We grow up thinking of gravity as the simplest force in the universe: things fall down, planets go around the sun, end of story. Yet when you follow the evidence from black holes to the edges of the observable cosmos, that everyday picture falls apart in ways that are almost unsettling. Gravity, it turns out, is the one part of physics that stubbornly refuses to fit into our best theories of reality, and that tension is pushing scientists toward ideas that sound more like science fiction than high-school mechanics. This article explores the most radical shift: the possibility that gravity is not a fundamental force at all, but something that emerges from deeper, hidden ingredients of the universe. If that is true, then our familiar weight, the pull of the Earth, even the dance of galaxies might be side effects of something far stranger happening underneath.

From Apples to Space-Time: How Our Picture of Gravity Broke

For centuries, gravity seemed like the grown-up in the room: predictable, reliable, and mathematically tame. Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation worked so well that it guided ships, predicted eclipses, and even helped discover new planets. In that picture, gravity is simply a force acting at a distance, pulling masses toward each other like invisible strings. It felt intuitive in a comforting way: more mass, more pull; farther away, less pull.

Then came Albert Einstein in the early twentieth century and quietly upended the whole story. In general relativity, gravity is no longer a force but the bending of space and time themselves, like a heavy bowling ball warping a trampoline. Planets follow the curves in that fabric; they are not tugged along by any invisible hands. This geometric view explained strange observations, such as the way Mercury’s orbit shifts and how starlight bends around the sun, and it passed every test we could throw at it for decades. Yet the better we got at observing extreme places – neutron stars, black holes, the early universe – the more cracks began to show, especially when we tried to make gravity fit with quantum mechanics, our theory of the very small.

Quantum Fields Versus Curved Space: The Deep Mismatch

On one side of modern physics sits general relativity, which treats space-time as smooth and continuous, like a flexible sheet that can curve and ripple. On the other side sits quantum field theory, which describes particles and forces as excitations of underlying fields that obey the bizarre rules of probability, uncertainty, and entanglement. Each theory is incredibly successful in its own domain: relativity rules the cosmic, quantum theory rules the microscopic. But when you try to use them together – say, near the center of a black hole or at the beginning of the universe – they violently disagree.

Mathematically, combining them blows up in your face, giving nonsensical infinities where physical predictions should be. Conceptually, they talk about reality in totally different languages. General relativity treats gravity and geometry as inseparable, while quantum theory assumes a fixed space-time background in which fields live and interact. This mismatch is not a minor technical problem; it signals that our current description of gravity is incomplete at a basic level. For physicists, that is both frustrating and thrilling, because cracks like this are often where entirely new ideas emerge.

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: Gravity Behaving Suspiciously

If gravity were fully understood, the large-scale universe should behave in a tidy, predictable way given the matter and radiation we can see. Instead, when astronomers mapped the motions of stars in galaxies and the speeds of galaxies in clusters, they found something deeply unsettling: there is not nearly enough visible matter for gravity to hold these systems together. Stars in the outer regions orbit far faster than they should; whole clusters seem to be wrapped in an unseen gravitational cocoon. The simplest explanation is that an enormous amount of invisible “dark matter” is there, contributing mass and therefore gravitational pull.

As if that were not strange enough, measurements of distant supernovae and the cosmic microwave background revealed another twist: the expansion of the universe is speeding up, as if some mysterious “dark energy” is pushing everything apart. Together, dark matter and dark energy appear to make up the vast majority of the universe’s total energy budget, leaving ordinary atoms as a small minority. That means our everyday experience is shaped by the gravitational influence of stuff we cannot see and do not yet understand. It is hard not to wonder whether this is a clue that we have misunderstood gravity itself, instead of merely miscounting the contents of the cosmos.

Is Gravity an Illusion? The Radical Emergent View

In recent years, a growing number of physicists have entertained a provocative possibility: gravity might not be a fundamental force at all, but an emergent phenomenon. In this view, gravity would be more like temperature or pressure – collective effects that arise when you have many underlying microscopic degrees of freedom interacting. No single molecule “has” temperature; it only makes sense statistically, when you look at huge numbers of them. Similarly, perhaps no fundamental ingredient of the universe has gravity; it only appears when you look at how information, quantum states, or something even more abstract behave in large numbers.

This idea did not come out of nowhere. Hints emerged from studies of black hole thermodynamics, where black holes behave suspiciously like objects with entropy, temperature, and information content tied to the area of their event horizons. Some theoretical models suggest that the equations of general relativity can be derived from assumptions about entropy and information rather than taken as starting points. If that is right, then space-time curvature – and the “force” we feel as gravity – could be side effects of how underlying quantum information is organized. It is a dizzying shift: in this picture, gravity is more a story about bookkeeping of information than about masses pulling on each other.

Holograms, Black Holes, and the Edge-of-Reality Picture

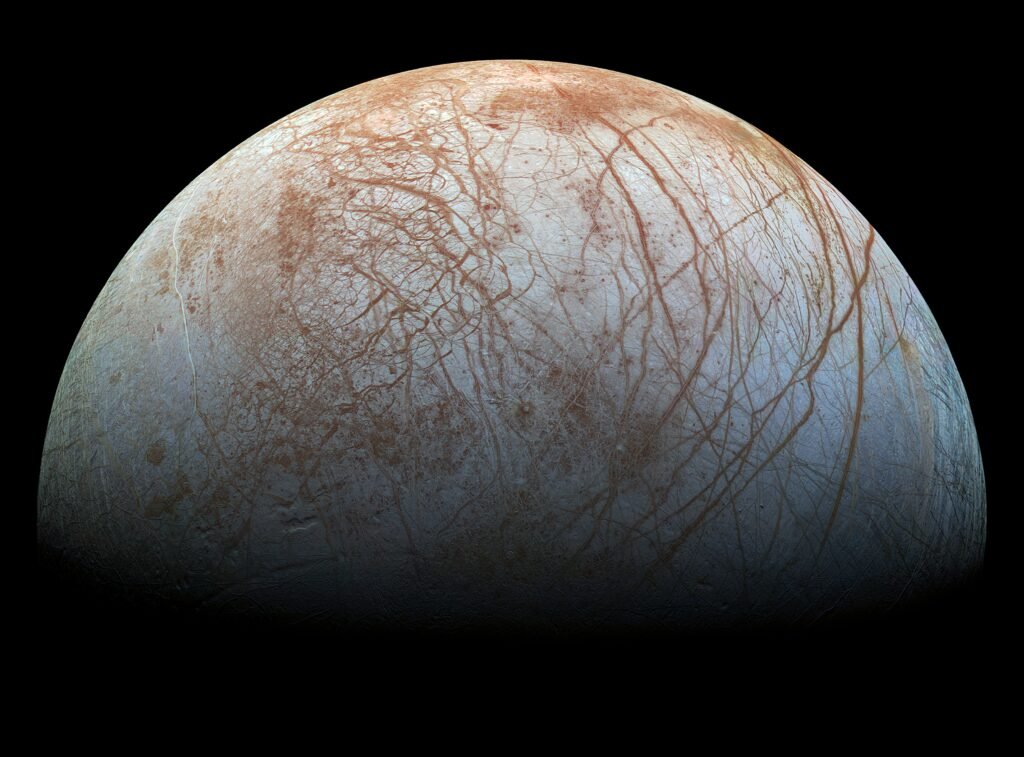

One of the strangest developments feeding this emergent gravity idea is the holographic principle. It suggests that all the information needed to describe a region of space, including its gravitational dynamics, could be encoded on a lower-dimensional boundary surrounding it, a bit like how a two-dimensional hologram can produce a three-dimensional image. Certain models in string theory made this more concrete by showing a precise mathematical link between a gravity theory in a higher-dimensional space and a quantum field theory without gravity on its boundary.

Black holes play a starring role here because their entropy seems to scale with the area of their event horizons, not their volume, which is exactly the kind of behavior you would expect if the fundamental information lives on a boundary. This area-scaling has pushed many researchers to think of space-time itself as arising from patterns of entanglement and information stored in some deeper structure. In that case, the curves and warps we interpret as gravity would be like the visual illusion created when countless pixels on a screen light up in just the right way. The objects falling, the orbits, even the black holes might all be emergent features of a holographic information game being played at the universe’s edges.

Beyond Textbook Gravity: What the New Paradigm Changes

If gravity is emergent, the universe looks less like a stage built from continuous space-time and more like a complex system where geometry, forces, and even time itself are side effects. That would put gravity in the same conceptual category as fluid dynamics: incredibly useful at large scales, but not the true story at the smallest scales. Just as water waves cannot tell you directly about the structure of individual water molecules, Einstein’s equations might be powerful approximations that gloss over the quantum details that matter most in extreme conditions. This perspective also reshapes what we mean by “fundamental law,” shifting attention from smooth geometric equations to rules governing information and entanglement.

Practically, it could change how we think about problems that have haunted physics for decades, such as what happens to information that falls into a black hole. If space-time and gravity are built from quantum information in the first place, then the “loss” of information might look very different than it does in a classical geometric picture. It also reframes the cosmological puzzles of dark energy and the universe’s accelerated expansion as questions about the large-scale behavior of the underlying microscopic degrees of freedom. Instead of patching gravity with new particles in the dark, we might need to rethink what gravity actually is.

Unfinished Business: Tests, Tensions, and Open Questions

For all its appeal, emergent gravity is not a settled theory, and many proposed models struggle when confronted with precise astronomical observations. Attempts to explain galaxy rotation curves or cosmic expansion without dark matter or dark energy have often run into trouble matching the full range of data, from gravitational lensing to the cosmic microwave background. In some cases, the models reproduce part of the behavior but fail elsewhere, reminding researchers that clever ideas still have to survive the brutal honesty of measurement. That tension is healthy; it forces theorists to refine their assumptions and drop the versions that do not work.

Meanwhile, more traditional explanations that keep gravity fundamental but add dark matter particles or a cosmological constant remain consistent with a huge amount of evidence. Experiments on Earth and in space continue to search for signals of dark matter, gravitational waves from exotic events, and tiny deviations from general relativity. Any confirmed anomaly could tip the scales toward or away from emergent gravity scenarios. Until then, the field lives in a state of creative uncertainty: bold ideas jostling with established frameworks, with the universe as the final judge.

Why This Strange Gravity Matters for All of Us

It might be tempting to file emergent gravity away as an esoteric argument about equations far removed from daily life. But how we understand gravity shapes some of the biggest practical and philosophical questions we face, from the ultimate fate of the universe to the limits of technology. Our navigation systems, climate models, and space missions already rely on Einstein’s refinements to Newton; future advances in understanding gravity could influence everything from gravitational wave astronomy to how we interpret signals from the early universe. On a deeper level, the idea that gravity might emerge from information forces us to reconsider what we mean by reality itself.

There is also a human side to this story that I find oddly moving. The same invisible pull that keeps your feet on the ground may be a faint echo of quantum entanglement patterns spread across the cosmos. The mundane sensation of weight could be a daily reminder that we are embedded in a universe whose true workings are vastly more intricate than our instincts suggest. That gap between what we feel and what the equations hint at is where curiosity lives. And in a sense, our refusal to accept the simple picture, our insistence on digging deeper even when the answers get stranger, is its own kind of gravitational force, pulling us toward a more honest understanding of the world.

Turning Curiosity Into Action: How to Follow the Trail of Gravity

Engaging with these ideas does not require a blackboard full of equations; it starts with paying attention to the questions that make you uneasy. Why does the universe expand the way it does? What really happens at a black hole’s edge? Instead of settling for the first simple explanation, you can treat those questions the way a good detective treats conflicting clues: as invitations to look closer. Popular science books, reputable online lectures, and open-access courses from universities can give you a front-row seat to the debate without drowning you in technicalities.

You can also support the institutions that are pushing our knowledge of gravity forward, from space observatories to ground-based gravitational wave detectors and public planetariums. When you vote, donate, or talk with friends and family about science funding, you are quietly influencing how boldly we can test these wild ideas about reality. Even something as simple as sharing a clear, accurate explanation of dark matter or black holes can help counter the noise of misinformation. In a world where gravity might be an emergent illusion, your curiosity is completely real – and it is one of the few forces that reliably pulls science into new territory.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.