Picture this: You’re standing at the rim of what looks like an ordinary mountain peak, but when you peer over the edge, instead of seeing rocky slopes tumbling downward, you’re staring at a pristine lake sitting perfectly inside a massive bowl-shaped depression. It sounds like something from a fantasy novel, yet these geological marvels exist all around our planet.

These aren’t just random pockets of water that somehow found their way into mountains. They’re the result of some of Earth’s most spectacular and violent geological processes that can literally hollow out the insides of entire mountains. The science behind these hidden lakes is both fascinating and surprisingly straightforward once you understand the incredible forces at work.

The Violent Birth of Hollow Mountains

When you think about how these hollow mountains form, you need to imagine Earth’s most catastrophic volcanic events. The formation of a caldera is a rare event, occurring only a few times within a given window of 100 years. The caldera was created in a massive volcanic eruption between 6,000 and 8,000 years ago that led to the subsidence of Mount Mazama. About 12 cubic miles (50 km3) of rhyodacite was erupted in this event.

The process begins deep underground where massive chambers of molten rock accumulate over thousands of years. Magma chambers play a crucial role in the formation of calderas. A magma chamber is a large underground reservoir that stores molten rock, or magma, beneath a volcano. These underground reservoirs can be absolutely enormous, containing enough molten material to fill entire cities.

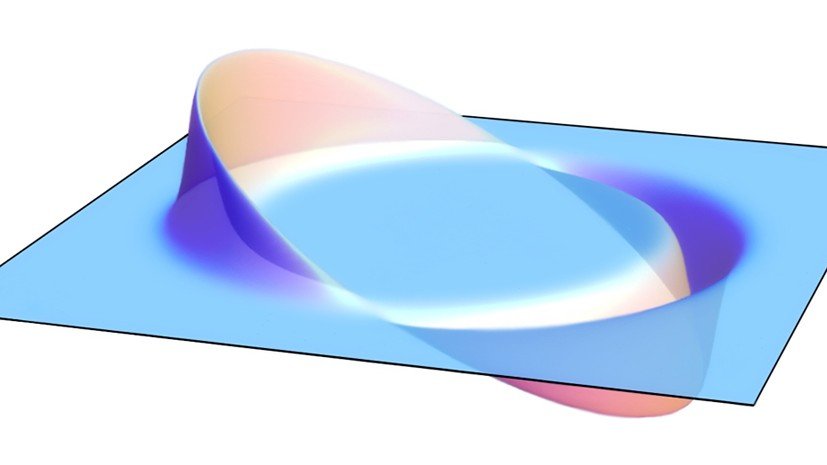

The magic happens during what scientists call a caldera-forming eruption. Crater Lake formed about 7700 years ago when a massive volcanic eruption of Mount Mazama emptied a large magma chamber below the mountain. The fractured rock above the magma chamber collapsed to produce a massive crater over six miles across. Think of it like removing the foundation from under a house, except the “house” is an entire mountain.

When Mountains Collapse Into Themselves

A caldera is a large, usually circular volcanic depression formed when magma is withdrawn or erupted from a shallow underground magma reservoir. The ground literally caves in on itself, creating these bowl-shaped depressions that can span many miles. The geological processes involved in creating a caldera after a volcanic eruption typically start with an explosive release of magma, leading to significant pressure decrease in the magma chamber. This pressure drop causes the ground above to collapse into the emptied chamber, forming a large depression.

What makes this even more remarkable is the scale we’re talking about. When Yellowstone Caldera last erupted some 650,000 years ago, it released about 1,000 km3 of material (as measured in dense rock equivalent (DRE)), covering a substantial part of North America in up to two metres of debris. That’s enough material to bury entire states under several feet of volcanic debris.

The collapse doesn’t happen all at once like a sinkhole. As more magma was erupted, cracks opened up around the summit, which began to collapse. Fountains of pumice and ash surrounded the collapsing summit, and pyroclastic flows raced down all sides of the volcano.

Nature’s Perfect Water Collectors

Once these massive depressions form, they become natural water collection basins. Crater lakes usually form through the accumulation of rain, snow and ice melt, and groundwater in volcanic craters. The steep walls of the caldera act like a giant funnel, directing precipitation toward the center where it has nowhere else to go.

No rivers flow into or out of the lake; the evaporation is compensated for by rain and snowfall at a rate such that the total amount of water is replaced every 150 years. This creates an incredibly pure water system because there’s no external contamination from rivers or streams. Due to several unique factors, mainly that the lake has no inlets or tributaries, the waters of Crater Lake are some of the purest in the world because of the absence of pollutants. Clarity readings from a Secchi disk have consistently been measured as being 120 ft (37 m), which is very clear for any natural body of water.

The filling process takes an incredibly long time. It is estimated that about 720 years was required to fill the lake to its present depth of 1,949 feet (594 m). Imagine waiting nearly eight centuries just to see a lake reach its full capacity!

The Science Behind the Perfect Bowl Shape

The reason these lakes fit so perfectly inside mountains isn’t coincidence. A volcanic crater can be of large dimensions and sometimes of great depth. During certain types of explosive eruptions, a volcano’s magma chamber may empty enough for an area above it to subside, forming a type of larger depression known as a caldera. The circular or oval shape comes from the way the collapse occurs uniformly around the edges of the emptied magma chamber.

One key feature is the large circular or oval depression that marks the caldera. This expansive feature often surpasses the size of craters due to its mode of formation. Calderas may also contain secondary volcanic structures such as cones, domes, or lava flows within the depression. These secondary features sometimes create islands within the lakes, adding to their mysterious beauty.

The walls of these depressions are incredibly steep and stable, which is why they can hold such massive amounts of water without the lake draining away. The volcanic rock that forms these walls is often very dense and impermeable, creating natural dam walls that can last for millions of years.

Famous Examples Around the World

A well-known crater lake, which bears the same name as the geological feature, is Crater Lake in Oregon. It is located in the caldera of Mount Mazama. It is the deepest lake in the United States with a depth of 594 m (1,949 ft). Standing at its rim feels like peering into another world entirely, with crystal-clear blue water stretching down further than you can imagine.

The largest known maars are found at Espenberg on the Seward Peninsula in northwest Alaska. These maars range in size from 4 to 8 km (2.5 to 5.0 mi) in diameter and a depth up to 300 m (980 ft). These Alaskan examples show just how varied these formations can be in different climates and geological settings.

You’ll find these hidden lakes on every continent except Antarctica. Maars occur in western North America, Patagonia in South America, the Eifel region of Germany (where they were originally described), and in other geologically young volcanic regions of Earth. Elsewhere in Europe, La Vestide du Pal, a maar in the Ardèche department of France, is easily visible from the ground or air.

The Underground Lake Mystery

Some of the most intriguing examples of lakes inside mountains are completely underground. Most naturally occurring underground lakes are found in areas of karst topography, where limestone or other soluble rock has been weathered away, leaving a cave where water can flow and accumulate. Natural underground lakes are an uncommon hydrogeological feature. These hidden water bodies exist in complete darkness, creating unique ecosystems.

The largest underground lake in the world is in Dragon’s Breath Cave in Namibia, with an area of almost 2 hectares (5 acres); the second largest is The Lost Sea, located inside Craighead Caverns in Tennessee, United States, with an area of 1.8 hectares (4.5 acres) These underground lakes form through completely different processes than volcanic crater lakes, but they’re equally fascinating.

Lakes form primarily under the force of gravity – water is pulled down to the lowest point in an area, and gathers into a lake. Any water below the water table will be under pressure, and so does not form a lake; instead, it forms an aquifer. The delicate balance required for underground lakes to exist makes them geological treasures.

Different Types of Mountain Lakes

A tarn (or corrie loch) is a mountain lake, pond or pool, formed in a cirque (or “corrie”) excavated by a glacier. A moraine may form a natural dam below a tarn. These glacial lakes represent another way mountains can hide water, though the formation process is completely different from volcanic crater lakes.

Commonly, alpine lakes are formed from current or previous glacial activity (called glacial lakes) but could also be formed from other geological processes such as damming of water due to volcanic lava flows or debris, volcanic crater collapse, or landslides. The variety of formation processes shows just how many different ways nature can create these mountain water features.

Tarns are the result of small glaciers called cirque glaciers. Tarns form from the melting of the cirque glacier. They may either be seasonal features as supraglacial lakes, or permanent features which form in the hollows left by cirques in formerly glaciated areas. These smaller lakes often appear like jewels scattered across mountain landscapes.

The Ongoing Mystery of Water Balance

One of the most fascinating aspects of these hidden lakes is how they maintain their water levels. Crater Lake is an anomaly among most mountainous lakes because there is no streamflow running into or out of the caldera. The water level of the lake is controlled by precipitation, evaporation, and seepage through surrounding rocks. It’s like a massive natural bathtub with no drain plug.

The present-day water levels are stabilized by a thick layer of porous deposits in the northeastern wall of the caldera, which acts as the “overflow drain” for Crater Lake. This natural overflow system prevents the lakes from spilling over their rims during heavy precipitation years.

The water chemistry in these isolated systems can be quite unique. Crater lakes can contain fresh water or be warm and highly acidic from hydrothermal fluids. Some crater lakes are so acidic they could dissolve metal, while others are perfectly drinkable. The difference depends on ongoing volcanic activity beneath the lake floor.

These geological marvels remind us that Earth is constantly reshaping itself in ways that can seem almost impossible. The next time you see a peaceful mountain lake, remember that you might be looking at the result of one of the most violent geological processes imaginable. These hollow mountains and their hidden lakes represent the incredible power of volcanic forces and the patient work of time and weather in creating some of our planet’s most breathtaking features.

What do you think about these natural wonders hidden inside mountains? Have you ever stood at the rim of a crater lake and marveled at the forces that created it?

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.