If you grew up thinking gravity was a done deal – an apple falls, planets orbit, Einstein explains it all – the last decade of physics has a very rude surprise for you. The more precisely we measure the universe, from galaxies swirling in deep space to tiny particles in underground labs, the less gravity seems to behave like the clean, elegant force we see in textbooks.

In 2026, gravity is starting to look less like a solved puzzle and more like the corner piece of a gigantic cosmic jigsaw that’s still missing half the box. New theories are popping up, bold ideas are back on the table, and even some of the most respected physicists admit that something big might be wrong, or at least incomplete, in our current picture. If you’ve ever wanted to watch science in the middle of a plot twist, this is that moment.

We Still Don’t Know What Gravity Really Is

It sounds almost ridiculous, but it’s true: we can calculate how gravity works with breathtaking precision, yet we still don’t actually know what it is at the deepest level. Isaac Newton gave us equations describing how objects attract each other, but he never claimed to know why that attraction exists. Centuries later, Albert Einstein rewrote gravity as the curvature of spacetime itself, like a heavy bowling ball warping a trampoline, and that picture still underpins modern physics and GPS satellites today.

But when we zoom in to the insanely tiny world of quantum mechanics, where particles flicker in and out of existence and probabilities rule, Einstein’s smooth picture of spacetime starts to clash with everything else we know. Every other force in nature – electromagnetism, the strong force, the weak force – has a quantum description using particles like photons or gluons. Gravity is the odd one out, the stubborn rebel that refuses to fit into the same mathematical framework. That mismatch is a huge warning sign that our understanding is incomplete.

Dark Matter and Dark Energy: Gravity’s Biggest Red Flags

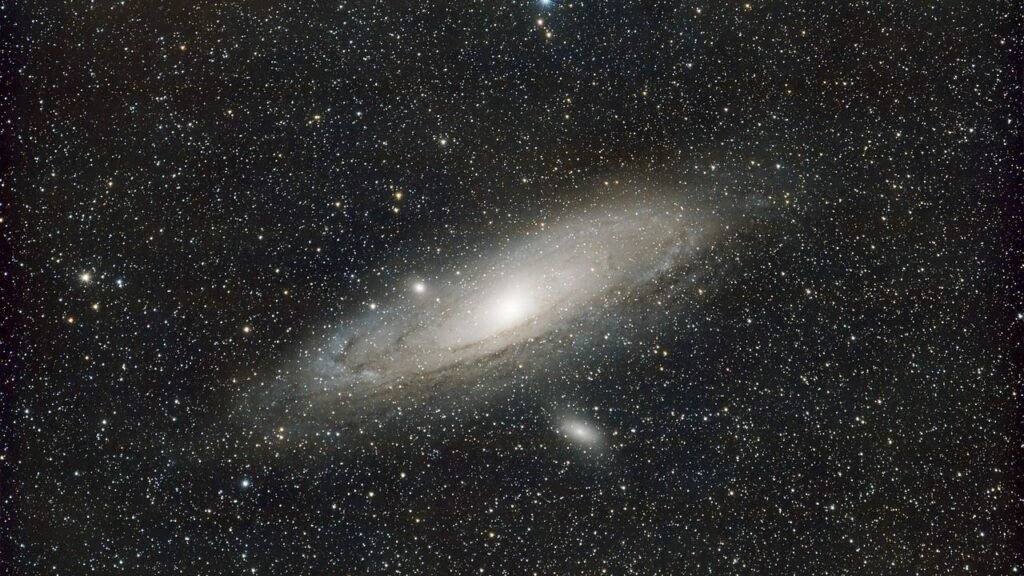

When astronomers mapped how stars move inside galaxies, they discovered something shocking: the visible matter we can see is nowhere near enough to explain the gravitational pull holding those galaxies together. Stars were orbiting so fast that, by all rights, they should have been flung out into space like mud from a spinning tire. To explain this, scientists proposed dark matter – some kind of invisible substance that exerts gravity but doesn’t emit light or interact with normal matter in familiar ways.

On even larger scales, observations of distant exploding stars suggested that the universe is not just expanding but actually speeding up in its expansion. That result shattered expectations and forced physicists to add another invisible ingredient: dark energy, a mysterious something that seems to push space itself apart. Put together, dark matter and dark energy now account for the vast majority of the universe’s total “stuff” in modern models. In other words, our best theory of gravity only works cleanly if we assume that most of the cosmos is made of things we’ve never actually seen directly.

Modified Gravity: What If Einstein Isn’t the Full Story?

Some researchers look at dark matter and dark energy and feel deeply uneasy. Instead of saying, “Let’s add invisible ingredients until the equations work,” they ask a more radical question: what if our equations for gravity itself are wrong on very large scales? This idea has led to a family of theories known as modified gravity, where the familiar laws we test in the solar system slowly change when you get out to galactic or cosmological distances.

One example is called MOND, short for Modified Newtonian Dynamics, which tweaks how gravity behaves when accelerations are extremely tiny, like in the outskirts of galaxies. There are also more complex frameworks, like scalar-tensor theories and f(R) gravity, that adjust Einstein’s equations in subtle ways. Some of these models can reproduce galaxy rotation curves without needing dark matter at all, which is both intriguing and controversial. The catch is that they have to survive a brutal battery of tests, from gravitational waves to precise measurements of light bending, and many proposed versions have already been ruled out.

Quantum Gravity: The Quest to Merge the Big and the Small

The biggest theoretical prize in all of this is a fully consistent theory of quantum gravity – a framework that explains gravity and quantum mechanics under the same roof. Two of the most famous approaches are string theory and loop quantum gravity. String theory imagines that fundamental particles are not tiny points, but minuscule vibrating strings, and that gravity emerges naturally from certain vibrations. Loop quantum gravity, on the other hand, suggests that spacetime itself is made of discrete, tiny chunks, like a cosmic 3D mesh.

Both approaches try to cure the mathematical breakdown that happens when we push Einstein’s theory into extreme conditions, such as the centers of black holes or the very first instants after the Big Bang. Some versions of quantum gravity hint that spacetime might have a smallest possible length, that singularities might be replaced by bounces, or that black holes could leave behind quantum remnants instead of swallowing information forever. The problem is that these ideas live at energy scales far beyond what we can reach in today’s particle accelerators, so testing them directly is brutally hard.

Holographic Gravity: The Universe as a Cosmic Projection

One of the strangest ideas to come out of quantum gravity research is the holographic principle. It suggests that the three-dimensional world we experience might be described by information living on a lower-dimensional boundary, a bit like how a 3D movie is encoded on a flat screen. In some carefully studied models, a theory including gravity in a volume of space can be mathematically equivalent to a gravity-free quantum theory living on the surface that surrounds it.

This holographic viewpoint has inspired fresh ways to think about black holes, information, and even the nature of spacetime itself. Some physicists now explore the idea that gravity could emerge from deeper layers of quantum entanglement, the ghostly connections between particles that Einstein himself once found unsettling. In that picture, spacetime geometry is not fundamental; it’s more like a pattern that appears when an enormous number of quantum bits organize in just the right way. It’s an unsettling thought: the world of solid objects and familiar distances could be more like a high-resolution illusion than the ultimate reality.

New Clues from Gravitational Waves and Precision Experiments

For most of history, gravity research was limited to watching how planets and stars moved and how objects fell on Earth. That changed dramatically when detectors first caught gravitational waves – tiny ripples in spacetime produced by colliding black holes and neutron stars. Since then, observatories have been steadily collecting more of these events, and each one offers a fresh chance to test Einstein’s theory in extreme conditions that were previously unreachable.

At the same time, ultra-sensitive experiments are probing gravity on very small scales, looking for any sign that it deviates from expectations. Some labs test how tiny masses attract each other at millimeter or even micron distances, while others try to measure how gravity affects quantum systems like ultra-cold atoms. So far, general relativity continues to pass these tests astonishingly well, but the measurements are getting more precise every year. The hope – or depending on your personality, the fear – is that eventually a small, consistent discrepancy will appear and point the way toward a deeper theory.

Simulations, AI, and the Next Wave of Gravitational Insights

As telescopes and detectors flood us with more data than ever before, from galaxy surveys to gravitational-wave catalogs, human intuition alone just can’t keep up. This is where large-scale simulations and artificial intelligence tools are beginning to play a serious role. Powerful supercomputers can now simulate how structures in the universe grow under different gravity theories, tracking billions of particles over cosmic time to see which models match reality best.

Machine learning systems are being trained to spot subtle patterns in lensing maps, galaxy distributions, and waveforms from distant mergers that might betray tiny cracks in our current understanding. That doesn’t mean AI will “solve” gravity on its own, but it can act like an insanely fast pattern-hatcher, flagging weird anomalies that humans might overlook. In a sense, we’re putting gravity on trial with ever more detailed evidence, and our models have to argue their case against a jury of cold, hard data.

Why Gravity’s Mystery Matters for the Rest of Us

It’s tempting to think of all this as abstract, ivory-tower stuff, far removed from everyday life, but I don’t see it that way at all. We already live in a world shaped by previous breakthroughs in understanding gravity and spacetime: GPS navigation, satellite communications, planetary missions, even basic timekeeping rely on general relativity being built into their systems. History suggests that when we dig into deep questions about nature, practical spinoffs eventually appear in ways no one predicts ahead of time.

There’s also something more personal in play: the story we tell ourselves about what kind of universe we live in. Are we in a cosmos where matter and gravity are fundamental, or one where information and quantum entanglement write the script and geometry is a side effect? Are we close to a grand unifying picture, or just scratching the surface of something far stranger? The fact that gravity, this everyday force that keeps your feet on the floor, still hides so many secrets is both humbling and thrilling. How could you not be curious about what we’ll discover next?