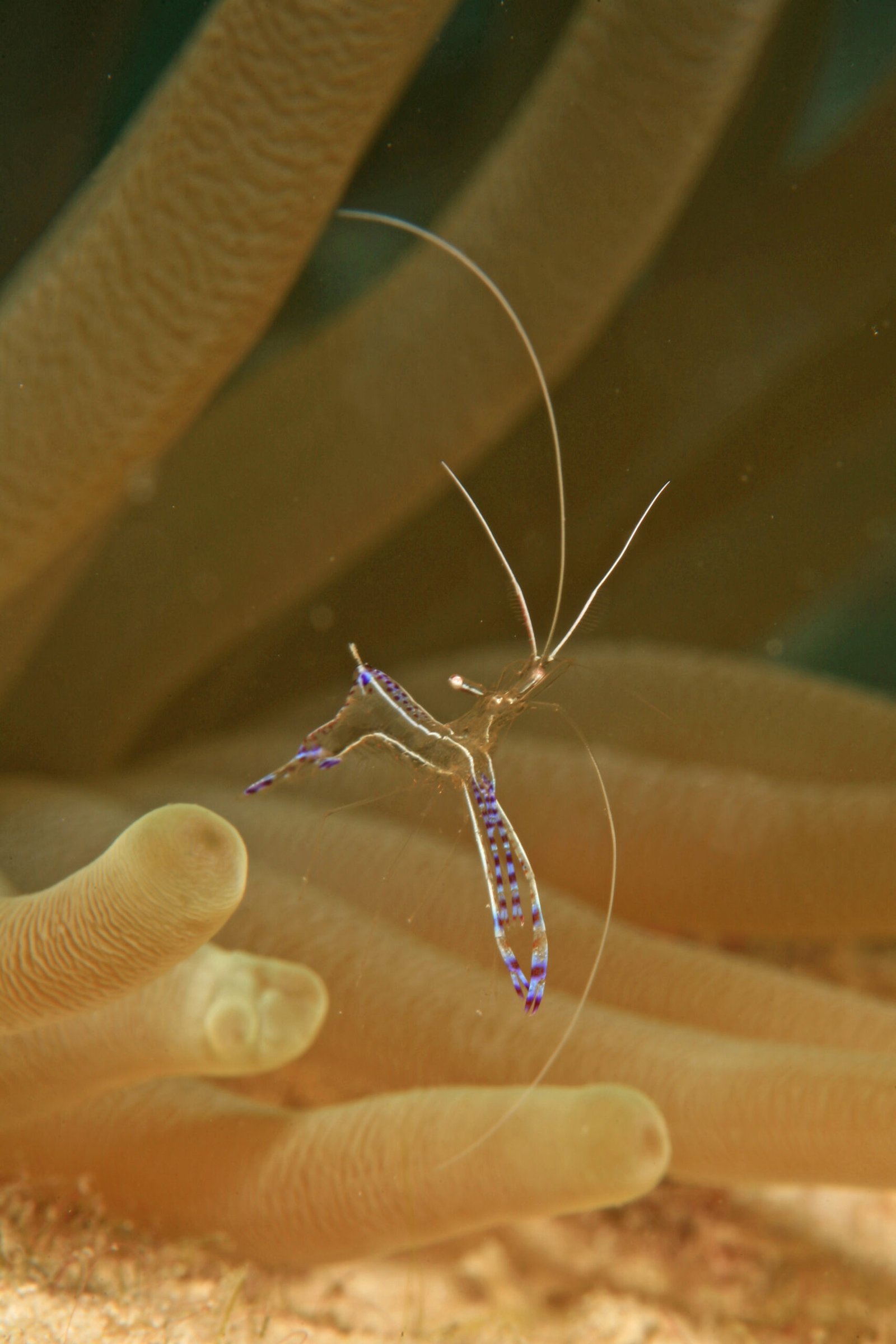

What if the best customer service rep on a coral reef is the size of your thumb? Cleaner shrimp advertise with a conspicuous rocking dance and waving antennae, a visual signal that says the station is open. Fish clients respond by striking a classic pose: fins flared, mouth parted, gill covers ajar, offering up delicate spots that predators rarely see. The shrimp glide in and get to work, snipping parasites and dead tissue with precision that would make a jeweler jealous.

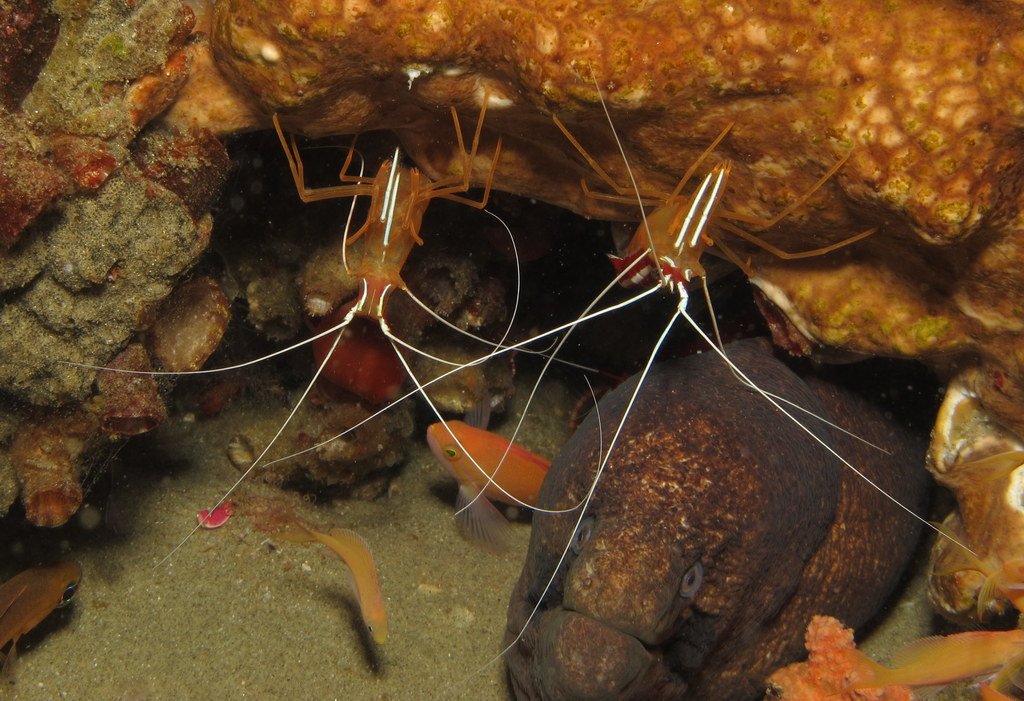

I still remember watching a pair of skunk cleaner shrimp on a night dive, lit by a narrow beam; a wary grouper hovered like someone waiting at a pharmacy counter. The shrimp tapped their client with delicate legs, a kind of tactile reassurance that reduced flinching and kept the session calm. The whole scene felt oddly familiar – like a busy repair shop where everyone knows the routine. Beneath the charm, though, is a high-stakes exchange where trust and timing keep the peace.

From Ancient Reefs to Modern Labs

Fossil-calibrated timelines and molecular studies suggest cleaner behaviors are not new fads; they likely evolved multiple times in shrimp lineages that include well-known species such as the Indo-Pacific skunk cleaner shrimp. On modern reefs, researchers map “cleaning stations” much like city planners map transit hubs, because fish return to the same sites day after day. In controlled trials, tanks with cleaner shrimp show lower parasite loads on resident fish compared with tanks without cleaners, and fish often heal faster from minor lesions.

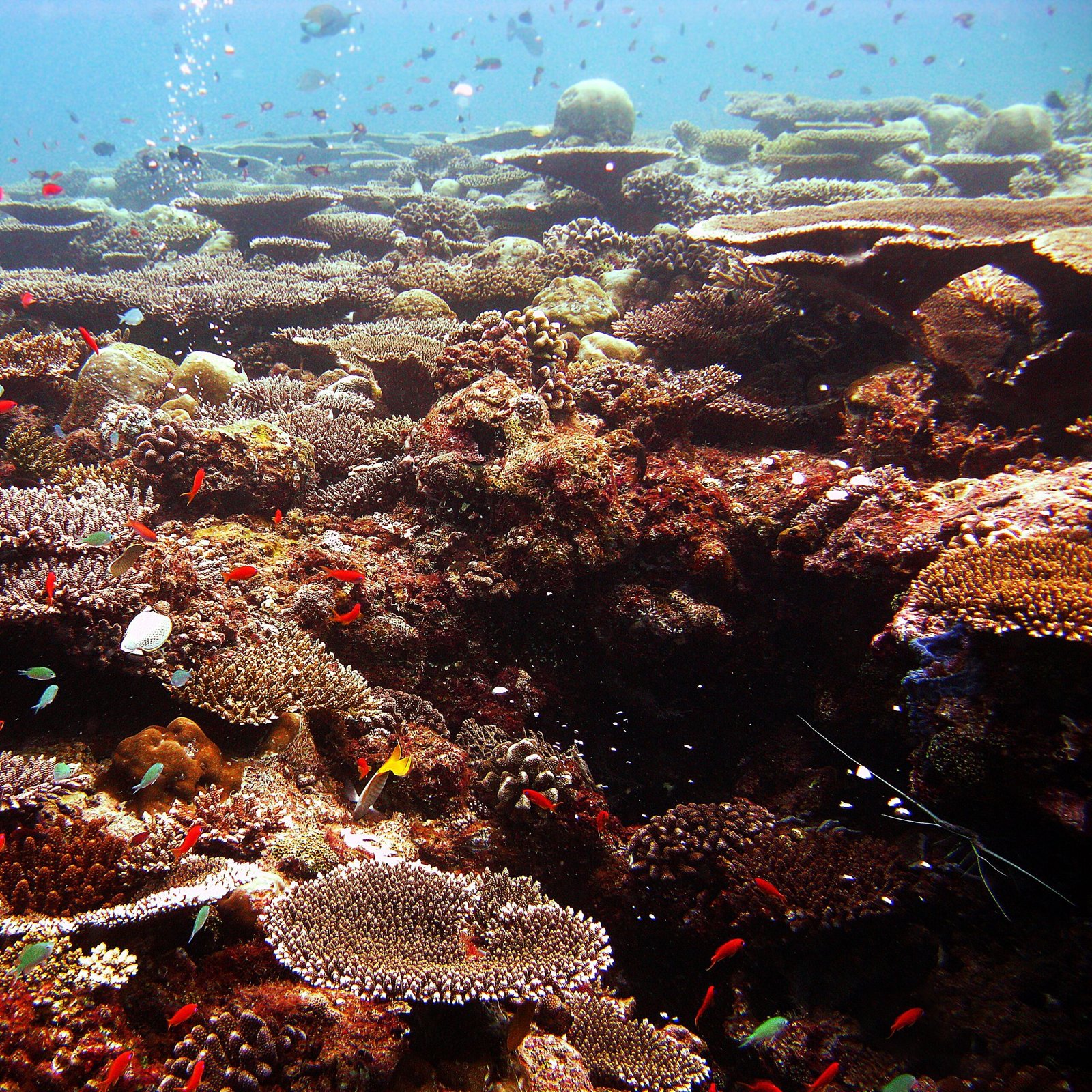

These lab insights echo patterns seen in the wild, where stations act like busy intersections drawing diverse clients: groupers, parrotfish, moray eels, even sea turtles on rare occasions. The repeat traffic suggests clients remember good service. When stations disappear, parasite communities shift, fish spend more time scratching on rocks, and stress behaviors spike. That feedback loop makes shrimp more than janitors; they’re quiet regulators of reef health.

The Dance of the Deal

Every appointment is a negotiation. Shrimp want nutritious parasites but are tempted by the easy calories of client mucus, which fish dislike losing. If a shrimp nibbles too much mucus, clients jolt or swim off, a live review that says the service crossed a line. Shrimp appear to anticipate this risk by offering gentle touches, a behavior that calms clients and earns a few extra seconds near sensitive areas.

Researchers track these interactions like economists track tipping behavior. Clients that receive quick, careful service return more often and tolerate longer sessions next time, creating a loyalty loop. Stations with reliable “staff” gain reputations that draw bigger, more valuable clients – think mega-grousers with lots of parasites to spare. Reputation, in other words, is currency on the reef.

The Economics of a Reef Service Industry

Mutualism is frequently described as a market, and cleaner shrimp run a remarkably fair one. There’s supply in the form of skilled labor and demand in the form of parasite-ridden clients. Price shows up as time in the chair: high-value clients receive longer, more careful service, while risky or fidgety clients get quick passes. Competition among stations pushes shrimp to signal more, dance more, and cheat less.

When predators approach, stations do not shutter; they negotiate. Large carnivores can be surprisingly gentle while being cleaned, presumably because the benefit outruns the cost of a quick snack. Over time, this uneasy truce converts potential conflict into commerce. The outcome is a web of small, repeatable successes that keep parasite pressure in check across a neighborhood of reef.

Why It Matters

For years, reef conservation has emphasized corals and charismatic fish, while the tiny service providers were treated as accessories. That view underestimates how strongly everyday maintenance can shape community health. By pruning parasite loads, reducers like cleaner shrimp help clients allocate energy to growth, reproduction, and migration rather than constant damage control. When parasites surge – after heat waves, storms, or pollution events – stations can act as buffers that slow the spiral toward disease outbreaks.

Compared with chemical treatments or manual fish handling in aquaculture, biological cleaning is gentler and often more targeted. Tanks that integrate cleaner organisms can reduce the need for repeated dosing and limit stress-related mortality. On wild reefs, keeping service stations intact may bolster fish resilience following bleaching, when stressed clients are extra vulnerable. In short, the smallest employees can stabilize the largest systems.

Global Perspectives

Cleaner shrimp occur in tropical and subtropical seas worldwide, from the Caribbean to the Indo-Pacific, yet their service model adapts to local conditions. In high-diversity hotspots, multiple cleaner species may share neighborhoods, each specializing on slightly different clients or microhabitats. On patchy or degraded reefs, stations become fewer and farther between, and client queues lengthen like a city with too few clinics. That scarcity can intensify competition and stress.

In aquaria and research facilities, shrimp already play frontline roles: they tidy small ectoparasites, groom delicate areas around gills, and lower visible irritation behaviors. Still, not every parasite is fair game, and not every fish tolerates service. The same ecological insight that guides reef management – protect the stations, match skills to needs – can guide smarter, more humane husbandry. It’s a reminder that solutions scaled from nature often travel well across borders.

From Stress Signals to Smart Design

Stress reduction may be the shrimp’s most underrated deliverable. Tactile stroking and predictable choreography decrease startle responses, which reduces the risk of injury when large clients hold still. Those repeated micro-calms add up to a safer neighborhood, like well-marked crosswalks on a busy street. Engineers and aquarists borrow that logic, designing habitats with clear “waiting areas,” escape routes, and refuge gaps that make service smoother for both parties.

Field biologists measure this with behavior metrics – jolts, flinches, session length – and physiological proxies like wound recovery and body condition. The pattern is consistent: where service is dependable, clients act less like prey and more like patients. In that shift lies a design principle that scales from reef alcoves to public aquariums: predictability lowers conflict. Good service, it turns out, is an architecture as well as an action.

The Future Landscape

Looking ahead, three questions loom. First, how will ocean warming and acidification alter parasite communities and client behavior, especially when heat-stressed fish queue for help? Second, can we responsibly scale cleaner shrimp roles in aquaculture without turning them into expendable tools? Third, what does station recovery look like after cyclone damage or coral loss, and how can restoration teams seed new service hubs?

Emerging technologies offer a path: high-resolution reef mapping to locate service bottlenecks, gentle eDNA sampling to track parasite dynamics, and small sensor arrays to log station traffic like a transit dashboard. Biologists are building agent-based models that treat shrimp and clients as decision-makers, forecasting how reputation, scarcity, and risk shape outcomes. Add careful breeding programs that maintain genetic diversity, and the field could move from ad hoc fixes to evidence-based deployment. The challenge is to scale the benefit without erasing the ethics.

How You Can Help

Support reef-friendly policies that curb runoff and sediment, because murky water disrupts the visual signals shrimp rely on. Choose aquacultured marine life over wild-caught when possible, reducing pressure on already-busy stations. If you keep a reef tank, research species compatibility and provide clear perches so cleaners can set up safe stations instead of hiding. Small design choices make service possible.

Donate to organizations funding reef monitoring where cleaner activity is mapped along with coral cover, not as an afterthought. If you dive or snorkel, keep distance from stations and avoid flash photography at close range; the best service happens when clients feel anonymous. Talk about shrimp when you talk about reefs; stories change budgets as fast as petitions do. Next time you picture ocean resilience, will you remember the little hands that keep the big bodies going?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.